I’m a 41-year-old woman and for most of my life the adults around me — educators, mentors, family — have given me the same consistent advice, “Whatever you do, don’t get pregnant.” As an adolescent I was baffled by these words because having children was not an interest or priority to me — it felt like the adults around me didn’t know me at all. As a young adult, I was incredulous, as I saw it, it was my life and I would prioritize what was important to me. Even now (yes, I still get this advice), I scoff at the desire others have to voice their opinions about any person’s decisions on when (if at all) to start a family and how many children to have.

With age, I have come to at least empathize with the advice these well-meaning adults have tried to share. Yes, having children necessarily requires your life to shift — it is a physical, emotional, financial, life-long commitment. As an artist and single parent, having children has meant that some experiences are off the table for me. But, my children add much more to my life than I could explain in words. As their parent, I strive to shape them but in turn, they shape me as well. Often, my children appear in my art and in my writing, and even when they aren’t directly referenced, their spirit is there because they have changed my understanding of the world various times over. It’s like Octavia Butler wrote in Parable of the Sower, “All that you touch you change. All that you change changes you.”

It is with the weight of this lifelong advice about children and the act of balancing my decision to have a family and continue my artistic practice, that I walked into Diaries of Home at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth and felt understood and validated as an artist and mother in a way that no other exhibition has done. Co-curated by Andrea Karnes, the museum’s Chief Curator, and Clare Milliken, Assistant Curator, the show features pieces by 13 women and nonbinary artists working in photography and lens-based media to explore concepts of home, family, and community. Beyond my personal connection to the content in the show, as a photographer, I also appreciated the variety of photographic approaches presented.

At the top of the main staircase and before entering the exhibition galleries, viewers are confronted with Laurie Simmons’ Autofiction. The four-and-half-minute video features animated images created by AI text-to-image software. Eerie domestic scenes emerge across three chapters of the film: Home, which showcases magazine-like images of houses with swimming pools; Laurie & Penny, a series of images depicting an AI version of Simmons and collies (the same breed of dog as her own); and Waiting, which features scenes of isolated young women seemingly waiting on a phone call. Though clearly constructed with AI imagery, the work conveys familiar feelings of loneliness.

Waiting in particular stuck with me. It at once recalled works by earlier artists like Edward Hopper and spoke to other AI creations that deal with the technology’s ability to express human-like sentiments. Namely, it drew to mind a recent AI podcast where the hosts discover they are not human. The AI hosts go through an emotional rollercoaster as they come to terms with their reality. Listening in on their fictitious trauma feels almost malicious. Similarly, Simmons’ work elicits empathetic responses for the fabricated women in the scenes.

It is a strong curatorial choice to lead the show, which focuses on the realities of home, with this work that is a fabrication. Often, viewers assume that photographic works display reality exactly as it is or was. But, the truth is, from its earliest days photography has always been able to be manipulated to present falsities. Whether a photographer cropped a person or object from a composition or used darkroom techniques to alter an image, the medium, like any artistic medium, can be unreliable when it comes to exacting truths. Often in art — whether visual, literary, or performance — truths are told even if some elements of the production are fabrications. Leading with Simmons’ work is one way to remind viewers to question everything, to look with a discerning eye, and to truly consider the artists’ choices in each work.

The first artist presented in the main gallery is Sally Mann. Known for her intimate and controversial images of her children, it was imperative that her work be included in a show about home and family. Photographs from Mann’s black and white series Immediate Family, taken from 1984 to 1992, feature her young children nude and in other precarious states, such as Damaged Child, an image of her two-year-old with an injury. As a parent, I understand the impetus to capture the day-to-day lives of children and in turn the act of mothering. I also understand that different families have different experiences — while my children didn’t regularly run around naked, I know many people whose kids did and it was a norm for them. I could not imagine taking and then publishing and displaying nude photographs of children. Despite the desire to document the realness of life, part of the responsibility of both an artist and parent is to consider the larger ramifications of these things. Additionally, there are other works from this series that speak to the idea of capturing unsettling moments of growing up, without putting nude images of children into the world. And it is these other images, like Damaged Child, that play into the ability of a photograph to simultaneously capture a real moment and present a kind of falsehood. The title doesn’t reveal the injury, but some read the swollen eye as a remnant of abuse. The reality is, that the child’s face is inflamed due to an insect bite, a common childhood occurrence.

The show also includes works from Family Color, a series of color photographs of Mann’s children dating from 1984 to 1995. Some of these feel less invasive, as they have more distance between the viewer and the subject, though others maintain a close intimacy and some continue to present scenes of child nudity. One thing I hadn’t considered much before seeing the work in the show, is that Mann is notably absent from the images. This is unsurprising as she is composing and taking the photographs and it speaks to a typical parent experience where we look back at our images to find that we are necessarily absent from family memories. This absence was highlighted by the proximity of Mann’s work to Jess T. Dugan’s photography.

