Glasstire’s staff and contributors share which Texas-based shows, events, and works made their personal “best” lists for 2024.

****

Installation view of “Sheryl Anaya: Absurd Appetites (Tables for Two).” Photo: Kevin Todora, courtesy of Cluley Projects

Sheryl Anaya: Absurd Appetites (Tables for Two) at Cluley Projects, Dallas.

Looking back at all of the art I saw in 2024, one of my favorite shows was the first opening I attended this year on January 6. Sheryl Anaya’s solo exhibition, Absurd Appetites (Tables for Two), at Cluley Projects was both playful and charming with its daintily clad pears and cutesy butter designs on handmade dishes, yet it packed a punch in confronting themes of domestic labor, gender relations, and queer companionship. I loved every small detail of this intimate exhibition and can’t wait to see what Anaya does next!

Dallas Contemporary Staff Exhibition at the Dallas Contemporary.

As a fellow museum worker, I just love seeing the artistic talents of the staff making the magic happen behind the scenes at an art institution. The Dallas Contemporary’s inaugural staff exhibition featured a diverse array of mediums and disciplines, celebrating the individuals whose creativity and drive exemplify the spirit of the Dallas Contemporary. The Visitor Services team was always on site and happy to discuss their work with visitors — my favorite part! I look forward to seeing what exhibitions and programming their staff hosts in 2025.

****

Rebecca Manson: Barbecue at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.

Perfect for a summer show in Texas, Rebecca Manson’s Barbecue installation was a feast for the eyes. Depicting a backyard barbecue gone wrong, the site-specific installation filling The Modern’s elliptical gallery consisted of over 45,000 individual ceramic elements. The immersive scene featured an overturned grill set among piles of leaves that contained a wide variety of scattered objects including cuts of meat, playing cards, and matches.

Melissa Miller’s “Wild Grapes and Herons” installed at the University of Houston-Victoria. Photo: Bill Kennedy

Melissa Miller’s Wild Grapes and Herons at the University of Houston-Victoria.

Commissioned by the University of Houston’s public art system, Melissa Miller’s bronze sculpture Wild Grapes and Herons was unveiled this summer in Kay’s Grove on UHV’s campus. Dramatically depicting silhouettes of herons surrounded by a cast of other native flora and fauna, the sculpture marks a new direction in outdoor work for the artist.

****

Backs in Fashion: Mangbetu Women’s Egbe at the Dallas Museum of Art (through August 3, 2025).

Sometimes humble objects speak the loudest. This long-running show of Mangbetu egbe or “back aprons” is a perfect example of how utilitarian items can surpass their primary use and in ways unexpected speak across time and culture. The small gallery of egbe at the Dallas Museum of Art stopped me in my tracks as I noted their tangible force of character; each vestment is uniquely crafted and feels alive with energy and material elegance.

First created as a tool for comfort and modesty, the aprons are meant to cover the wearer’s backside. The colonial history of the Democratic Republic of the Congo clarifies some of the reasons for these artworks: the garments were worn on mostly ceremonial occasions or when foreign tourists visited. Yet, what is fascinating — at least to me — is how powerful they are as objects. They read like small sculptures, devastatingly direct paintings, and of course satisfyingly crafted apparel. The graphic mark-making and scattering of thread remnants accentuate each section of the rounded forms, beautifully highlighting the plantain leaves, braided raffia, corn fibers, and natural dyes used to make the egbe.

This memorable exhibition proves that human artistry can transcend the limits of our lifetimes, locale, and sometimes even functional intent.

****

The film Les Mystères du Château du Dé by Man Ray at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston presented four films by Man Ray, including his Les Mystères du Château du Dé from 1929. The films were accompanied by a soundtrack created by Sqürl, the duo of Jim Jarmusch and Carter Logan performing on guitars and synthesizers during a tour of the films through France in 2023, 100 years after the premiere of Le Retour à la raison, the first film on the program. Man Ray wrote in his autobiography Self-Portrait that he played his jazz phonograph records when showing the films, so the intention was not to have them seen in silence. The Sqürl soundtrack is beautifully responsive to the films in a subtle and pleasing way. The poetic imagery of all four films ranges from the delicate to the sensual to the absurd to the wildly abstract. One gets the impression that to Man Ray the process of filmmaking was like a playground where even the physical substance of the film itself was part of the fun and experimentation. In Les Mystères du Château du Dé, his last and my favorite film, as the guests explore the mysterious castle of chance, arrived upon by a toss of the dice, Man Ray asks “Do our actions linger like ghosts?”

Myra Melford’s Fire and Water Quintet at the Menil Collection’s Cy Twombly Galleries, Houston. Read our review here.

Nameless Sound and the Menil Collection presented pianist and composer Myra Melford’s Fire and Water Quintet performing music inspired by the work of Cy Twombly. The evening was magical as the music flowed from these powerfully creative musicians: Myra Melford, piano; Ingrid Laubrock, saxophone; Mary Halvorson, guitar; Tomeka Reid, cello; and Lesley Mok, drums. In the welcome company of Twombly’s 30-foot masterpiece Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor), the performance became an immersive multidisciplinary conversation between visual art and music.

****

Sarah Sze, “Slow Dance,” installation detail, 2024, paper, string, aluminum, mixed media, video projection, and sound, dimensions variable, courtesy of the artist, © Sarah Sze, photo: Brenda Melgoza Ciardiello

Sarah Sze at the Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas. Read our review here.

I was surprised that I was so drawn in by the constellations of flickering images in Sarah Sze’s installations at the Nasher Sculpture Center this past winter. How did she manage to make flashing, miniature photographs eye-catching in the for-Instagram, over-saturation of our photo-crazy world? Yet, I visited the exhibition at the Nasher Sculpture Center, consisting of three new, site-specific mixed-media installations, three times over the course of the first two months it was on view. I simply couldn’t get enough of the startling way in which Sze managed to take two-dimensional ideas, and make them objects with intense, relatable physicality: memories made real somehow. She gave me a sense that I was experiencing, living — not just looking. The work was intensely, visually mesmerizing despite its delicate impermanence. The installations were primarily composed of light, shadow, and projected color — and were held together by a startlingly delicate web of tenuous strings and weights made of discarded art supplies and random objects from the artist’s environment. One wrong move — a curious five-year-old — and the entire thing would have come down. Like all the kids I saw, I was drawn in again and again: poetic oscillation of scale creating scenes that existed somewhere deliciously between sublime overwhelm and intimate conversation.

Despite its undeniable beauty, I was struck by the cleverness of Sze’s critical probing at the realities (or surrealities) of our now largely image-based existence. The virtual, constantly evolving world in which we live — largely through tiny personal communication devices — results in a fractured but nevertheless collective memory. I still can’t decide if this virtual culture — like the largest of the three installations, Slow Dance, blinking on and off again continuously with new images that become new truths which become new memories — actually brings us closer together through perceived collective experience/remembering or pushes us further apart into loneliness. What does a constant rotation of flimsy, 24-hour-only-instagram-story half-lives which are forgotten almost as soon as they are seen mean for meaningful recollection? Is it actually living when it happens online?

