Bruce Hainley’s book Under the Sign of [sic] delves into the provocative practice of “copying” in art, highlighting how artists like Elaine Sturtevant used meticulous recreations of famous works to challenge modernist ideas of originality, authorship, and the art market’s obsession with the new. Sturtevant’s work wasn’t about simple duplication; it was a deeper critique of the art world’s fixation on novelty and authenticity. In this spirit, Caroline Gray’s latest exhibition, Stutter, at Front Gallery in Houston, engages with similar themes, transforming the act of copying into a thoughtful exploration of how viewers experience art in the digital age.

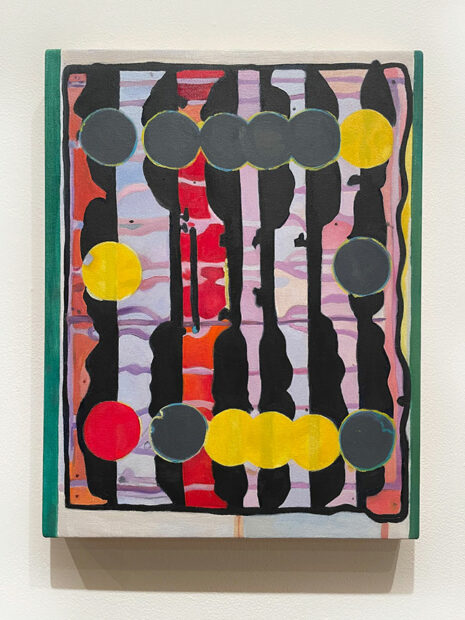

Gray uses digital images of another artist’s paintings, specifically the works of Matt Conners, as the basis for her own large and small scale pieces. This approach is more than imitation; it’s a means to explore deeper questions about originality, creativity, and how art is experienced today. Gray’s process starts online, where she finds photos of Conners’ paintings on his gallery’s website, then translates these digital images into hand-painted canvases. By doing this, she draws attention to how much of the modern art experience occurs on screens — through Instagram, websites, or digital catalogs — often stripping away the texture, scale, and presence that define viewing art in person.

This practice isn’t new in the art world. Sherrie Levine, for instance, became known for re-photographing iconic works by figures such as Walker Evans, notably in her series After Walker Evans (1981). By presenting Evans’s Depression-era photographs as her own, Levine challenges notions of originality and authorship, suggesting that all art is a reproduction of existing images and cultural narratives. Similarly, Richard Prince re-photographed advertisements to critique consumer culture, while Elaine Sturtevant meticulously recreated famous artworks to question the very concept of originality. Gray builds on this tradition but extends it into the digital age, where images are shared, reposted, and remixed so frequently that they lose their connection to any singular “original” source.

A compelling aspect of Stutter is how it turns copying into an intentional artistic gesture, much like using “[sic]” in writing to indicate a faithful reproduction of a source, mistakes and all. Her paintings are not just replicas — they explore how art’s meaning changes as it moves between different contexts, from the gallery space to the endless scroll of online feeds. This invites viewers to reflect on how artworks evolve in meaning across different platforms.

The idea of copying as a creative act extends beyond the visual arts. In literature, Jorge Luis Borges’ short story Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote explores a writer who recreates Cervantes’ Don Quixote word for word. Though Menard’s text is identical to the original, its meaning shifts entirely because it was written in a different era, by a different author. Borges’ story shows how the act of duplication can itself become a form of creation, challenging reader’s understanding of authorship and originality.

Gray’s Stutter operates in a similar vein. By painting digital images of Conners’ works, she examines how art transforms as it moves across different spaces — physical galleries, digital screens, and her own canvases. The exhibition becomes an exploration on how art can live multiple lives, where each iteration adds new layers of meaning, much like Borges’ literary investigation of duplication.

In the spirit of Bruce Hainley’s examination of Sturtevant’s work, Gray’s exhibition positions copying as a form of artistic inquiry rather than mere replication. By embracing reproduction, Stutter becomes a thoughtful reflection on how artworks are shared, reinterpreted, and transformed. Caroline Gray demonstrates that in a world flooded with digital images, the act of copying is not merely derivative; it’s a powerful way to question the authenticity of visual culture.

Recent Comments