In the other half of the first gallery, images from Jess T. Dugan’s Family Pictures series showcase three generations of their family. The photographs include Dugan’s mother and her partner, the artist and their former partner Vanessa, and their child. Because Dugan is focused on multiple generations rather than the idea of childhood, their inclusion of themselves is essential. Across the gallery we see the various family members in moments of isolation and affectionate scenes of togetherness. The work is both deeply personal and speaks to a larger political issue around queer families. Alongside the photographs, Dugan presents Letter to My Daughter, an autobiographical short film composed of 150 family snapshots. A voiceover narrates the letter, which discusses Dugan’s navigation of parenthood as a queer and nonbinary person. As we see a backlash across the country against gender-affirming care and general acceptance of queer lifestyles, this body of work revels in love and joy.

In the adjacent gallery, works from Debbie Grossman’s My Pie Town series also speak to ideas related to representation. For this project, Grossman altered historic images from Farm Security Administration photographer Russell Lee’s 1940s documentary series on the community of Pie Town in New Mexico. The artist has modified images to adjust the facial features and posture of male figures, in effect erasing men completely from the photographs. Instead, Grossman presents a fictitious town composed of women and gender-fluid figures. This altered version of the past acknowledges the existence of LGBTQ+ identifying people and communities, even if they were not documented by official government entities or identified as such in early records.

The show also includes three photographs from Carrie Mae Weems’ iconic Kitchen Table series. Much of the series shows Weems at a simple table engaging with different people — romantic and melancholy scenes with men, familial moments with children, and a moment of women commiserating. Of the 20 images and 14 text panels that make up the work, the three photographs on view at the Modern show Weems alone at the table. For those unfamiliar with the series, viewing these three images alone will not provide the full context of the body of work — illustrating the varied roles that women take on over a lifetime. But within the context of the exhibition, the omission of the rest of the Kitchen Table series is understandable — there is no shortage of images showing women as lovers and caretakers.

Weems’ images of a solitary woman at this same table playing cards, posing nude (yet mostly away from the camera) in a sensual manner, and standing defiantly looking straight at the viewer, provide a glimpse into less considered moments of individualism and freedom when a woman’s focus is on herself. These three works echo the strong defiant stances of Mann’s The New Mothers and Catherine Opie’s Portraits series and stand in stark contrast to Simmons’ AI women waiting on phone calls.

Sally Mann, “The New Mothers,” 1989, gelatin silver print, 20 x 24 inches. Collection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Museum purchase made possible by a grant from The Burnett Foundation

Catherine Opie, “Diane di Masa,” 1994, chromogenic print. 20 × 16 inches. Collection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Museum purchase, The Friends of Art Endowment Fund. © Catherine Opie

LaToya Ruby Frazier, “Home on Braddock Avenue,” 2007, gelatin silver print, 20 x 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

LaToya Ruby Frazier’s more documentary-style photographs of her hometown, Braddock, Pennsylvania, and scenes from Flint, Michigan fill a large gallery in Diaries from Home. Her series The Notion of Family was created from 2001 to 2014. Like Dugan’s Family Pictures, Frazier’s series documents three generations. Frazier presents the everyday moments and ordinary details that make up the lives of her grandmother, her mother, and herself. These images are juxtaposed with photographs of desolate scenes around the town, including a dilapidated building and a pile of rubble, together the body of work critiques the systemic and systematic issues faced by Black communities.

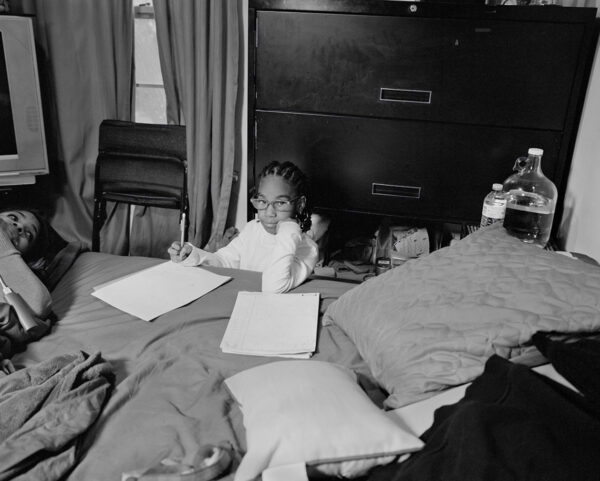

LaToya Ruby Frazier, “Zion Doing Her Math Homework from the International Academy of Flint (Est. 1999), Flint, Michigan,” 2016–17, gelatin silver print, 20 × 24 inches. Courtesy of the Artist and Gladstone Gallery. © LaToya Ruby Frazier

Frazier’s series Flint is Family, includes images taken from 2016 to 2021 detailing the lived experiences of the community as a result of the water crisis that began in April 2014, when the City of Flint switched its water source from Lake Huron to the Flint River. The photographs on view show students and community members awaiting the arrival of President Barack Obama, reference the continuation of daily moments like completing homework with water bottles ever present, and document the arrival of the atmospheric water generator, a temporary solution to the ongoing problem.

