By the time a booming baritone called for attention, approximately fifty people had gathered at Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino on West Alabama, flitting in and out of the main exhibition space to an excited buzz. We were there to attend the opening talk for artist Gustavo Díaz’s fourth solo show at the gallery. As we settled down on folding chairs and stools among the artworks, there was a discernible sense of anticipation. What would he be like, this man whose drawings many of us already admired?

The artist we met that day was soft-spoken and reticent to address us in English, an Argentinian who carried with him four volumes of Jorge Luis Borges’s collected works, talismans with which he’d arrived in Texas nearly ten years prior. Gustavo Díaz — 54, with salt and pepper hair tied back at the nape and a trimmed beard — had never given a public talk in English before. At one point, he said he felt the talk was “like a confession,” an earnest admission from someone who has kept a deliberately low profile in the art world even as important local collectors and national art museums have acquired his work. Díaz, who seemed earnestly embarrassed by the praise and rapt attention his audience bestowed, was at times candid and at others reserved; he was working out the fine line between private and public which he will undoubtedly have to tread into the future — because he is no minor artist, and ears are pricking up.

I. VECTORS

I remember the microscope most distinctly. I had arrived at the opening for Díaz’s first solo exhibition at Sicardi, back in 2018, and as soon as I stepped into the cool, familiar buzz of the gallery, I noticed the lab equipment. It was meticulously arranged inside a glass case, next to books about data visualization and fuzzy logic on one side and a set of surgical tweezers and forceps on the other. Lab flasks, Petri dishes, and what looked like flashcards of various histological samples fleshed out this rather odd still life for an art gallery. Next to the case hung one of Díaz’s intricate paper cut-outs, the color of sand: it looked like a minutely perforated cross-section of brain tissue. All I could see was a mass of cells surrounded by fiber tracts and fractal patterns. I had grown up around such images, usually stained pink or purple and printed on glossy posters from brain conferences my parents attended; none of them had ever struck me as art. This one attracted me immediately — I kept a printout pasted on my library carrel for years.

Gustavo Díaz, “Writings knotted like nests,” from the series: “Golden Writings,” 2024, cut out paper, 19 11/16 x 24 11/16 x 2 inches

Díaz’s cut-out monochrome drawings are nothing short of astounding. Anyone who has stood before them would be forgiven for thinking they were the product of a supercomputer and not a remarkably mild-mannered man. Working in sheets of 18” x 32”, he traces thousands of vectors on a computer screen to create a primary composition and then uses a laser cutter to etch away the negative space. Some excised pieces are so minute, that he uses tweezers to pick them out. He then arranges the sheets in a full composition, adding colored pencil for dimension. In their frames, the largest ones are massive — navigating them by sight feels like a hard lesson in topology. Contemplating the time it has taken to draw every line, make every cut, lift every chad is staggering. The man works 18 hours a day, “thirteen or fourteen when I’m tired.”

Throughout my conversations with and about Gustavo, I began picturing him as a modern-day monk, living a life of near-cloistered devotion to his art. He recently spent two years in New York, with his studio only a few blocks away from The Museum of Modern Art. He never visited. In Houston, where he lives with his family, “the only motivation to leave my house is going on a walk, to look for feathers.” He is astonishingly focused and seems energized by difficulty. One of the first personal stories he told me about himself is from when he had just arrived in the United States and didn’t speak the language. To teach himself, he bought a set of books about topics he had already studied in Spanish, reasoning that since he knew their content, he’d be able to deduce the meanings of English words as he read the texts, and in so doing, learn the language. The anecdote reminded me of 19th-century scholars deciphering the Rosetta Stone — in the age of Duolingo, the necessary patience and dedication of such a task struck me as outlandish, and at the same time, charmingly erudite. I liked him immediately.

II. GRAPHITE

The baritone in the gallery belonged to an interpreter, but he was called on very rarely — for all his bashfulness about a lack of fluency in English, Díaz hardly required mediation, reverting to Spanish only a handful of times, to translate single words. “I choose work that requires time,” he explained to the assembled crowd, hanging on his every word. Beside him, his interlocutor Rachel Federman nodded thoughtfully. A curator in New York, Federman developed a relationship with Gustavo through Edouard Kopp, Chief Curator at the Menil Drawing Institute. She visited him in his New York studio on several occasions to discuss his practice, a space she described to me as “overwhelming.” “I have seen the universe of Gustavo’s mind,” she told the audience archly, to polite laughter.