I haven’t forgotten her delicate, web-like installations, but I wonder if their impermanence isn’t yet another jab at the absurd, dizzying merry-go-round of the attention economy in which we are all a little bit trapped. I’d happily get lost again in her cinematic blank sheets of watercolor paper and strings, all my sunsetting hopes and dreams tethered to reality only by a suddenly substantial spare paperclip or two.

****

Jonah Freeman + Justin Lowe, “Sunset Corridor,” installation view, 2024, mixed media, dimensions variable. Courtesy of San San International © Jonah Freeman + Justin Lowe. Photo: Evie Marie Bishop

Jonah Freeman + Justin Lowe: Sunset Corridor at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. Read our review here.

I spent much of the year in India on a Fulbright Award, so missed many important exhibitions throughout the state. I trust my colleagues will highlight them. Both of my “best of 2024” choices are currently on exhibit.

Collaborative artist duo Jonah Freeman and Justin Lowe transformed the Modern’s upstairs permanent collection galleries into an immersive multilayered installation. The overarching narrative is the premise that San Francisco and San Diego merge into one city. Imagine sci-fi futurism with references to the tech sector, drug and music counterculture, new-age spirituality, alchemy, and more. I imagined myself as a visual archeologist from the future experiencing a vast wunderkammer, attempting to decode the layered narratives of each object. An experience where the unreality of the invented world seeps into our current “real” world.

Chivas Clem: Shirttail Kin at the Dallas Contemporary (through January 12, 2025).

Chivas Clem’s photographs of young transient men in Paris, Texas evoke the words desire, trust, vulnerability, intimacy, and comfort in one’s body. The images are sexy and gritty. They also speak to larger themes of dismantling the cowboy trope, the result of the prison-industrial complex, epidemic opioid addiction, and the disintegration of the farming industry leading to poverty and joblessness. In our post-election haze, Clem’s work takes on a greater importance. Returning to a homeland that was openly hostile to him as a child and creating portraits that make visible what has been invisible is an act of courage and defiance. In a state that is actively trying to revoke LGBTQ rights, it is important to have this work seen.

****

Deborah Keller-Rihn at St. Mary’s University, with “Lauren, at 26: Protector of the Environment” (2008) on the right. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Deborah Keller-Rihn: The Evolution Of A Feminine Mythology at St. Mary’s University, San Antonio.

I am acknowledging two under-the-radar exhibitions. The first is Deborah Keller-Rihn’s The Evolution of a Feminine Mythology, a 30-year retrospective held at St. Mary’s University as part of Fotoseptiembre. Commencing with hand-colored darkroom prints of her daughters for her master’s thesis Symbolic Transformations: The Creation of a Personal Mythology, the show traces Keller-Rihn’s subsequent explorations of Tibetan Buddhism and Hinduism. It draws on photographs taken in India featured in several of her previous exhibitions, as well as local women situated in mythic contexts, including one who represents the multi-armed goddess Tara, which the artist regards as “one of the earliest feminists.” She also utilizes her daughter Lauren as the Protector of the Environment on the banks of the San Antonio River. Keller-Rihn’s Glimpses of Eternity series features women, both young and old, in mythic and historical poses. Keller-Rihn delves deeply into the mythic dimensions of feminine iconography and their sources, but always with concern for the individuality of her female models.

Phantasms and Fever Dreams at Bihl Haus Arts, San Antonio.

Phantasms and Fever Dreams featured the work of Michelle Love and Marco Antonio García. The latter artist, afflicted with cancer, died soon after the opening. The closing reception served as a celebration of García’s life, including a performance by the band Dharma Paax, for which he had played several instruments.

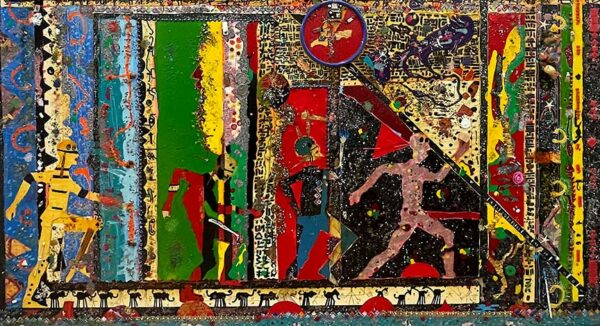

Marco Antonio García, “Crossing Dimensions” (detail), undated mixed media painting on canvas. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova at Bihl Haus Arts

A self-taught artist, García produced complex, densely-layered, and densely-packed artworks. The largest of them appear abstract from a distance, but they always have humorous figural elements, ranging from miscellaneous animals to subtle, collage-like faces and tiny graffiti figures, to fully achieved human forms. He often includes alphabetical components, as well as found objects such as coins, beans, pieces of wood, and tiny plastic objects. Linear elements and tiny cell-like structures evoke circuits and transistors that crisscross the energized surfaces of his paintings like electrical currents. García brushed, dripped, poured, cut, scumbled, and collaged his forms, then crowned them with glitter, before burying them in resin. They shine like other-worldly artifacts preserved in amber. He was an original, a visionary, an artist with an intuitive gift for constructing and connecting multivalent forms. San Antonio has lost a highly talented and unique creative force, one who never received the acknowledgment his work deserved.

****

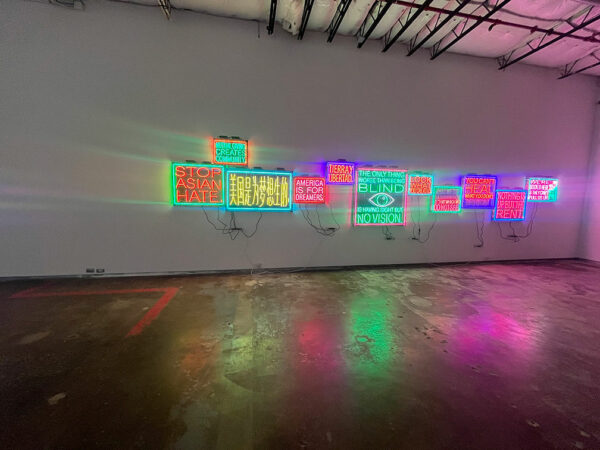

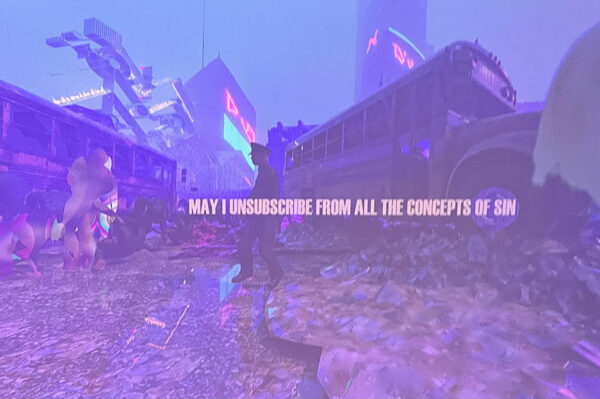

Patrick Martinez: Histories at Dallas Contemporary.

