I have written about art for 23 years, longer if you count reviews in my college’s paper. I have spent a lot of time with a lot of artworks, and I thought I was pretty good at looking at art. But there is a whole other level to looking, which is seeing a work’s arc from blank canvas (or paper) to finished product. For this, you have to know how the artist did it. This semester I took my first art class since high school, and my first serious art class ever. And I have started to see art differently. I have begun to understand the mark-making, to recognize the physicality of getting certain results out of certain materials. And I’m not exaggerating when I say it’s almost as if long-dead artists were making their works before my eyes.

This came about because, a few years ago, the artist Seth Alverson told me I should take a painting class. I think Seth was a little appalled by my lack of art instruction, and he told me that a painting class would probably not turn me into a painter, but it would definitely make me better at looking at paintings. Which would make me a better art critic.

Prodded by Seth, I called the artist Francesca Fuchs, the head of painting at the Glassell School at the MFAH here in Houston. Francesca agreed that an art class would be good for me, but she said I couldn’t take painting until I took drawing.

Drawing: of course! I hear it’s fallen on hard times in some art schools, taught unsystematically by grad students who themselves were taught unsystematically by grad students. But all the artists I really respect take drawing seriously, regardless of the kind of work they make (even those who work with computers or do performance art). My late husband, the artist Michael Galbreth, said, “Drawing is an anchor, not a crutch.” I think he was responding to a dismissive attitude of some artists enamored with new technologies and convinced by the 20th-century idea that the artist’s “hand” no longer matters. But drawing is an anchor. It’s every cave painting, every great old painter mapping out their masterpieces, every sculptor envisioning a work, every installation artist conceptualizing the volume of a space, and yes, even every Photoshop artwork, as David Hockney’s surprisingly good iPad drawings show us (though ironically they must be seen in person, printed out, to be appreciated — I don’t think they work as well on a screen).

Drawing is understanding at the deepest level how everything looks, moment by moment. The world, to the eye, to the hand, to the paper — an unspeakably difficult and, done well, miraculous translation. As long as humans are still physical beings and not yet thought-clouds floating around the universe, drawing will matter.

This is how I ended up taking Drawing 1 this semester at Glassell. My instructor was Michael Bise, an artist who exclusively makes very good drawings. Michael is the kind of instructor you want: he knows his stuff and he’s not going to hold your hand, but he will be kind if he sees sincere effort, and will reward it with encouragement and detailed notes. He’s the kind of teacher you want to do well for, even when your (my) lack of raw talent is plainly evident.

Michael Bise giving a demo in drawing class

In Beginning Drawing we learned the basics: contour (the outline of shapes), negative space, shading, perspective. We mostly used graphite and charcoal, though we dabbled in ink one day. We had a couple of life drawing sessions (one male, one female), which is fun and funny and oddly sexless — you get over the novelty of looking at a live naked human quickly when you’re struggling to get the hands right. So far I’ve made one drawing that’s OK, although nothing I’d get excited about if I were to see it in a gallery. Much more importantly, I have experienced sinking into a drawing — losing sense of time as a desire to capture the world realistically takes over, concentrating on the mark-making to get it just right. And being humbled by the lackluster results of my efforts.

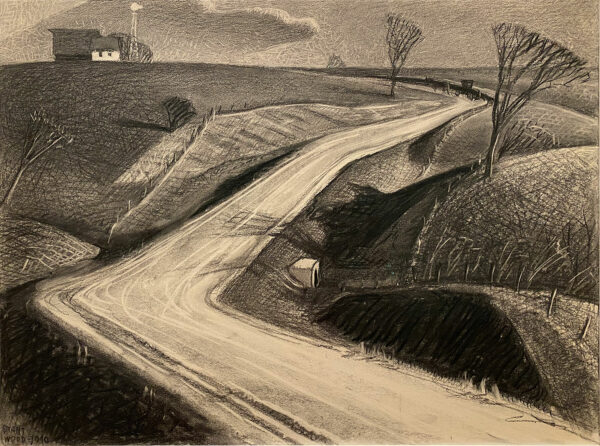

This semester I had the opportunity to test whether I’d gotten better at looking when the MFAH opened its new Kinder Building, which houses its permanent modern and contemporary collections. In the works on paper gallery, I was struck by this remarkable charcoal drawing from 1940 by Grant Wood, titled March:

Grant Wood, March, 1940, charcoal on wove paper

I first saw the drawing before the class started, and I’ve been back since several times to look at it more. I initially admired it because it’s vigorous and confident and such a great composition — that road! Those hills! It wasn’t until about halfway through the semester that I suddenly recognized the little bush next to the fence for the mere squiggle it is. It’s just a doo-dad! How long did it take Wood to place that bush — one second? Two at the most? And yet, despite its economy, it reads.

Before taking the class, I wouldn’t have consciously recognized that Wood made the dramatic, angular road by erasing over a ground of light color—those are the white stripes, which are energy and movement, as well as the sense of an uneven, rutted surface.

One of my favorite moments is the tree shadow that falls over the road. I love how Wood put down the pieces of it — darker lines on the right that bend up at the tips, indicating a raised edge in the road, and the lighter, brushier lines of shadow across the road itself, which Wood has erased through to reinforce the sense of the road’s texture.

The eraser does the heavy lifting again in the lower right, with the tufts of weeds to the side of the road:

Finally, the technically brilliant shading of the hills is offset by the energetic hatch marks, some of which are drawn in, and some erased. Those hatch marks are critical. They give the drawing interest, they indicate that this is stylized and not meant to be an exact replica of nature, and they also keep things from getting too sappy (which a picture of a country road disappearing into a landscape could easily do):

All these gestures, these simple marks that you can learn in a beginner drawing class, combine to tell us everything we need to know. They form a cohesive image when you step back and look at the whole (which Bise encouraged us to do, often, at our easels in class). But even though Wood’s techniques have been somewhat demystified for me, I am every bit as impressed as I was before the class — even more so, because I recognize the deeper mystery of the drawing’s power, brought forth by the artist’s skillful use of those basic techniques.

And though I said I wanted to get better at looking, my appreciation for March has moved beyond the visual and become something physical. I have a bodily appreciation for this artwork, for having lifted my own arm to paper, for having dirtied my own fingertips and the edge of my own hand rubbing charcoal, trying to make something that looked like something. It is so hard to do what Wood does here, on this one modestly scaled drawing in a gallery packed with them, in a building stuffed with great works of art, in a city and a state and a world spilling over with them.

And now all I want to do is keep looking.

Recent Comments