Bria Lauren (b. 1993) is a transdisciplinary visual artist born and raised in Houston’s Third Ward. The South is a sacred and integral part of her work as a visual storyteller, auntie, photographer, community organizer, cultural worker, and queer Black woman utilizing hood feminism as a social practice to navigate intersectionality and community building as an act of resistance. Lauren’s work intersects Black feminist theory, hood relics, ancestral healing, vulnerability, and motherhood. She brings the past to the present using photography, archival research, writing, installation, and film, communicating the true essence of Black femmehood and one’s identity without censorship.

Lauren’s solo exhibition, Gold Was Made Fa’ Her, took place at Lawndale Art Center in 2021. She has participated in group shows including There Is Enough For Everyone at the Blaffer Art Museum (2020), FOTO ATX Exhibit at the George Washington Carver Museum (online, 2020), IKE Smart City in collaboration with the City of Houston (2022), and Allium at WomxnHouse Detroit (2022). She has participated in Eldorado Nights (2021) at Project Row Houses, where she curated Eye on Third Ward as an extension of her participation, and she has organized the Jack Yates Production Experience: A Visual Arts Workroom (2022-23). She has given talks at Rice University, the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and her work and profile have been featured in Forward Times, AfroPunk, Outsmart Magazine, CRWN Magazine, Voyage Houston, F Magazine, the Houston Chronicle, Gulf Coast Journal, Deep Red Press, It’s Nice That, and Houstonian Magazine.

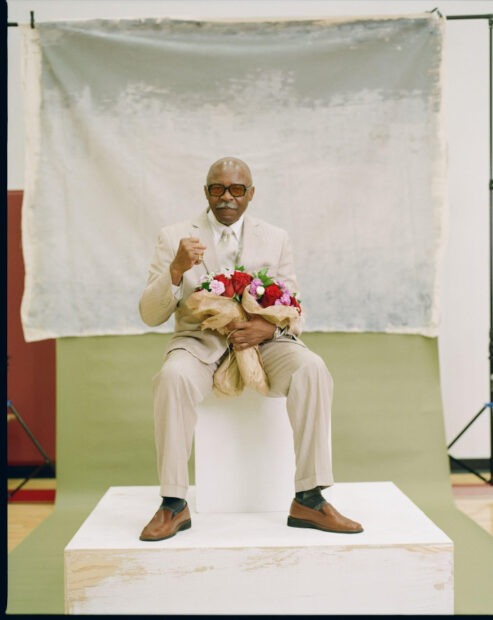

Installation view of “Bria Lauren: Gold Was Made Fa’ Her” at the Lawndale Art Center, 2021, photo courtesy of the artist

Liz Kim (LK): Would you tell us about your ongoing series and project, Gold Was Made Fa’ Her? How does it encompass your relationship to Houston?

Bria Lauren (BL): It’s interesting to be asked about Gold Was Made Fa’ Her from the lens of a photo series and project because, since the debut exhibition in 2021, it has become more of a movement and a hood manifesto for me. GWMFH is a love letter to the Black hood women I grew up with in Third Ward, Houston, and a love letter to my younger self, who was once ashamed of who she was and where she came from. The Southside of Houston is home — the foundation of who I am, and the why behind the start of my practice.

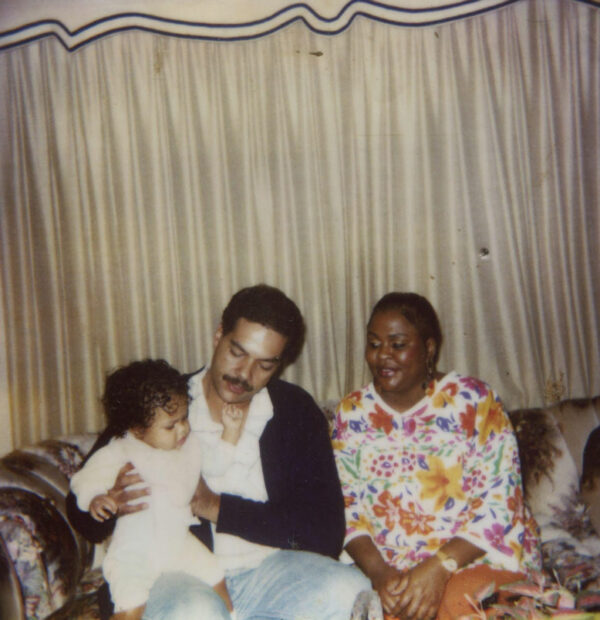

Family photograph: Rhonda’s baby Bria, with father, Lawrence Wideman, and mama, Rhonda Harrison-Davis, Houston, Texas, 1993, photo courtesy of the artist