At the risk of invoking 2022 Harry Styles and his infamous “my favorite thing about the movie is that it felt like a movie,” Patrick Martinez’s Histories at Dallas Contemporary was everything you want an art exhibition to be. The multimedia paintings and installation works exploring the histories and evolving landscapes of Los Angeles and its Latinx culture were visually stunning, their neon and rubble commanding the sprawling industrial galleries of the museum. Histories was thought-provoking and surprising and let beauty and message be in service of one another. Prehistoric-looking vegetation, activist mantras, and nods to mural tradition seemed to speak to a primal human call to leave a trace of ourselves throughout time. Martinez and curator Rafael Barrientos Martínez created a show that reaffirmed the root joy of an exhibition — to be stirred by the pure act of looking.

****

Dario Robleto: The Signal at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth. Read the review here.

One of the most powerful and poignant exhibitions I saw this year was Dario Robleto: The Signal at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth. I was not very familiar with the artist’s work before, but I had a sense of what the main component of the show was about and I trusted that Curator Maggie Adler, who had brought other significant shows to the institution, was planning something monumental.

The show centered on Ancient Beacons Long for Notice, a new film by Robleto that investigates the making of the Golden Record and reveals what Ann Druyan snuck on the record. Listening to the story unfold over the 71-minute film was captivating. The imagery, a combination of archival photographs and video clips, perfectly supplemented the winding narrative. In the end, I had learned more about an important cultural moment but more importantly, I felt a strong sense of connection to the world, to the universe, to things that often feel unimaginably obscure.

In addition to the film, the rest of the exhibition was filled with an array of meaningful works that Robleto had completed between 2012 and 2018. I was impressed with the lines that his work straddles, both in terms of art and science, but also the space of playful and contemplative. After seeing the show, I had a chance to talk with the artist and gain more insight into his work, which I shared via this review.

Unbreakable: Feminist Visions from the Gilberto Cardenas and Dolores Garcia Collection at the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin.

I kicked off 2024 with a trip to Austin to learn more about the Mexic-Arte Museum. While I was there, I also popped over to the Blanton Museum of Art to see the outdoor spaces that had been renovated in 2023. Walking through the museum I stumbled upon Unbreakable: Feminist Visions from the Gilberto Cárdenas and Dolores Garcia Collection. Since the Blanton acquired more than 5,000 works from the Cárdenas/Garcia Collection, Claudia Zapata, Associate Curator of Latino Art, has been organizing small exhibitions that present different aspects of the collection.

The show featured works by Latina and Chicana artists exploring survival and resilience in the face of poverty, immigration, misogyny, and genocide. Many of the artists in the exhibition also had Texas ties, such as Liliana Wilson, Kathy Vargas, Suzy González, Margarita Cabrera, Sandra C. Fernández, and Delilah Montoya. The small but mighty exhibition left a lasting impression on me, as someone who worked in museums for a decade and saw firsthand the typical lack of representation in museum collections for Latina artists (and all women of color).

Celia Álvarez Muñoz: Los Brillantes at Ruby City, San Antonio (through January 19, 2025). Read our profile of the artist here.

Other than my hometown of Fort Worth, the city I spent the most time in this year was San Antonio. I was there multiple times as I researched culturally specific art organizations, but beyond that project I found myself drawn back to the city often to attend events and see exhibitions. As a photographer, I couldn’t pass up seeing Celia Álvarez Muñoz’s Los Brillantes at Ruby City, and I was honored to have an opportunity to interview her.

The exhibition showcases 18 photographs from Muñoz’s 2002 series Semejantes Personajes/Significant Personages, which documented Latinx artists in the city at the time. Using a Holga, Muñoz created multiple exposure images of the artists in their studios or other familiar spaces. After seeing the show and chatting with Muñoz at Ruby City, I was able to visit her studio in Arlington. There I got to see other works from the series and learn more about the artist’s life, resulting in an expansive profile covering much more than the current exhibition.

Julie Speed: The Suburbs of Eden at Ballroom Marfa (through February 2, 2025).

During this year’s Chinati Weekend, I made my way out to Marfa to participate in the festivities. While there is always much to see and do during this celebratory weekend in the small Texas town, Julie Speed: The Suburbs of Eden was a standout. Bringing together the artist’s work across decades and spanning the whole building of Ballroom Marfa, the exhibition transported me into the artist’s world. This was achieved in part through the inclusion of a participatory experience — Speed installed a work desk with materials, inviting visitors to write her a letter.

Speed’s work is beautiful and complex, reminiscent of both Surrealist and Renaissance works. Contorted figures and scenes of apocalyptic doom harken at once to humanity’s past and a disconcerting future. Somehow, the images are not horrifying, on the contrary, they are strangely serene, perhaps a reminder that we are all in this mess together.

Aside from the opportunity to see the exhibition, the weekend was made all the better when I accidentally intruded on Speed’s studio, thinking it was open to the public. Of course, she so generously welcomed me in and turned on the lights so I could peruse her space. We talked about photography, filming, and social media, and I was pleased to get a peek at her latest works in progress.

****

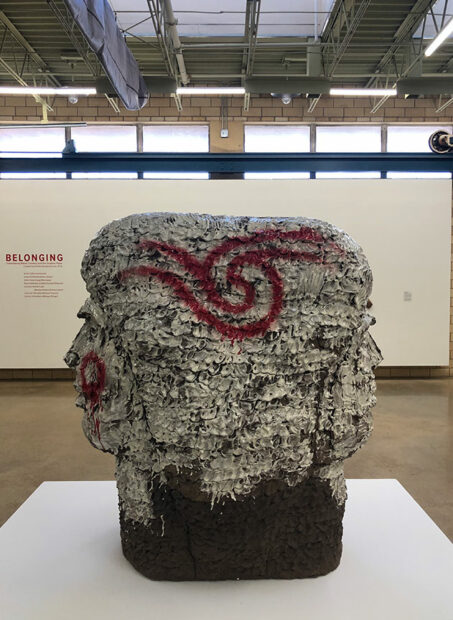

Raven Halfmoon (Caddo, Choctaw, Delaware, Otoe), “Red River Dreaming,” 2022, glazed ceramic, 55 x 53 x 35 inches. Collection of Historic Arkansas Museum, Little Rock. Courtesy of the artist and LHUCA.

Belonging: Contemporary Native Ceramics from the Southern Plains at the Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts, Lubbock.

