William Stewart is most certainly an abstract expressionistic, gestural landscape painter, but categorizing his work in the canon of art history feels like trapping a hummingbird. His paintings read like an open window, light pouring through his confident, lyrical brush strokes. Each stroke has its own personality, hovering, rising, and falling like a freshly written cadenza. William is a painter’s painter. Throughout his career in New York, New Mexico, Italy, and Greece [and now Mexico] he has demonstrated passion and commitment. Although he has shown with the likes of Rudolf Zwirner Gallery in Cologne, Germany, he is fiercely independent, wanting to stay true to the painting and its final outcome.

What started as a strong and uncompromising commitment to gestural abstraction influenced by natural phenomena has grown into a mature painterly style. He has peculiar discipline, all nerve and sheer skill, pushing mastery to its limits. His work is about life, sensuality, faith, and the quality of miracles. Bill doesn’t talk about his extraordinary past. He was friends with so many historically important artists but never talks about his important connections to the art world. Ana Mendieta and Carl Andre are just two examples, and he is very close friends with avant-garde visionary Robert Wilson, who is also from Waco and the founder of the Watermill Foundation in New York. Bill has settled on abstract expressionism as his sole method. That’s what people know him for.

–Jina Brenneman, museum curator for the past 30 years, most recently in Taos, New Mexico, where William Stewart lived, worked, and taught for almost 30 years.

Acclaimed artist William Stewart has come back home for a bit, via a long and winding art career that has led him from Waco to New York to Taos to Oaxaca, Mexico, where he now lives and works. His Waco exhibit Dancing Freely is a collection of new abstract oils bursting with vibrant hues that capture the extravagance of light and color that permeates the southern Mexican state. The show continues through December 21 at Art Center Waco (ACW), in the city where Stewart was born but hasn’t exhibited since just after he graduated from the University of Texas. He’s 86 now.

Stewart’s abstract works explode with the essence of light and color that make Oaxaca so visually sensual, rendered through bold brushstrokes and nuanced textures. His art is as joyful and exuberant as the fuchsia bougainvillea that drapes the walls of his home and studio in the mountain-surrounded countryside outside of Oaxaca City, a 500-year-old Spanish colonial city surrounded by even older Zapotec ruins of pyramids and cities. The artist himself is exuberant strolling among his exhibition paintings, especially after cataract surgery in Waco that allowed him to see them on opening night as though he were reconnecting with old friends he hadn’t seen in years. Which he actually did at the opening reception, when a woman introduced herself as a fellow Waco High School graduate and student in one of Stewart’s art classes at Baylor University, which he attended for a year.

When I found out that the gallery that represents him in Oaxaca City was just a block away from where I lived a writer’s expat life for 11 years until the pandemic, I had to meet him. Though I love my adopted city of Waco, like Bill Stewart, I love and deeply miss the starkly bare mountains, lush tropical flowers, and extraordinary artistic pulse of Oaxaca.

I sat down with Bill — after five minutes of conversation, he’s just Bill with no formality — not to talk about the accolade-studded career that he somehow fails to mention, but about painting, inspiration, and yes, Oaxaca.

Susan Bean Aycock (SBA): Why ‘Dancing Freely’ as the exhibit title?

William Stewart (WS): I wrote an artist’s statement for an exhibit this past March in Oaxaca:

My painting is about feeling.

Like looking

Through an open window

And seeing light fall over

A plant, a tree, a face.

It is that experience

Found again

With a brush

On canvas and paper.

Physical

Combative

Gentle

Dancing Freely.

That show had most of the same pieces in it, though not the same title. I liked how it expressed my feelings about painting, so when I sent my information to Art Center Waco, they used it for the title. When I’m pushing paint around, it’s combative and physical. But it’s gentle in spirit, so there is always that contradiction. I paint my feelings and that means freedom to me. I’m dancing freely when I paint. I’m inspired by the light and what I see through the window, but I’m not literally copying it on canvas. It’s about the inspiration that I draw from nature, and the special light of Oaxaca, and channeling that connection. Color is very important to me — how a painting holds that light and color.

SBA: I’ve got to ask: of all the beautiful places in Mexico, why Oaxaca?