When I decided I wanted to tell stories and take pictures, I came to Third Ward, because it was the only home I knew. I later discovered that my mama was always taking pictures, archiving our family’s history, and writing, since she was a young girl. In the same way that DJ Screw said he was going to screw the world, I want to plant roses everywhere for Black women through the work we do together. Gold Was Made Fa’ Her is an affirmation for Black women. No matter how the world may judge us, try to shrink, mimic, or change us, no matter what we go through, gold was still made for us. My mama wrote Gold Was Made Fa’ Her in her daily bread book next to the Acts 20:17-24 bible scripture: “I consider my life worth nothing to me; my only aim is to finish the race and complete the task the Lord Jesus has given me — the task of testifying to the good news of God’s grace.”

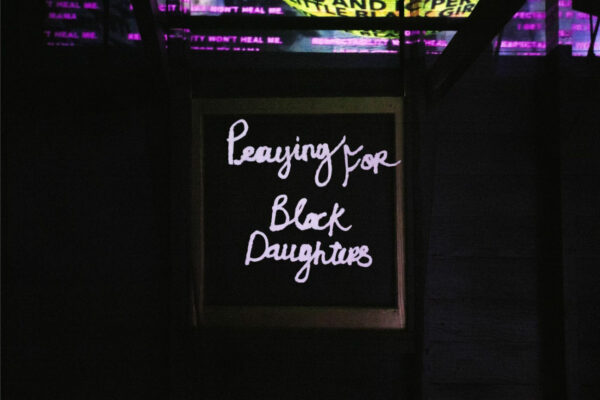

Installation view of “Bria Lauren: Gold Was Made Fa’ Her” at the Lawndale Art Center, 2021, photo courtesy of the artist

LK: What does Houston’s Black queer community and its history mean to you?

BL: My introduction to the Black queer scene in Houston was Club Big Yo’s in 2009, which most folks in the city know today as Tout Suite. Yo’s was a gay nightclub owned by Yolanda “Big Yo” Newmon. It was my first reference to a Black underground colorful universe where whether you were gay, trans, bi, in drag, or somewhere in between, there was space for you to be yourself. Historically, we’ve always had to build our worlds creatively, and it’s inspiring to have archives of Black gay women being the architects and leaders of worlds that have shaped our communities here down South. Shout out to Big Yo!

It’s cool that we’re having this conversation, because it feels like I’m coming out for the first time while expressing myself through writing these days. I get it from my mama, who was queer in her own right, and would only wear one earring, never two, and called it “of gender.” Since I was a young girl, I’ve always had a complex relationship with my sexuality and identity, but I told myself in 2024 that I would be more intentional about embodying the fullness of who I am, and making sure the spaces and visual stories I am connected to reflect that.

Eugene E. Harrison (far right) and friends, Houston, Texas, circa 1945-1950, photo courtesy of the artist

LK: How does your family history influence your practice?

BL: I come from a lineage of disrupters, innovators, artists, entrepreneurs, teachers, and leaders. My grandfather, Eugene Harrison, was inducted into the Texas Black Sports Hall of Fame in 2019 for integrating golf with three other friends, Lee Powell, Charles M. Washington, and Howard McCowen, on June 19, 1946, at Memorial Park. During this time it was illegal for African Americans to play on golf courses in Houston publicly.

On June 19, 2021, 75 years later, The Lone Star Golf Association celebrated the unveiling of the honorary plaque placed at Memorial Park Golf Course in the founders’ honor. Mayor Sylvester Turner proclaimed June 19, 2021, the Lone Star Golf Association Day.