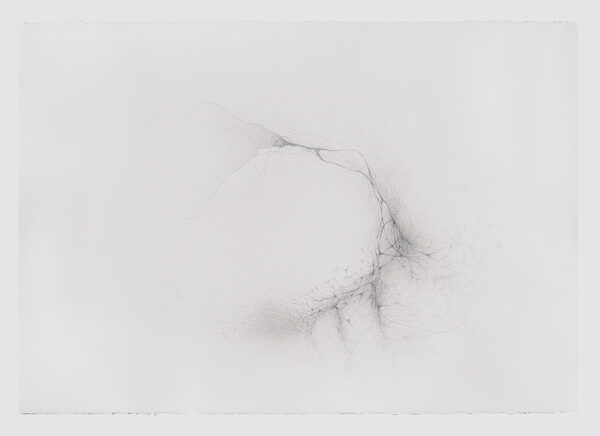

Gustavo Díaz, “Imaginary Flight Patterns V,” 2021, graphite on paper, 42 × 60 inches. The Menil Collection, Houston, Purchased with funds provided by the William F. Stern Acquisitions Fund. © 2024 Gustavo Diaz. Photo: Tom Dubrock, Courtesy of Sicardi Ayers Bacino

In New York, without access to his “brain” and “arms” — as Federman referred to his computers and laser cutter — Gustavo focused on graphite drawing. While the cut-out pieces are certainly delicate, the more recent ones — rendered on jewel-toned paper — have a solidness to them that contrasts rather starkly with the impossibly gossamer-like quality of his pencil marks. One such drawing (Imaginary Flight Patterns V) was recently acquired by the Menil Collection, and currently hangs in the exhibition Out of Thin Air: Emerging Forms. It reminds me of the retinal imaging studies my grandmother’s macular degeneration required, with her veins curling around the globe of the eye and the gauzy, threadbare retinal tissue swirling in the center.

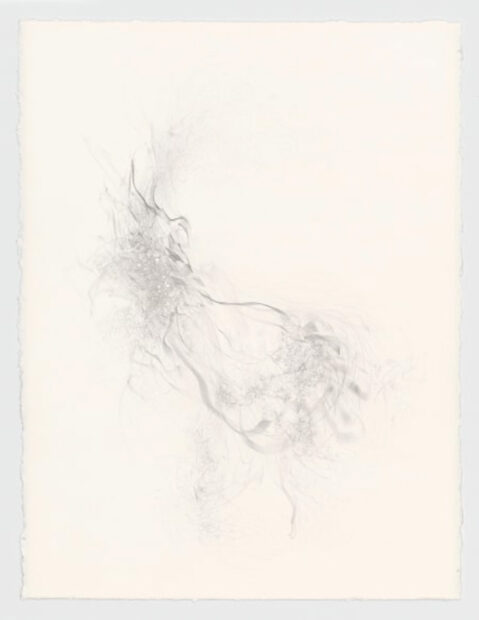

Fastidious doesn’t begin to describe the exigencies of Gustavo’s draftsmanship: the pressure he uses to set down some of the marks is so slight, he’ll use his left hand to hold back the right’s weight. At a distance, the works in one of his series — fittingly titled Paper Membrane — look like the faintest traces of smoke, or silk threads. At close range, its makeup of lines, dots, and circles is almost imperceptible on the smooth surface of the paper. When we talk about his choice of materials, he sounds earnestly pained — often, he’ll discard most sheets in the paper shipments he receives, as the transport marks them with all sorts of indentations or folds. Even the slightest stipple on a page torments him.

Gustavo Díaz, Tearing through space’s structure, the horizon ceases to exist,” from the series: “Paper Membrane,” 2024, graphite on paper, 30 x 23 inches

One of Gustavo’s gallerists, the recently deceased Dan Pollock, once called him “compulsive, and a little bit mad, in the best possible way.” Behind the perfectionism is an earnest curiosity about the natural world and the organizing principles behind complexity — but ultimately, his is a drive for excellence. “I am very critical about my work,” he tells me. “It can always be better”.

III. VOCABULARIES

The case with the microscope was what Gustavo calls “a semantic constellation” — a didactic display of sorts, for the viewers to get a sense of the ideas behind his works. There is a similar installation in Wild Wind, Subtle Breeze, his current show at Sicardi: two tables pushed together in the middle of the main gallery. One table holds a library, a set of meticulously labeled plastic folders with printouts of academic papers, journal articles, and other resources on the topics that interest him: Borges, the composer Olivier Messiaen, dissipative structures, the neuroscientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Brownian motion. Arranged on the surface of the next table is a small collection of bird feathers, and what at first looked to me like samples of the jewel-toned laser-cut drawings, in blue boxes. Later, I understood they were studies; sketches of vortexes, swirling fields, and network modeling. Gustavo quoted each in the mass of vectors of the large, framed works on the wall, like a melody repeated in the movements of a musical composition.

Music, physics, literature — there are references to all in his works, but when I ask for other visual artists he might admire, he is immediately apprehensive. A sidelong glance tells me he suspects me of blatancy, and for Gustavo, to lack subtlety is a great sin: “Obviousness and superficiality, they hurt”.