WS: Back in the 60s, I was living the beatnik life in New York City and doing very ephemeral work — sculptural things out of all kinds of materials. One piece was purchased by a collector in Germany, and he went on to become a friend and bought other works. I earned enough money to take my first trip to Mexico, where I first fell in love with Oaxaca in 1974. I went back to New York but then returned to Oaxaca in 1977. I also taught painting and drawing for a year at the Instituto de Allende in San Miguel de Allende. Then I drove back with my paintings to San Francisco and had a show with pieces that were more in the direction of the Los Molinos painting, when I used to do more still lifes and landscapes.

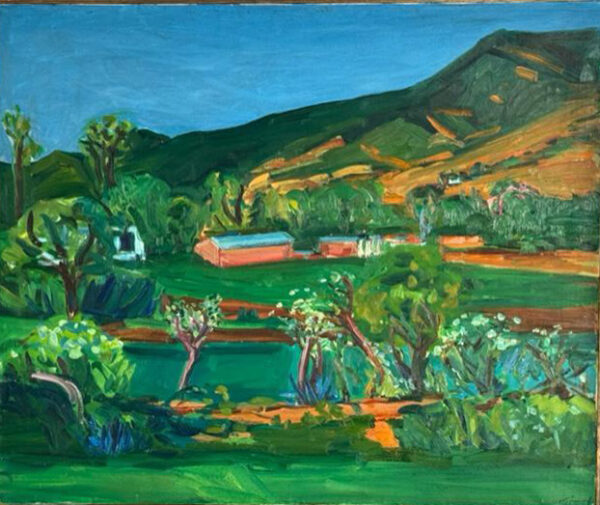

SBA: So about that Los Molinos painting hanging at the back entrance of the exhibit: it’s distinctly unlike the others in this show. What’s the story there?

WS: There’s an interesting story about that. I think you can see in that painting that there’s a strong abstract interest though it’s clearly a landscape. I was painting a lot en plein air at the time and I had painted that in 1977 in an area of Oaxaca called Los Molinos. A man from Taos who lived there bought it and so it stayed there after I returned to the States. When I went back to Oaxaca in 2019, I found that house again and knocked on the door. And can you believe it — the same housekeeper answered the door who had been there more than 40 years ago; she recognized me and invited me in! When the house sold, the new owner didn’t want any of the furnishings or art that came with it, so the housekeeper’s nephew — who was just a teenager at the time but loved art — rescued the painting. He had kept it all those years in his little apartment. They took me to see it, and even though it was dusty and dirty, I still wanted it. So I bought it back. I just brought it back to the States this year, and had it cleaned and varnished. It really doesn’t fit in with the rest of the exhibit, but I love that it’s of Oaxaca and makes a wonderful gateway to the rest of the exhibit.

SBA: Tell me how your style has evolved into your eighth decade and where you find your inspiration.

WS: Abstract expressionist is as good as any description of my painting style. My work has evolved over the years, but it’s always been fairly abstract, and always about light and color. Nature is very important to me for inspiration; it’s in my subconscious even when I’m painting abstractly. I feel like my painting really comes from someplace else; I never plan what I’m going to paint. Some artists make drawings or sketches before painting, but I never do. It’s almost like there’s a dialogue between me and the canvas instead of me thinking what I’m going to do next. Of course, I’m living in an area where I love my surroundings. Sometimes I just walk in my garden and something inspires me to paint. Or sometimes I just get up and have this feeling that I’ve got to paint. I don’t paint every day, but when I feel that a painting is going to happen, I start and the canvas tells me what to do. I paint from my feelings and my subconscious, and there are always surprises. I feel the energy and it feels like I’m channeling the art in a very intuitive way. The painting is talking to me and I’m talking to the painting, and that’s how it evolves. Most of the works in this show are oil on canvas, though there are a few watercolors. Over the years, I’ve worked in different media — charcoal, pen and ink, graphite. Sometimes I’ve done a combination of graphite and watercolor, or even colored pencil and watercolor. But I like to work in oil.

SBA: You talk about how nature and your feelings inspire your work. Do you hope for viewers to have specific takeaways from your art?

WS: I never project on the viewer what to feel from my art. I leave it to them to take from it what they will without explanation. As Picasso said, you can enjoy the sounds of the birds without knowing what they’re saying. I let my art speak for itself.

SBA: Tell me about how Oaxaca influences your painting in this chapter of your life and art.