This year, Lubbock’s art spaces have been the beneficiaries of some truly remarkable exhibitions of contemporary Native artists, courtesy of the scholarship and curatorial efforts of Klint Burgio-Ericson, backed by a Texas Tech University initiative to expand the curriculum and establish reciprocal relationships with Native communities in the region. Belonging at LHUCA featured ceramic works ranging from monumental, towering glazed ceramic sculptures by Raven Halfmoon (Caddo, Choctaw, Delaware, Otoe) to a constellation of tiny thumbprints of fired clay and blue glaze by Cortney Yellowhorse-Metzger (Osage). This very special exhibition, with works by the likes of Cannupa Hanska Luger (Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Lakota), Chase Kahwinhut Earles (Caddo), and Karita Coffey (Comanche), encompassed tradition and futurism in its sweep. The show took over most of the art center and was also accompanied by a ceramics symposium that was, frankly, revelatory for the conversation here in Lubbock. (I reviewed the show and symposium in Southwest Contemporary.)

Cara and Diego Romero: Bearing Witness to the Anthropocene at Landmark Gallery at the Texas Tech University School of Art, Lubbock.

Lubbock also found itself lucky enough to host the very first joint exhibition by Indigenous art stars and married couple Cara Romero (Chemeheuvi) and Diego Romero (Cochiti Pueblo). While their works in photography and pottery, respectively, differ greatly in aesthetic and material, curator Burgio-Ericson framed them successfully through their expression of Indigenous perspectives on the Anthropocene and its radical transformations of landscape. And the works’ arrangement complemented the Landmark Gallery space perfectly. A really beautiful and, again, special exhibition.

Abi Ogle: Metronome at the Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts, Lubbock.

I also want to throw in this exhibition that literally transformed LHUCA’s main hall. Abi Ogle’s dynamic kinetic installation Metronome took over the place, and, in the process, updated it into a contemporary white-cube exhibition space. With its 1,260-square-foot piece of white silk billowing overhead in a wave pattern driven by high-powered fans, Ogle’s piece necessitated that LHUCA’s (often inconvenient) firehouse-red wall, which had been intended as a permanent fixture, be painted — get this — white. This exciting development and ethereal exhibition were both unfortunately overshadowed by major drama at the time. But now that LHUCA has broken free of its signature red wall (not to mention the “burden of public funding” in one of the City Council member’s words), artists and curators can hopefully take full advantage of its spectacular, and now very versatile, turbine hall-like space.

****

Installation view of “Belonging: Contemporary Native Ceramics from the Southern Plains” with Raven Halfmoon’s (Caddo/Choctaw/Otoe/Delaware) Cowgirl at Heart and Cortney Yellowhorse-Metzger’s (Osage) Tho-day-they (To Live in Friendship)

Belonging: Contemporary Native Ceramics from the Southern Plains at the Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts, in conjunction with Texas Tech University, Lubbock. Read our review here.

In February and March 2024, the Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts, in Lubbock, hosted Belonging: Contemporary Native Ceramics from the Southern Plains. The exhibition, which was organized in conjunction with the Texas Ceramics Symposium, was curated by Klinton Burgio-Ericson of Texas Tech University’s School of Visual Arts. Featuring sculpture, vessels, and installations in clay, the show included the work of seven Native American artists, representing a dozen indigenous nations and communities. The theme of “belonging” explored the relational aspects of connectedness, as these ideas are tied to place, culture, time, memory, and kinship. Part of TTU’s “Expanding the Circle: Indigenous and Native American Studies” curriculum, Belonging served as a conversation toward strengthening relationships with the Native American communities of the South Plains. Collectively and individually, the show’s works also served as a reminder that we live in reciprocity with one another.

****

Carl Cheng / John Doe Co., “Early Warning System,” 1969–2023, fabricated plastic, electronics, projector mechanism, radio, wheat, wood. Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery. Photo: Jeff McLane

Carl Cheng: Nature Never Loses at The Contemporary Austin.

I just loved this show. I came to see some of the early photo work, got sucked in looking at an astounding collection of dried avocado husks, and really liked the public artwork that was shown with a projector. It’s hard to travel to look at public work in different locations, so to see multiple projects at once, with renderings, diagrams, and some in-process documentation, gave me a window into his thought process. Overall, the work was elegant, surprising, and energetic.

****

I know I’m just a large primate with a hypertrophied frontal lobe, but I know what I like. In what has to be a record year for censorship, I managed to see a good number of excellent exhibitions. Here are a few:

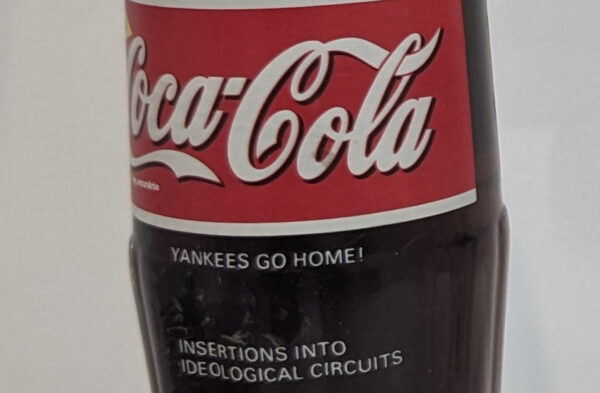

For What It’s Worth: Value Systems in Art since 1960 at The Warehouse, Dallas.

Easily the best group show I’ve seen in a decade, this large exhibition caught me off guard. I love a good curatorial premise; there are so few of them around anymore that it almost seems like an anachronistic concept in contemporary art. It’s rare to have a group exhibition get past the listicle stage of assembling a team of thinkers and makers. For What It’s Worth had an outstanding collection of artists who have created seminal pieces over the last sixty years. The artists in this exhibition address “the growing challenges to value systems that have arisen out of confrontations with social, political, and cultural power structures.” In other words, they do what I believe all art does: add value to the materials, ideas, and objects they encounter.

Thomas Demand: The Stutter of History at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

I first saw Demand’s work about twenty years ago when I was working as an art handler in the nation’s capital. I might not have registered what was happening in the innocuous prints had the collector not explained the work to me. Like other photographers from that time, such as Taryn Simon and Hiroshi Sugimoto, Demand creates work that pushed back against the truth claims of photography in a wholly unique manner. Images culled from a range of media are reconstructed to scale in paper and cardboard and then photographed in Demand’s studio. The resulting effect pushes the medium in new directions and asks viewers to consider both their relationship to images and photography’s role in constructing and circulating history. This show collected some of Demand’s major pieces from the last twenty-five years and had a room of new works drawn from phone photos. It was a gift to see so many of his projects collected together.

Phillip Pyle, II’s So Far So Good at the Houston Museum of African American Culture.

Laughing in a gallery is a rare engagement with art, especially when you’re laughing with the work. In the hands of Houston’s Phillip Pyle, II, comedy and satire are critical weapons. I wasn’t the only one who felt this as I wandered through So Far So Good — two other visitors had similar reactions to Pyle’s sense of artistic humor.