Buried among the folders in the gallery, I found a reference to Lee Bontecou, an artist whose drawings also hang in Out of Thin Air at the Menil. Better known for her tenebrous wall-mounted sculptures, Bontecou discovered she could use her welding torch to produce the blackest soot, which she layered with charcoal and graphite to draft “worldscapes”, abstract drawings of what appear as shadowy, fantastical realms. While Bontecou’s non-literary, speculative fictions are not the most formally alike to Gustavo’s drawings, their careers do have correspondences: Bontecou famously renounced the New York art world in 1970 to work in relative seclusion in rural Pennsylvania, and she took inspiration from the natural world, as does Gustavo. “I think he and Bontecou both embraced the exploratory or speculative nature of drawing,” Kirsten Maples, curator of Out of Thin Air, told me.

Gustavo Díaz, “The mysterious man, the secret friend of O. Messiaen, resists letting the birds go. Seeing that his failure is inevitable, he collects a few feathers with the intention of eternalizing their flight… minutes later, a bird came down the walk …. someday in May of 1981,” 2024, cut out paper, 28 1/32 x 85 7/16 inches

It’s the Russian avant-garde to which I find myself comparing Gustavo the most, especially the abstract, Constructivist sculptures of Naum Gabo. Gabo had exceptionally broad interests — electromagnetism, materials science, the mathematics of spirals — and his most famous works use rigid plastic frames to stretch nylon microfilaments in regular patterns. To walk around a Gabo sculpture feels like observing volumes taking form. Similarly, in Gustavo’s drawings, it’s not the genesis of matter but its organization that occupies the eye, a topic of inexhaustible interest across numerous academic disciplines today.

Russian constructivism and suprematism had an outsized impact on Argentinean artists of the 20th century — a lesson displayed in comprehensive detail in the Latin American art galleries of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. But while the formalism of geometric painting is certainly buried among the visual precursors to Gustavo’s current practice, it is hardly enough to explain him as an artist. The layers of meaning in his oeuvre are bottomless — cosmic noise, spatial distribution, fluid dynamics — topics of present-day research whose findings are interestingly equivocal. These transcendental phenomena, drawn together on the surface of paper through the sweep of his hand, are what distinguish Gustavo’s work and will make him a definitive figure in 21st-century art. His interest in ambiguity and the indeterminacy of certain scientific pursuits belongs squarely to the present, contrasting starkly with the exactness of many early 20th-century art movements when science portrayed the world as orderly, coherent, and predictable.

IV. DESTINATION

“Me, I feel like an immigrant everywhere,” Gustavo tells me when I ask about home: “My home is my workbench.” 13 years ago, Mari Carmen Ramírez, formidable curator of Latin American Art at the MFAH, purchased one of his works for the museum’s collection, and as life became more challenging in Argentina, he mulled that event as a possibility. “My life began to worsen. Something must be done,” he reasoned. After María Inés Sicardi visited him in his studio in Cariló and decided to add him to her gallery’s stable, Houston seemed like a natural destination. “Like everyone who emigrates, I was searching for an opportunity.”

Halfway through the talk at Sicardi, I notice a woman recording the event. Tan and athletic, with green eyes and dark hair tied back, I meet her later that evening: Graciela, Gustavo’s wife. His young son is also in attendance, smiling a bit timidly among all the adults. Where Gustavo has been guarded in our conversations, Graciela is gregarious, telling me of their initial meeting at an art school he founded in Argentina, Centro NOUS (Greek for “mind”), and their coup de foudre at arteBA, Buenos Aires’ legendary art fair. “Behind each work, there are hours of conversations between us,” she tells me when I ask about her role in Gustavo’s art practice. Friends and neighbors come up to us as we’re speaking, hugging and congratulating her for Gustavo’s recent achievements: his return from New York, the Menil’s acquisition, and more upcoming events to talk about his work. It strikes me that, together, they have built a community in Houston that is remarkably supportive of Gustavo: not only through the gallery (“They are like my family”, he says of them) and the many curators in the city who have actively promoted his work, but through the formidable expat community in this extraordinarily rich city, where acquaintances become friends, and soon after, our champions.

The day before his public talk at Sicardi, I ask Gustavo why he’s chosen this moment to speak publicly about his work. He starts reflecting on the responsibilities of artists towards their audiences — a topic he has told me before can skew “dangerously arrogant” — only to conclude rather succinctly: “I’ve been silent for twelve years. I think it’s the moment for speaking again.” Today, undoubtedly, Houston is listening.

Gustavo Díaz: Wild Wind, Subtle Breeze is on view in Houston at Sicardi Ayers Bacino through December 7 and in the group exhibition Out of Thin Air at the Menil Drawing Institute through January 26.

Recent Comments