WS: I spent almost 30 years in Taos, but I left it almost 10 years ago to live in Oaxaca, where I spent some wonderful years in the 70s. I live in Atzompa, about 25 miles out of [Oaxaca] City, and I rent this fabulous house with gardens and views of the mountains. You know, homes there don’t have air conditioning, so we keep the windows open most of the time, and there’s just this wonderful play of light that streams in through the windows at different times of the day. I can see the light over the mountains, and the bougainvillea and jacaranda trees outside, and it’s a never-ending show right in front of me. I’ve been experimenting with color inspired by the people of Oaxaca and their beautifully colored handwoven textiles. I’ve been combining oil and watercolor with cochinilla, a scarlet dye derived from the dried cochineal insect. [Cochinilla] originated in this area and the Spanish took it back to Spain. They still use it for dyeing wool and other materials.

SBA: When did you begin painting and what has that journey been like?

WS: The truth is that I was kind of an outsider kid who didn’t fit into 1950s Waco, and I felt depressed and isolated until I discovered painting at about age 13. For me, it was a form of therapy to deal with that pain. I knew Bob Wilson from growing up here; he and I used to have fun in New York talking about our childhood and being misfits. Bob and I were really close in the ‘60s when he was just beginning his career. We were all kind of struggling but I had begun to have some success, which I kind of messed up, and he went on to be really famous. But I kind of screwed it up, because they wanted me to keep doing the same thing, and I wanted to keep evolving. I was very young and arrogant. There was an art center downtown when I was growing up that had little exhibitions, and I participated in a few shows there when I was just out of UT. It’s been more than 60 years since I exhibited in Waco.

SBA: Tell me a little about the paths that you’ve taken to end up at this point in your life and career.

WS: I left Waco to go to the University of Texas — I couldn’t get out of Waco fast enough — and I earned my BFA and MFA degrees there. Not too long after UT, after I worked at Hardin-Simmons for a year, I got a job at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. I was assistant director of the Education Department, teaching in outreach programs for children. But I wanted to go to New York, so I took a Greyhound bus there. It was the beatnik days, and I got an apartment between Avenues C and D. The bathroom was in the hall and there was a bathtub in the kitchen. I was doing all kinds of menial jobs but finally, I got a job as a teacher’s assistant and became friends with the school’s director and her assistant. They liked me and found me a teaching job at the [Ethical Culture] Fieldston School — a very, very good school — but I turned it down to go to Europe and travel instead. They were furious with me! I had $1,000 and I said, ‘I’m going to Europe to travel and see paintings.’ I lived for a year on that $1000, with a backpack and a Eurail pass. I traveled all the way from southern Italy to Scandinavia, to Sweden and Denmark. I wouldn’t give up that year for anything. I got more of an education in the museums than in any university.

My formal education introduced me to art history and I do think understanding that is important. But I wanted to see the art for real, not on a slide. I even taught art in Mallorca for a year. I would love to go back to Spain. There’s a fresco of Goya in this little, tiny church in Madrid [Ermita de San Antonio de la Florida, where Goya is buried] that I really hope to see again before I kick the bucket. I’ve sold my house in Taos, where I lived, worked, and taught for almost 30 years, but I still have a lot of paintings in a storage unit there. My friend Jina Brenneman, who’s a museum curator, is going to do a video call with me to see what’s there. It’ll be like seeing old friends again. I’m hoping to sell some, but whatever is in my estate will go to the Watermill Foundation upon my death.

SBA: Most of your works in this Waco exhibit are untitled and unsigned. Why is that?

WS: Sometimes I do name my paintings, but the name always comes afterward, like naming the baby after it’s born. But a lot of times, I don’t name them. One thing I do — that some people don’t like — is to sign my oils on the back. I really don’t like to put a signature on the front, because it interferes with the visuals. I think that a lot of abstract painters don’t put a signature on a painting for that reason. I do sign my watercolors on paper with a pencil because it’s less obtrusive and doesn’t jump out at you, but with the oils, I sign them on the back.

SBA: You have such an obvious joie de vivre and it’s clear that you love what you do. How do you keep your art fresh after doing it for so long?

WS: Each time I paint, it’s a new experience — every time I start a painting it’s like the first one I’ve ever done. Feeling that freshness is an incredible gift and privilege. It’s what keeps this old guy going.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

William Stewart is a 2019 recipient of a grant from the prestigious Pollock-Krasner Foundation, as well as a 2015 Emily Harvey Foundation residency award in Venice, Italy, and The Watermill Center residency award in 2017. His work is in the permanent collections at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, The Watermill Collection in New York, Fairleigh Dickinson University in New Jersey, and others.

Dancing Freely is on view at Art Center Waco through December 21

Recent Comments