This show had a lot to say, but the way Pyle communicated the message made it one of my favorites of the year. He considers how ideas circulate beyond framed fine art. T-shirts, posters, and postcards are some of the systems the artist employs to build meaning. This was the strongest part of the show and reminded me of Legacy Russell’s amazing book Black Meme, which focuses on the history and politics of the circulation of Black culture, tracing the movement of the meme from its origins in silent film to its current state of endless digital reproduction. Pyle’s art reflects a world of comedy and pain to the viewer — a world in need of change. It’s rare to see art that covers this much ground and still has a punchline.

****

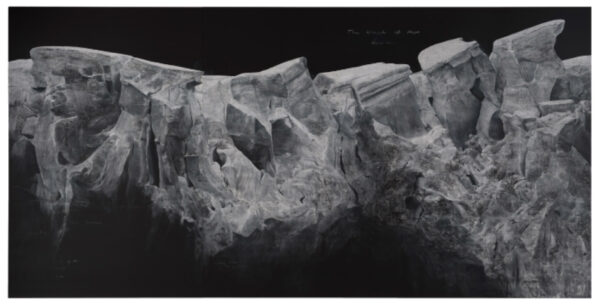

Tacita Dean, “The Wreck of Hope,” 2022, chalk on blackboard, 144 1/8 × 288 3/16 inches. Image

courtesy of the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery,

New York/Paris/Los Angeles. © Tacita Dean. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio.

Tacita Dean: Blind Folly at the Menil Collection, Houston (through April 19, 2025).

A 2024 art exhibition I continue to think about is Tacita Dean’s Blind Folly at the Menil Collection, curated by Michelle White. Dean’s works reward looking — beautiful, poetic, and often meditative. They are also rather tricky: belying complications and containing more, or new, meaning depending on your knowledge of her work. I am sure I missed some important ideas, but I think that might be Dean’s point. Her beautiful blackboards anchored the exhibition for me. In a time that feels impenetrably long yet abrupt and stupefying, the ephemerality of her works resonated and oddly felt reassuring.

Some other standout exhibitions this year: Ruth Asawa Through the Line at the Menil Drawing Institute, Meiji Modern: Fifty Years of New Japan at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and Edges of Ailey at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

****

Monica Martinez-Diaz: A Trajectory of Grief at Women & Their Work, Austin. Read our review here.

Grief is a tricky bitch. It’s a deeply personal and unique experience that is also a weirdly collective sentiment we can all share. In her exhibition at Women & Their Work, Monica Martinez-Diaz tackled this layered trickiness with a body of work that layered glimpses into memory through the stillness of her images — as if everything stopped the moment she clicked the shutter. Over the last year, life took me down a path of grief that was big, ungraspable, and exceptional and the memories I hold are like this show: still and locked in what feels like a series of unconnected moments.

Undercurrents: Vincent Valdez at Artpace San Antonio. Read our review of the Houston iteration of the exhibition here.

This show was originally exhibited at Art League Houston. The curator, Zhaira Constiniano, put together a superb show. In this iteration, the conference room of Artpace was converted into a dense, salon-style hang of work by formative mentors, educators, and colleagues of Valdez throughout his career. This show wasn’t just about Vincent as much as it was about everyone who contributed to his practice and formation as an artist. The exhibition felt like a homecoming, and it was as beautiful as it was generous. That said, Artpace is now obligated to a salon-style hang from here on.

Bernardo Vallarino: Size Matters-The Golden Rule and Carmen Menza: Patterns of Disturbance (through January 11, 2025) at Ro2 Art.

Both exhibitions are on view concurrently at Ro2 Art and this could not be a better programmatic choice on the part of gallery director Jordan Roth. Do not misunderstand, both exhibitions do not need to exist in tandem, they each have very distinct identities that are equally strong, powerful, and loud. Vallarino’s show is dark and decadent and tackles the fine line between power and kink, and one who judges and the other who is judged. Who gets to decide? Menza’s show is bright and light, taking on the fear and anger women feel about losing control of reproductive healthcare decisions. These shows individually are timely and strong, and together they are a force.

****

Host: Katarina Janečková Walshe at The Contemporary Austin. Read our review here.

During a year of great global strife, Katarína Janečková Walshe’s first museum show was a passionate plea for peace. In this energetic and ambitious exhibition, the artist — who immigrated from Bratislava, Slovakia to rural south Texas ten years ago — presented the compassionate model of motherhood as a balm for the increasing violence and discord around us. Her charged, multimedia artworks were intimate collaborations between herself and the elements that enter her life and studio, including her young daughter’s painted handprints and stray leaves stuck to her thickly impastoed paint. Nature, power, sensuality, and care moved across Janečková Walshe’s large-scale canvases and sculpture. Altogether, the exhibition revealed an innovative artist with a profound message to share.

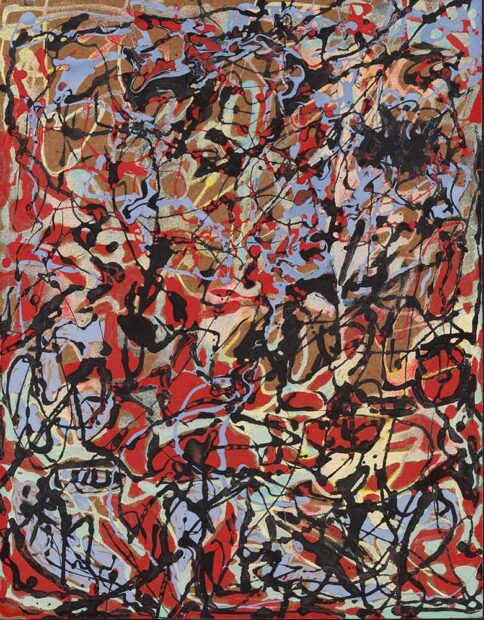

Janet Sobel, Untitled, ca. 1946–48, enamel and sand on board, 17 5/16 × 14 inches. The Menil Collection, Houston, Gift of Leonard Sobel and Family. © Janet Sobel. Photo: James Craven

Janet Sobel: All-Over at the Menil Collection, Houston. Read our review here.

Named America’s best woman painter by Peggy Guggenheim and considered the likely inspiration behind Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, Janet Sobel rocked the New York art world in the 1940s and then promptly disappeared (or so it seemed). This thoughtful exhibition at the Menil Collection gave visitors a rare glimpse at the artist’s groundbreaking paintings while contesting the problematic ways that Sobel and her work have historically been received. The artist’s mixed media abstractions broke the mold — Clement Greenberg called them “the first really all-over effect that I had seen” — but so did her back story. A Jewish immigrant and mother of five, Sobel began painting without formal instruction at age 44. Labels like “naive” and “primitive” were imposed on the artist in her day, but this exhibition gave Sobel’s important but misunderstood place in art history a second look.

****

Eileen Maxson: Parent Trap at Keijsers Koning, Dallas. Read our review here.

