Golden hour is generous in El Paso, casting a golden-pink tint over its mountainous sand-colored terrain, a color both natural and manufactured by this city’s blend of grit and desert sun. For two years now, I’ve come here around Halloween and Día de los Muertos, timing my visits to overlap with holiday and research seasons. El Paso feels transitional and settled all at once, rooted in the complex material and cultural exchange of the border. On each visit, I collect these experiences in my notebook, drawn by the distinct language of material and architectural production here.

At the Tap Bar and Restaurant, I find myself among a bilingual crowd. Karaoke floats from the stage: a mix of Mexican ballads, interrupted occasionally by American Grunge. The fonts on Tap’s menu echo another Southwestern haunt, Pasqual’s in Santa Fe. At first glance, it’s just an italicized, all-caps typeface with long-serifed letters — but details like this anchor me to the region, reminding me how production and replication shape a collective aesthetic.

El Paso’s built environment mirrors this complex, layered culture. The downtown area is a mix of Victorian façades and brick government buildings accented by ribbon glass exteriors, a kind of aesthetic “Brusselization” that juxtaposes historic structures with stark modern forms. Around Segundo Barrio, brick and plaster buildings stand beside exposed plate glass storefronts, reflecting a border town that absorbs influences from both sides with minimal separation.

Part of this visit, though, is about seeing El Paso’s creative community through the lens of artists like Ingrid Leyva. Ingrid is a lens-based artist who feels deeply tied to both sides of the border. “I’m very “fronteriza” in that sense,” she says, explaining how El Paso was the setting for her childhood holidays, dollar store trips, and family gatherings. She’s been working on a project in Segundo Barrio titled “Ultra Violent Lights”, a series of overexposed portraits that capture the city’s heat and the toll it takes on bodies and lives. “The summer here is extremely violent in terms of the heat,” she tells me, describing how these photographs reveal a shared endurance. The intense light burns out certain features, almost erasing parts of her subjects, underscoring the ways people here are marked by an unforgiving sun.

Driving through Duranguito, one of El Paso’s oldest neighborhoods, we pass murals by Los Dos and Victor Casas. These works confront contemporary issues like labor and migration, pointing to a deeper theme of border economies — especially relevant when I think of the region’s industrial ties to Juárez. There’s even a SHEIN mural here, a reminder of how border industries exist within the network of global fast fashion. Production, as much as art, is a backbone here, underscoring the ways people on both sides of the border survive and make a living.

El Paso is as much a hub of material and aesthetic production as it is a border city. Through encounters with artists like Ingrid and the architecture that defines its neighborhoods, I see a city forged by its layered histories, its markets, and its landscapes. In this review, I’ll be looking at the exhibitions that reflect and expand on these themes, drawing from the narratives of artists and the city itself to understand how El Paso represents, produces, and defines Texas culture along the border.

****

My visit to the El Paso Museum of Art began with a vibrant fashion pop-up in the lobby, progressing through thought-provoking galleries downstairs, and culminating in the upstairs Selena exhibition. While the permanent galleries were closed for installation, the dynamic mix of temporary displays made for a memorable journey.

The entryway of the museum welcomed visitors with a pop-up by Carla Fernández, the celebrated Mexican fashion label known for blending traditional motifs with contemporary design. Highlights included the Chaparra, a signature piece featuring intricate leather threadwork, and a striking denim jacket crafted in collaboration with Levi’s, adorned with metal carrutos — tiny funnels that clang melodically with movement, intended to ward off malevolent spirits.

The label’s ethos emphasizes handmade craftsmanship, minimalist patterns, and timeless silhouettes inspired by Mexican heritage. One-size tunic garments, among other designs, reflected an inclusive and versatile approach. However, while the artistry was captivating, the price points — starting at $270 — could alienate some viewers, especially in a museum setting.

Their ethos, outlined in the bilingual book “La Fiesta de la Moda,” positions their consumers as collectors, a sentiment that reinforces the brand’s dedication to preserving and elevating traditional Mexican craft. A PDF version of this book is available on their website.

The theme of craftsmanship extended into the first-floor gallery in the exhibition From the Collection: Two Centuries of Sculpture and Design. Among the standouts was Robert Lang’s Giraffe (2008), an oversized origami sculpture constructed entirely of folded paper, supported internally by a delicate steel rod. Its precision and whimsy evoked a sense of wonder, bridging traditional craft and contemporary ingenuity.

Nearby, Jorge Rojas worked in situ on Corn Mandala: Mictlān, commissioned by the museum as the eighth entry in his series Gente de Maize/People of the Corn. This intricate work, inspired by the Disk of Death (Disk of Mictlantecuhtli) — a pre-Hispanic artifact — reimagines Aztec mythology with a focus on the cyclical nature of death and rebirth.

Museum wall text for Corn Mandala: Mictlān:

“Corn Mandala: Mictlān expands on the artist’s original works and focuses on the Disk of Death, a pre-Hispanic sculpture possibly depicting Mictlantecuhtli, the Aztec god of death and ruler of Mictlān, the underworld of Aztec mythology… The basaltic rock disk sculpture, partly destroyed, features a skull with the tongue out and a ‘halo’ possibly symbolizing the sun’s cycle of death and rebirth.”

This juxtaposition of ancient iconography with contemporary art reinforced the museum’s dedication to cross-temporal dialogue.

In the black-box gallery, a retrospective celebrated the late El Paso-born experimental filmmaker Willie Varela (1950–2024). His oeuvre combined experimental Super 8 films, photography, and video art, exploring themes of identity, contradiction, and cultural nuance.