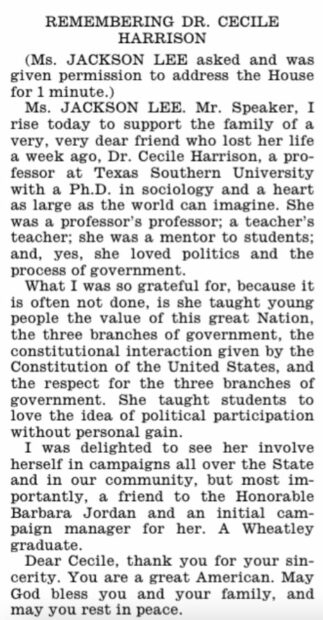

Congressional tribute to Lauren’s great aunt: “Remembering Dr. Cecile Harrison,” Congressional Record – HOUSE, VOL. 159 Pt.10 September 30, 2013

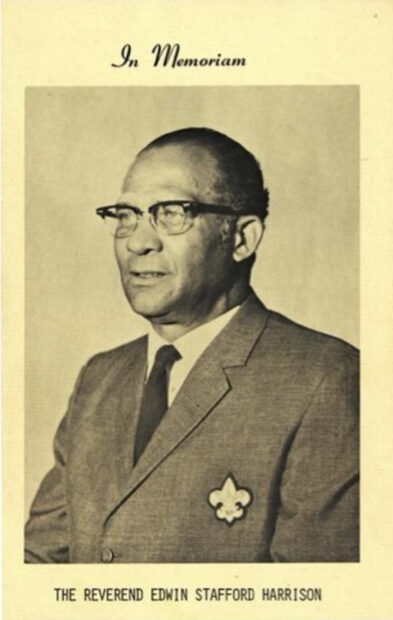

My great aunt, Cecile Harrison, was a sociology professor at Texas Southern University (TSU), community organizer, and openly gay feminist activist who worked closely with Barbara Jordan as her friend and colleague. My great uncle Rev. Edwin Stafford Harrison was a minister, Scout Executive of the Boy Scouts of America from 1944 to 1976, and the first Black precinct judge and poll tax writer for Harris County. Scouts Honor: Black Boy Scouts In Houston 1940’s- 1970’s was just on view at the Gregory School in 2022, featuring Uncle Edwin’s work with the Boy Scouts and highlights from the Harrison Family Collection.

My aunt Sandra Harrison, Rev. Edwin Harrison’s daughter and the oldest living Harrison, was a computer science and math teacher at Jack Yates, and it’s important to note that all late Harrisons were Jack Yates High School graduates. Aunt Sandra has shared memories with me of how it became a tradition for their house to be the house for fellowship and a nurturing space for children in their community. Mama talked highly of Uncle Lee Harrison, who was one of the first Black police officers in Houston. I come from “good stock,” as the old folk would say. My people were about that action, and stood ten toes down on everything they believed in, for Houston and Black people as a collective. It makes sense for my practice to pivot the way it did: pretty quickly beyond photography and into a social practice. There is a calling to continue the work and the legacy my family started. Although it is a heavy assignment, when I am lost and unsure of my path, it gives me something to believe in.

Installation view of “Scouts Honor: Black Boy Scouts In Houston 1940’s- 1970’s” at The African American History Research Center at the Gregory School, November 12, 2022 – January 28, 2023, photo courtesy of the artist

LK: How are you feeling these days, coming back from a major auto accident from October 19, 2022 that disrupted your life and career? Would you be open to sharing your experiences over the past year?

BL: Every day is different, and how I feel changes by the minute. I still have moments when it hits me like, damn, this really happened to me. But my goal these days is to try to shift my perspective, that the car accident didn’t happen to me, it happened for me. I am also human, so my body and reality will remind me that I am still in recovery and need help, and sometimes I don’t know how to navigate this. And because I don’t look like what I’ve been through, it is frustrating to feel like my story is old news. Most people don’t know just how bad the impact was. I can’t even count how many surgeries I’ve had in the past year. It is a miracle that I am alive and didn’t die.