Eileen Maxson’s three-channel video installation, presented at Keijsers Koning in Dallas during late summer 2024, tackled the fraught terrain of contemporary American politics through the deeply personal lens of family. Featuring her parents as both subjects and commentators, the work offered an incisive critique of the performative and cyclical nature of political discourse in a polarized two-party system.

The gallery became a sparse environment for this showing. A false wall bisecting the space served as both a physical and conceptual metaphor for the emotional and ideological divides that typify political engagement today. The minimalist setup focused the viewer’s attention entirely on the interplay between the three video screens, creating a sense of intimacy and isolation that mirrored the insular effect of modern political opinion-making.

Through poignant exchanges, the videos revealed the tensions and contradictions inherent in Maxson’s intergenerational dialogue with her parents. These interactions served as a microcosm of the national landscape, examining how political ideologies are shaped by lived experiences, personal histories, and media narratives.

As one of the most affecting exhibitions of the year in Texas, Maxson’s work at Keijsers Koning demonstrated the power of art to distill complex sociopolitical phenomena into intimate, resonant experiences. It left audiences grappling with questions about the porous boundaries between the personal and the political, making it an essential entry in the state’s 2024 cultural landscape.

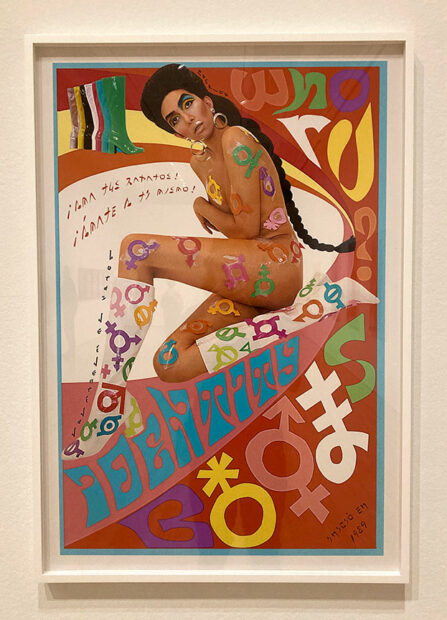

Martine Gutierrez, “Identity Boots Ad,” page 99 from “Indigenous Woman,” 2018, archival pigment print

Native America: In Translation at the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin. Read our review here.

Curated by Wendy Red Star, this exhibition presents a rich dialogue on Indigenous identity through the lens of photography and mixed media. Featuring an array of artists including Martine Gutierrez, Alan Michelson, Guadalupe Maravilla, Marianne Nicolson, Nalikutaar Jacqueline Cleveland, and others, the show dismantles stereotypes and repositions Indigenous narratives within contemporary contexts of self-representation and resilience.

Highlights include Gutierrez’s fashion-inspired Indigenous Woman series, which reclaims beauty standards through an Indigenous gaze, and Michelson’s projection work, blending historical memory with cultural symbolism. Cleveland’s documentation of Yup’ik foraging traditions emphasizes sustainable practices tied to land stewardship, while Nicolson’s luminous glass installations evoke the fragility and endurance of cultural identity.

Through these varied works, Native America: In Translation challenges the exoticism often imposed on Indigenous art, reframing it as a living, evolving practice that bridges the past and present. This exhibition underscores the complexity of cultural translation and offers profound insights into the layered realities of Indigenous life today.

The Legacy of Vesuvius: Bourbon Discoveries on the Bay of Naples at the Meadows Museum, Dallas.

This exhibition dives into the Bourbon monarchy’s transformative excavations of Herculaneum and Pompeii, revealing how these archaeological endeavors shaped the neoclassical aesthetic that swept through 18th-century Europe. Through frescoes, Capodimonte porcelain, court portraits, and other artifacts, the show highlights the fusion of political ambition, cultural revival, and the enduring fascination with sites of catastrophe.

The Bourbon rulers used these excavations to elevate their prestige by drawing parallels between their reign and the grandeur of ancient Rome. The exhibition reflects on this strategic alignment of art and power while presenting rare and delicate works, some of which may never leave Naples again. Visitors are invited to ponder the dual symbolism of Vesuvius as both a destructive force and a muse for artistic and cultural renewal, bridging themes of nature’s volatility and human resilience. A compelling narrative of disaster and creativity, this exhibition offers an exceptional glimpse into the intertwined legacies of history, politics, and art.

****

A view of Shazia Sikander’s “Havah… to breathe, air, life”

on the University of Houston after it was beheaded

Shazia Sikander’s Havah… to breathe, air, life at the University of Houston.

How many of us say we want our creative work to do something in the world? The view from the Roy Cullen Building at the University of Houston, where my office and classes are located, was an up-close look at the variety of conversations, actions, and array of feelings a piece of art can activate. From the confusion many of us in the English department had when the statue was first erected to the immediate and troubling demonstration from an anti-abortion group unrelated to the University of Houston system, which triggered conversations in both the Art Department and the Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies program. Our somewhat secluded campus became part of one of the biggest national news stories in the art world when Havah… to breathe, air, life was beheaded in July. Sikander designed Havah… to breathe, air, life to represent “the history of public works, from which women and people of color have largely been absent” and the anti-abortion response revealed a massive disconnect in how different groups interpret art and the responsibility we have to interpret “representations of women” accurately and justly. The face of Havah… to breathe, air, life was modeled after numerous women poets from historical periods and the contemporary moment. In a testament to the intricacies of Havah… to breathe, air, life, more resonances emerge as that head fell mere feet away from the English department building.

Jacolby Satterwhite’s A Metta Prayer at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

In 2023, when Satterwhite’s piece We Are in Hell when We Hurt Each Other showed at the Blaffer Art Museum, he instantly became one of my favorite artists working today. This eclectic mix of video game aesthetics, vogueing, and music, that resonates with Satterwhite’s identities as an African American person and a gay man has such wildness and depth, that it could only come from a singular imagination. A Metta Prayer brought Satterwhite’s work back to Houston on a bigger scale. Its immersive four-panel display — the synthesis of Eastern spiritual traditions with Southern gospel — shows the path to a better future, in spite of historical and structural violence. In a time when we often feel the rift between the ecological and digital worlds, A Metta Prayer celebrates the moments when we can inhabit both.

****

American Cowboys at the Briscoe Museum of Western Art, San Antonio.

American Cowboys strips cowboy culture of Hollywood-written mythologies through 100 black-and-white photographs. The exhibition reached not for stories of valorous cowboys, wild brawls, or the enchanting landscape but for modern people who inhabit the region. It was a chronicle of professional pickup riders and ranchers in the ring and on the town. With her camera in hand, the New York City-based French photographer Anouk Masson Krantz crossed the plains and gullies of the American Southwest and kept the locals’ routines, learned their rituals, and felt the adrenaline of rodeoing and ranching, all which came through her portraits and landscapes.