The retrospective featured vignettes with unsteady camera work and gritty textures, evoking an unsettling intimacy. From rippling water to businessmen stranded in airports and George W. Bush descending Air Force One, the works challenged viewers to piece together their fragmented narratives. Varela’s inspirations, including Stan Brakhage and Brian Eno, were evident in the haunting experimental textures and psychological layers of his videos.

Accompanying the moving images was a vitrine of street photography (1998–2000) and ephemera from Varela’s 2004 Artpace exhibition, offering additional context to his legacy as a self-taught artist who gained recognition in major institutions like MoMA and the Whitney Biennial.

The museum’s upstairs galleries were dedicated to a temporary exhibition on Selena, celebrating her cultural impact and iconic status. (Details of this segment could be expanded based on your notes.)

The El Paso Museum of Art offered a rich tapestry of experiences. From Carla Fernández’s fashion pop-up to Jorge Rojas’ meditative mandala and Willie Varela’s visceral retrospective, the museum captured a compelling dialogue between tradition and experimentation, local and global narratives, and the ephemeral and enduring.

The upstairs exhibition Selena Forever / Siempre Selena revisited the iconic Tejano singer’s life and legacy. Grounded by photographs from John Dyer, a San Antonio-based artist whose work I’ve encountered before at the McNay, the exhibit also incorporated “drag” outfits inspired by Selena’s dazzling, rhinestone-studded stagewear. These additions reflected her enduring influence on fashion and identity expression, particularly within the Latin American and queer communities.

One striking work in the show was Gary Saderup’s 1995 portrait of Selena, rendered in his signature photo-realistic style. The exhibition overall leaned heavily on fan-centered ephemera and reproductions, with little scholarly interpretation or deeper contextualization of Selena’s cultural impact.

While Selena has become a powerful symbol of Latin American pride and achievement, exhibitions like this often fail to move beyond celebrating her image as an icon. They rarely explore her life’s complexities or her role within broader cultural and economic structures. This absence of depth suggests a recurring challenge in archiving and honoring pop stars’ legacies: they are often treated as commodities rather than as artists and workers with rich histories.

For a museum like EPMA, which typically excels at creating engaging, community-centered programming, this reliance on fan artifacts raises questions about how these archives are maintained, stored, and shown. The public’s voice is absent in my question: Do they like these shows? Selena’s story deserves the same critical and curatorial rigor applied to other cultural figures, and a deeper dive could provide audiences with a more nuanced understanding of her artistry and significance.

****

Nestled in the mountains, the University of Texas at El Paso Rubin Center’s exhibition Mud + Corn + Stone + Blue / Barro + Maíz + Piedra + Azul bridges local and global perspectives on agriculture, labor, and migration within the Americas. Curated by Laura Augusta, this thoughtful presentation begins with the U.S. Farm Crisis of the 1970s and spirals outward, connecting policy shifts, cultural traditions, and artistic expressions through material themes like mud, corn, stone, and blue.

Assistant curator Henry Schulte provided a brisk overview, detailing the show’s expansive narrative and the diverse artworks’ global journeys to El Paso. A notable strength of the exhibition lies in its anthropological lens, which deeply roots these artistic explorations in historical and cultural contexts. Reading materials, such as The Story of Corn by Betty Fussell and Corn: A Global History by Michael Owen Jones, emphasize the show’s engagement with both academic rigor and storytelling.

Corn, as both a material and metaphor, takes center stage. From Angel Poyón’s Kaxlanwäy (a humorous reframing of the cheeseburger as a “foreign tortilla” in Maya Kaqchikel) to Melissa Guevara’s Yunque y Martillo, which poignantly uses dirt from El Mozote to represent the dead, the works reflect deep cultural resonances. These pieces echo indigeneity’s significance and the need to protect its narratives from Western homogenization.

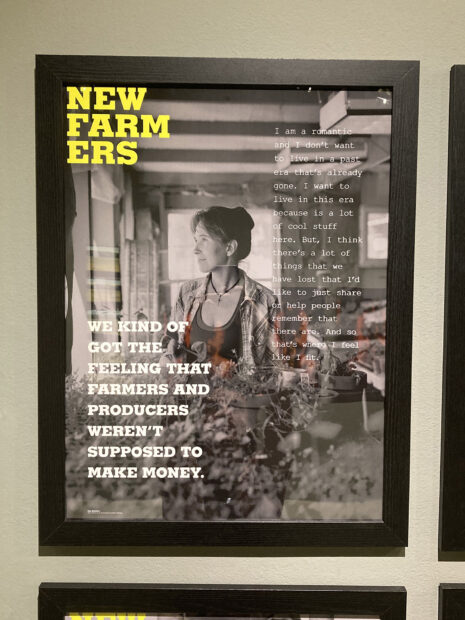

Other standout works include Bryon Darby, Tim Hossler, and Paul Stock’s The New Farmers Project, a photographic homage to Kansas farmers striving for sustainable practices, and Arón Adrián Venegas’s Bracero, which critiques the dehumanizing practices of the Bracero program while honoring its workers’ legacy.

The exhibition’s overarching critique of industrial agriculture and its violent aftershocks — manifested in Central American coups and U.S. monocultural policies — is sobering. Yet, the resilience of “primitive” tools and communal practices highlights enduring strength. As Schulte remarked, in Guatemalan culture, corn “is like family,” a sentiment that encapsulates the profound ties between people, land, and tradition.

This show feels distinctly El Paso in its focus on indigeneity and cultural preservation, but it is also expansive, challenging visitors to reconsider agriculture’s global entanglements and political futures.

****

William Sarradet is the Assistant Editor for Glasstire.

Recent Comments