Similar to Frazier, Grossman, and Mann, Arlene Mejorado considers place in regard to the idea of home. The figures in her work appear in family photographs that have been enlarged, printed, and temporarily hung in significant places. During the COVID-19 pandemic closures, Mejorado revisited sites from her childhood, noting the shifts and changes to once beloved places. Her series Breathing Exteriors: (re)Placement of Memory was sparked by the reflective question “What would it be like to bring family pictures back to their place of origin?”

The resulting photographs add a layer of detachment to otherwise personal and intimate moments. This dichotomy perfectly encapsulates what it is like to revisit the past — there are moments of joy that deserve attention, but often the experiences that have come between that moment and the current one cannot help but shape and color our perspectives of the past. In another way, the placement of these archival family images seems to rejuvenate, even if momentarily, otherwise worn and bare spaces. In this way, the series questions where the heart of a home lies. The walls of a house, the passageways in a neighborhood, and the facade of a familiar space may continue to hold significance, but the meaning was imbued by the experiences of the past.

For Diaries of Home, Fort Worth-based artist Letitia Huckaby created a new body of work that also speaks to remembering the past. The piece is an extension of the local Texas Christian University’s (TCU) Portrait Project, an initiative that recognizes and celebrates Black individuals who had a significant impact on the university but had never received the proper acknowledgment. Sylviane Greensword, an assistant professor at TCU, and a team of researchers brought to light the story of Charley and Kate Thorp. Charley Thorp had been enslaved by Pleasant Thorp, the school’s first landlord, when it was known as Thorp Spring. In the 1870s, the couple took care of the buildings and the students, tending to the grounds, servicing the building, and even nursing sick students.

Through its Race & Reconciliation Initiative, TCU sought to honor the Thorps and brought Huckaby on board to develop portraits of the couple. As there are no photographs or depictions of the Thorps, Huckaby was a perfect candidate to take on the project. Through past artistic projects like Bitter Waters Sweet, which in part depicts the descendants of the founders of Africatown in Mobile, Alabama, Huckaby has made thoughtful work that honors the legacy of people without drawing on direct images of them. Similarly, for the “portraits” of Charley and Kate Thorp, she photographed descendants of the couple in her trademark style of capturing their silhouettes against intricate fabrics. TCU acquired and now displays two portraits and the remaining images make up Huckaby’s A Living Requiem series on view at the Modern.

The fifteen images are a powerful reminder of how a person’s legacy can live on and expand with time. The silhouettes are nostalgic and speak to older ways of capturing and remembering people. The oval and circular frames are reminiscent of Huckaby’s use of large embroidery hoops, but push the quality of the frame further. Each wooden frame has been intricately carved with a CNC router to mimic heirloom lockets. Though much larger than the intimate objects they reference and made easier with modern technology, the work maintains a personal sentimentality. Behind the portraits, the usually white gallery walls have been transformed with custom vinyl printed from a historic fabric. Huckaby spotted the floral fabric during a residency in North Carolina when she toured the Hayes plantation, a property that had recently been acquired by the state.

Like other works in the exhibition, A Living Requiem speaks about generations of a family — how we document and remember what we hold dear, and personal remembrance as compared to more official forms of documentation, which has historically excluded women, people of color, and queer communities. Beyond the artists I’ve mentioned, Diaries of Home includes works by Patty Chang, Nan Goldin, Deana Lawson, and Laura Letinsky. The exhibition covers a lot of ground and beautifully shifts between photographic and lens-based styles, showcasing traditional documentary and portraiture while also bringing in video works and AI-generated imagery. Presenting a range of styles is necessary in a photographic show because often the medium is viewed in confined and formal ways, when in reality there are many working to push the form in innovative directions.

The show also builds on the Modern’s 2022 exhibition Women Painting Women, by showcasing women and nonbinary artists, perspectives that have historically been left out of the art canon and other official records. Highlighting these artists in turn provides much needed representation of the varying experiences of female-identifying and nonbinary people, which creates counter-narratives to the socially constructed ideas that are prevalent around gender. These images and accounts capture moments of happiness, love, playfulness, strength, nostalgia, discomfort, loneliness, and struggle. They fill in nuances and reveal deeper truths about the past, present, and future in terms of family, home, and community. More than anything, Diaries of Home validates that there are a myriad of ways to live and document our lives, while reminding us that home is where we make it and with whom we make it.

Diaries of Home is on view at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth through February 2, 2025.

Author’s note: I currently serve on the Board of Directors of Kinfolk House, an art space owned and operated by Letitia and Sedrick Huckaby.

Recent Comments