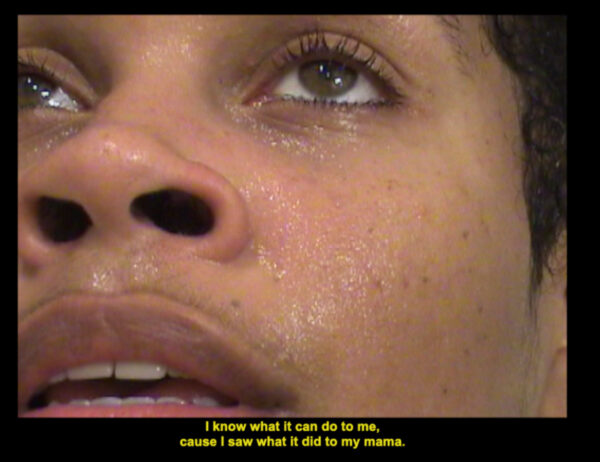

Installation view of Bria Lauren’s mixed media film installation “Rhonda’s Baby” at WomxnHouse Detroit, 2022, photo courtesy of the artist

I’m advocating for my medical debt forgiveness and learning how to get back on my feet, literally and figuratively. I’m still processing that Houston does not have medical emergency grants for artists, and if it wasn’t for community rallying for me online, I am not sure how I would have made it thus far. I know I am grateful for my life, and there is a reason I’m still here. The most challenging part has been feeling estranged from my art practice and being afraid that “if you don’t use it, you lose it.” But a friend and one of my favorite photographers, Eric Michael Ward, recently told me, “You don’t lose the gift because God gave you that.” Since the beginning of my recovery, people have often sent me videos and images of my work and myself in the IKE Smart City kiosks around Houston. Once, I was on my way to a doctor’s appointment and saw the portrait I took of my mama; seeing her smiling and looking at me felt like her telling me, “It’s gonna be alright, Frenchie.” I am so blessed, I am loved, and I am grateful.

Installation view of Bria Lauren’s mixed media film installation “Rhonda’s Baby” at WomxnHouse Detroit, 2022, photo courtesy of the artist

LK: Why is it important for you to bring photographic production experience to Jack Yates High School through the Jack Yates Production Experience: A Visual Arts Workroom, and how has Ray Carrington’s legacy at Jack Yates and beyond impacted your work?

BL: The Southside of Houston has been the focus landscape of my work, and after the debut of Gold Was Made Fa’ Her, I began asking myself what Black women and our community need beyond being seen. The more I cared for my mother during the most vulnerable stage of her life, the more I felt responsible for organizing spaces and creating opportunities for a community that cared for me as a child. Jack Yates High School fed, provided, and guided me throughout my high school years. I was always different, but the harsh reality is there aren’t enough spaces and resources for neurodivergent and creatively inclined children in Black communities. I stand on the shoulders of Mrs. Ratliff, Uncle Dooley, Mr. Carey, and Ms. Clayton.

Mr. Ray Carrington lll was the photography teacher for nearly 30 years at Jack Yates High School. I knew he was tired, and I wanted him to see that the younger generation could hold things down for him and keep the spirit of his presence and offerings alive. It is time for us to remember Mr. Carrington’s contributions, and especially Eye on Third Ward‘s legacy in and outside the photography classroom. [Editor’s note: The annual exhibition of Jack Yates High School photography students at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, initiated by Mr. Ray Carrington, saw its 28th iteration in 2023 as Eye on Houston.]