****

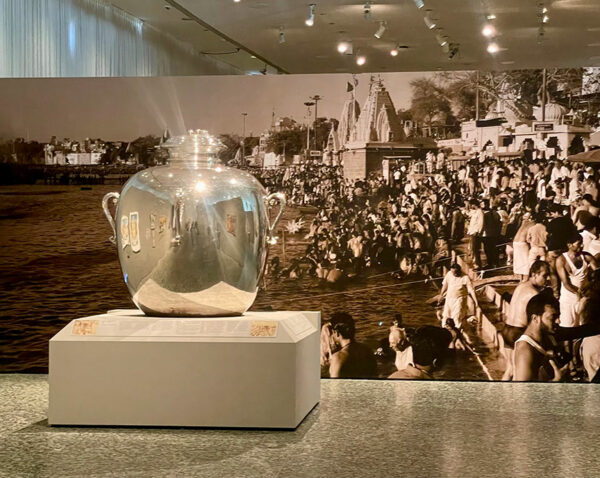

Gangajali (Silver Water Urn), Jaipur, 20th century, silver, Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum Trust. Photo: Donna Tennant

Living With the Gods at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Read our review here.

The MFAH has really stepped up in the past few years, but this exhibition of 200 objects created in more than 4000 years stands out. Director Gary Tinterow convinced British art historian Neil MacGregor to come out of retirement to curate this show. Unprecedented loans from the great collections of the world, including the Prado, the Maharaja of Jaipur, and the Holy Monastery of St. Catherine in Egypt are displayed in dialogue with works from the MFAH collection. The exhibition, which is named for MacGregor’s BBC radio series and book of the same name, fills 10 galleries, each with a different theme: The Cosmos; Light, Fire, and Flame; Waters of Life; Helpers and Protectors; Living with the Dead; Life of Christ; Life of Buddha, Living with the Word, the Body of a God, Sharing Food; and Pilgrimage. On display is one of the largest silver objects ever created, the Gangajali, which was made to hold the divine water of the Ganges (when full, it weights four and a half tons). There are leaves recently gathered from the Burning Bush, an eagle Kachina figure, and much, much more.

Nancy O’Connor, “I Couldn’t Hear Nobody Pray,” 2024, framed photograph and audio recording, 43.5 x 67.5 x 4.5 inches

Nancy O’Connor, Welcome Table, at Barbara Davis Gallery, Houston.

Nancy O’Connor was raised on a ranch near Victoria, Texas, and became friends in her teens with Spencer Cook, her family’s cook. He had been part of a community of Black cowboys who worked the ranches in the Luis Bend area along the San Antonio River. When Cook died, O’Connor attended his funeral at the Greater Zion Baptist Church, a small church that was a gathering place for the cowboys and their families. Welcome Table refers to the long table that the artist borrowed for this exhibition, which was still inside the now-empty church. O’Connor was only 19 when she first met those who attended the church, but she knew instinctively that she was witnessing a way of life that would soon disappear. A film and photography student, she began documenting the lives of those in the community. This show included just a fraction of the interviews, photographs, artifacts, and videos that O’Connor has collected and created since 1976. Everyone pictured in the exhibition has now passed on, so it offered a poignant glimpse into those who worked the cattle that grazed the vast prairies of South Texas.

****

Julie Speed: The Suburbs of Eden at Ballroom Marfa (through February 2, 2025).

When I showed up to photograph the opening of Julie Speed’s The Suburbs of Eden at Ballroom Marfa, the gallery was packed with members of the local community. The Suburbs of Eden provides an extensive retrospective of Speed’s decades-long career, featuring over 70 works of her surreal, dream-like paintings, collages, and gouaches. Each gallery space requires time to explore the different styles and themes in her work, but this show to me was a beautiful reminder that some of the most prolific people you’ll meet are your neighbors.

Exhibition Nowhere no. 0001 at Club Nowhere, Marfa.

The new exhibition space, Club Nowhere, debuted during Chinati Weekend with its DIY ethos and an art show featuring 14 artists who live and work in Marfa. There were all types of mediums displayed around the old adobe home that made exploring every nook and cranny feel like a treasure hunt. Rhonda Manley’s large oil paintings welcomed guests in the hallway next to Mo Eldridge’s structures made of fiber and wood. Tina Rivera’s beaded flowers were on display on the kitchen counter, while Shea Carley’s paper pulp painting on silkscreen hung from the carport in the backyard. The light from the West Texas sunset painted Natalie Melendez’s mixed media collages and Jax Le Baron-Widmar’s wood paintings in the front room with bold golden hues, bringing a new and beautiful perspective to the pieces.

****

Eric Schnell’s The Island of The Umbellifers (Part II) at The Old Jail Art Center, Albany. Read our review here.

Eric Schnell’s The Island of The Umbellifers (Part II) was a sprawl of collaged blocks, shaped plywood sections, and wall drawings that inhabited three spaces at The Old Jail Art Center. The composite parts worked together to illuminate our capacity for altruism and generosity. The utopic nature of Schnell’s installation was underscored by his reference to umbellifers, a family of flowering plants that attract predatory insects in order to remove aphids and other pests.

The unique qualities of umbellifers benefit themselves and other surrounding plants. By extension, our own acts of kindness are subversive, non-transactional, and political. The good things we choose to do for others are what shape the world for the better.

****

Kristen Cochran, “Laundry Day,” 2024, Rockite cement, old clothes, and steel rack, 55 x 72 x 44 inches. Photo: Fernando Alvarez

Tailgate at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.

The Curators of Education at the Modern inaugurated Tailgate on August 16. The one-day pop-up exhibition showcased twenty artists working in education as sculpture and new media instructors in Texas. As an art education grad student, it was a heartwarming experience to witness these artists and educators’ passionate and collaborative work. The show was put on in the museum’s parking lot and consisted of many interactive experiences and works that play with the concepts of adaptation, fandom, ritual, and community. This was easily the most fun I have ever had at an exhibition fitted with an ancient Whataburger archaeology dig site, gigantic fake museum ID badges, a tricked-out survival camper, and merchandise, including a Tailgate branded university-style banner and koozie. And, as the day faded away, in the distance, guests could hear the faint rumbling echoes of a football game just down the road, providing an on-theme ambient sound to veil the show.

Jason Dann, “The Racer,” 2016, oil, acrylic, and charcoal on canvas, 84 x 60 inches. Photo: Jessamine

Jason Dann: Dream Diary No. 3 at Jessamine, Dallas.

In the last year, the iconic and presumably abandoned Belmont Hotel has repurposed its derelict hotel rooms into an artist-run gallery headed by Greg Meza and Oshay Green. This fall, Jessamine invited University of North Texas alum Jason Dann to exhibit an assortment of his paintings and books. At the opening reception, I watched Dann and his partner launch Beyblades into an acrylic arena, playfully celebrating the artist’s first solo exhibition. Primarily capturing his own likeness in his paintings, Dann presents his figures composed within enigmatic spaces, often exaggerating their form and movement by playing with color, light, and shadow. In The Racer, Dann fuses representational components with abstraction, layering a technicolor palette of paint atop a nondescript sports car surrounded by sheer sketches that reveal what appears to be an anthropomorphized vape, a mosquito chasing a fly chasing an airplane, a suspiciously limp and long finger, a mechanism of horns, chains, gears, and brakes, a dog bone, and several brewskis.