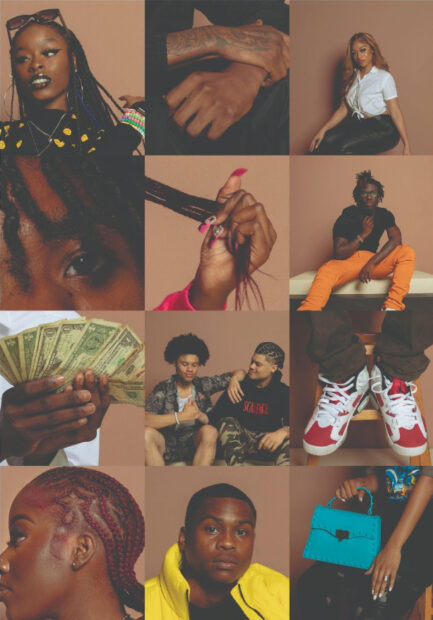

Jack Yates Production Experience: A Visual Art Workroom was founded by Gold Was Made Fa’ Her and launched in 2022. The JYPE is an immersive teaching experience that nurtures and exposes the students of Jack Yates to infinite possibilities of the arts and creative industry. The purpose of this experience is to empower the youth of the Third Ward community to imagine their creativity as an incubator for their success, and to take ownership of their skills and personal narrative. It takes a sustained village to continue the work of art pioneers, historians, photographers, mentors, and teachers like Mr. Carrington. It matters for me to commit to being a part of this village. Nina Simone said, “It is an artist’s responsibility to reflect the times.” And I hold that belief in my heart. I would love to see the Worthing High School Production Experience, the Cullen Middle School Production Experience, etc. I see this expanding into a creative curriculum for the Southside of Houston and beyond.

I give thanks to Kindred Stories, the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Houston In Action, See A Need. Meet A Need., Mo Betta’ Brew, Wonderful Beginnings Learning Center, CoolxDad, Jasmine Williams, DJ Elevated, Morganne Nikole, Danielle Mason, Troy Ezequiel, Ann LeCompte, Eric Michael Ward, Melanee Brown, Bee Honey, Edgar Mendoza, David Landry, Jamey Watts, Jack Yates High School, and the many talented artists and collaborators in the city who have pulled up to make this work possible.

LK: How did your series Gold Was Made Fa’ Her lead up to Rhonda’s Baby (2022), which was shown late last year at WomxnHouse Detroit as a part of your artist’s residency there?

BL: My heart cries when I talk about Rhonda’s Baby, and I appreciate you asking me about it. I dedicated the Gold Was Made Fa’ Her exhibition to my mama and elevated her importance throughout my life because we both needed it. In celebrating other Black women from Third Ward, adoring my Mama and acknowledging her sacrifices felt like a calling from spirit. 2021 was the first time I included her in my work and invited her to share space with me as my mother. After she transitioned on July 19, 2022, I needed to create something tangible to release what I was holding onto, and to turn the camera to myself. I needed to hear and see my truth without looking for anyone to validate it. I needed somewhere to place my grief.

Rhonda’s Baby is a portrait film and audible diary telling the highs and lows of surrendering to being undone and to a state of disembodiment. I am standing at the crossroads and wading through water in search of myself — while being confronted by my past, my mama, childlike dependence, internal shadows, and the will to transcend. This work stretched me — created a space for me to be experimental in my practice, and to meet me where I was. I am forever grateful to WomxnHouse Detroit, Laura and Rich Earle, my father Lawrence Ellis Wideman, my Mimi Mildred Wideman, and my sister Angela Wideman for welcoming me home on Detroit’s West Side.

LK: What does a future with photography and your role in the arts look like?

BL: I’m in the process of figuring this out for myself, and I believe my only responsibility right now is to be clear with my intentions, desires, and faith, and to remember my life’s agreement. I remember years ago, not knowing how to load a roll of film into a camera, compose an image, or the difference between aperture and shutter speed. Fast forward to today, as I continue my recovery, I’m in a Photography 101 class. My peers are my teachers, and they’re helping me remember who I am.

It is a scary yet humbling position, but I hope to continue the balance of trusting and investing in the gifts I came here with, while remaining a student forever in being open to learning and trying. It helps to look at my work and accomplishments from the past, especially when I feel insecure and clouded with the fear of being forgotten or just not being “good.” I recently reflected on the day I led studio visits with MFA photography students at the University of Houston’s School of Art, Photo and Digital Media, in 2021. I’m still holding on tight to the words I wrote there two years ago: “Replace concept with story every time; having a strong sense of self keeps you rooted in why you make the work you do; the process of making an image is a conversation; always pay what you learn forward; and there is no such thing as a ‘good photographer.’ Keep learning, keep trying, and DO YOU.”

My intention for my role in the arts is not to be afraid of building my worlds, creating my own colorful universe, and going after whatever I want to see come to pass. There are stories I’ve yet to tell, spaces I’ve yet to curate, and work I’ve yet to do with Black women, so it feels good to have something to look forward to. I’m also excited to trust my visions more — if God says the same as my mama would say, beautiful breakthroughs are on the horizon for me, and Gold Was Made Fa’ Her.

Recent Comments