****

Installation view of “Secuelas, cuerpo, tierra, y mar.” Courtesy of the artist and Jane Lombard Gallery. Photo: Arturo Sanchez

Margarita Cabrera, Secuelas: cuerpo, tierra, y mar at Jane Lombard Gallery, New York City.

Full disclosure: I introduced the Texas artist to the New York gallery a few years ago, so I may be a bit biased. But El Vaivén del Mar, the centerpiece of Margarita Cabrera’s terrific show bowled me over with its deceptively lighthearted deployment of incongruous materials to serious ends. A soft-sculpture Spanish galleon, sewn from her signature material of olive-drab US Border Patrol uniforms, floats on a sprawling sea of the colorful ruffles of skirts from flamenco costumes. A playfully simple gesture, and an equivocal one, it nonetheless speaks of the long shadow of history the double-edged sword of “heritage,” and how the legacies of colonial structures and the exploitations of capital ripple from the Age of Exploration to wash up on the shores of the present.

****

Ruth Asawa Through Line at the Menil Drawing Institute, Houston. Read our review here.

This exhibition demonstrated that in addition to being a master sculptor, Ruth Asawa was a meticulous draftsman. I was particularly taken with her pseudo-print pieces, which included monoprints of a leaf and of a fish (a gyotaku print), potato prints, and works made using rubber stamps. It is rewarding for Asawa to get her full due; thanks to this wonderful, thorough show co-organized by the Menil and the Whitney Museum of American Art, our recognition of her as an all-around artist is happening in tandem with her rise in the art world’s consciousness. Her drawings are raw and real. Contradictingly, they make daily life look both imperfect and idyllic. Through Line was a show that thoroughly examined and took seriously what it means to be an artist looking at the world.

Iva Kinnaird, “TV Guy,” 2024, acrylic on cockroach, aluminum hardware. Image courtesy LAURA © Graham W. Bell

Arm Candy: Iva Kinnaird & Emily Peacock at the San Jacinto College South Campus Gallery, Houston.

Among Houston’s artists who are mining the complexities of humor, Iva Kinnaird and Emily Peacock are queens. From hot dog jokes to painted cockroaches to new photo experiments, the pair’s two-person show took (and landed) many big swings. It would seem to the naked eye that the duo’s works are too disparate to form a cohesive show, but when jumbled up in a room, I had to consult the checklist about which piece was whose. In reality, it worked because both Kinnaird and Peacock have practices that visually jut in different directions (from each other but also from their own paths), but always remain true to their core. Putting into words what exactly about the exhibition worked, or even why it was funny, is like trying to explain calculus to a donkey: you can make an effort, but you’re just going to fail no matter how hard you try.

Installation view of “Vincent Valdez: Just a Dream…” at Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, 2024. Photo: Peter Molick.

Vincent Valdez: Just a Dream… at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (through March 23, 2025).

I believe that one of the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston’s major roles in our state’s art ecosystem is to put on high-quality, well-funded major exhibitions examining the work of deserved Texas artists. This show, which is Vincent Valdez’s first major survey, does just that. Featuring over 20 years of work — including a flat-file-filled and salon-hung room overflowing with early pieces, prints, production drawings, and more — the exhibition makes a case not only for a serious national consideration of Valdez’s practice, but also for the wider visibility of Latino and Mexican-American artists and issues. The fact that the show is co-organized by the CAMH’s Patricia Restrepo and Denise Markonish from MASS MoCA, and that it has a major catalog, is significant: exhibitions like this need to travel and have a longer life in order to really make a splash. I hope and believe that this show is yet another marker on the long road to Texas, its artists, and its institutions being seen as serious, talented, and the best of the best.

A selection of very honorable mentions, in no particular order: For What It’s Worth: Value Systems in Art since 1960, a staggering group show at The Warehouse in Dallas; the Asia Society Texas Center’s group moon shot of a show, Space City: Art in the Age of Artemis; exhibitions by Jess Johnson and Jeff Williams at Co-Lab Projects in Austin; Guillermo Gómez-Peña and Balitrónica’s performance at Fusebox Festival; James Sterling Pitt’s wacky, bright ceramic structures at Seven Sisters in Houston; Juan de Dios Mora’s crazy Los Tremendos linocuts at Ivester Contemporary in Austin; Jeffrey Dell’s monoprints at the Flatbed Center For Contemporary Printmaking in Austin and his new screenprints at David Shelton Gallery in Houston; Houston taking over the ADAA’s Art Show in New York City; Rackstraw Downes’ perennial landscapes at Texas Gallery in Houston; Raqib Shaw’s meticulously, jewel-like paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Tracye Wear’s living ceramics at Moody Gallery in Houston; JCA’s poppy paintings at Anya Tish Gallery; Joey Fauerso’s Texas takeover at Wrong Marfa and David Shelton Gallery in Houston; Cody Ledvina’s weird wonders at Pablo Cardoza Gallery in Houston; Rick Lowe’s showstopping exhibition at Museo di Palazzo Grimani in Venice, Italy; Pictures from Home at the Alley Theatre in Houston; Leslie Wilkes’ subtle paintings in The Edge of Memory at Rule Gallery in Marfa; the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft’s wonderful Designing Motherhood exhibition; Katharina Grosse’s loopy paintings at Hetzler Marfa; Do Ho Suh’s collections at the Moody Center for the Arts in Houston; Annette Lawrence’s somber paintings at Conduit Gallery in Dallas; Living With the Gods at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Shahzia Sikander’s public art saga at the University of Houston; Sarah Sudhoff’s somber video at grayDUCK Gallery in Austin; James Surls’ monumental sculpture at the UMLAUF Sculpture Garden and Museum in Austin; Raychael Stine’s magical paintings at Cris Worley Fine Arts in Dallas; Christopher Blay’s Ritual SpLaVCe at the Galveston Arts Center; remembering Frank X. Tolbert 2 at Andrew Durham Gallery in Houston; Cindi Holt and Susie Phillips’ bright worlds at the Tyler Museum of Art; the group show to end all group shows at Basket Books & Art in Houston; and Tacita Dean’s survey at the Menil Collection in Houston.

Read our Best of lists from previous years below:

—Glasstire’s Best of 2023

—Our Favorite Art Books of 2023

—Glasstire’s Best of 2022

—Our Favorite Art Books of 2022

—Glasstire’s Best of 2021

—Our Favorite Art Books of 2021

—Glasstire’s Best of 2020

—Glasstire’s Best of 2019

Recent Comments