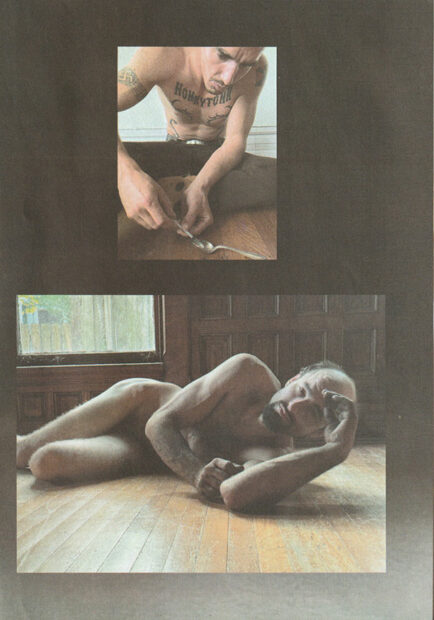

Editor’s note: The images in this review depict drug use, gunplay, and nudity.

I sat at my desk the day after the election, still reeling from the news. I wonder what the point is in writing about art during this moment in U.S. history. I checked social media and amongst the garbage and found two gems, both posted by artists. Language artist and A.I. researcher Sasha Stiles posted a quote from Toni Morrison:

This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.

Latina artist and college dean Dr. Lupita Murillo-Tinnen posted the 2nd quote by Venice Williams. I won’t reprint it in its entirety here, but it’s worth a read on her Facebook page. 37,000 people shared it within a few hours, so I’m not alone in my thoughts. To paraphrase, she encourages folks to continue to do the work, lead with compassion, dismantle broken systems, and do so in the name of community, partnership, and collaboration. The words were exactly what I needed to motivate me to get to work.

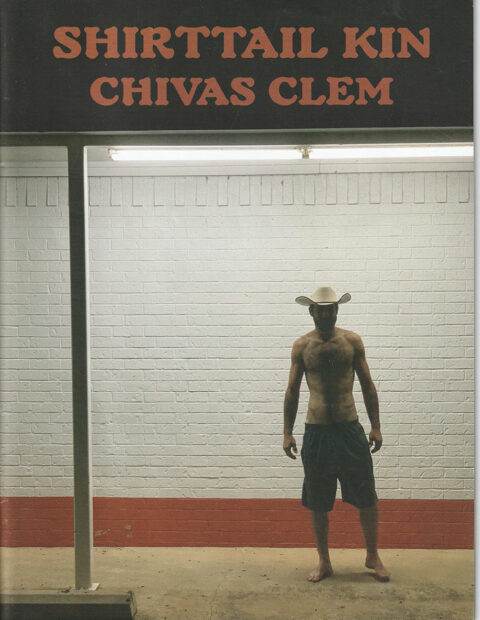

In thinking about the importance of Chivas Clem’s photographs in this post-election haze, the work speaks to visibility, humanity, and the importance of community and collaboration. The Paris, Texas artist presents a decade of photographic portraits depicting a community of local, transient men whom he befriended and subsequently collaborated with.

Much has been made of the fact that Clem left an illustrious New York art career to return to his hometown. The press release states that it was a “radical” move to return to Texas. I find it odd and off-putting that a move to Texas would be considered radical. This infers that New York is the be-all, end-all place for artists and Texas is some sort of cultural wasteland (as was suggested to me by New Yorkers when I moved to the state twelve years ago). Why wouldn’t an artist want to enjoy vast blue skies, open landscapes, lower cost of living, fewer people, and less noise? That sounds like a recipe for creativity to flourish.

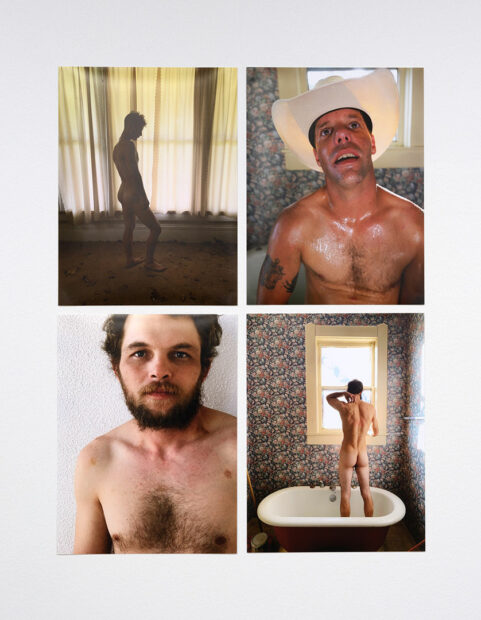

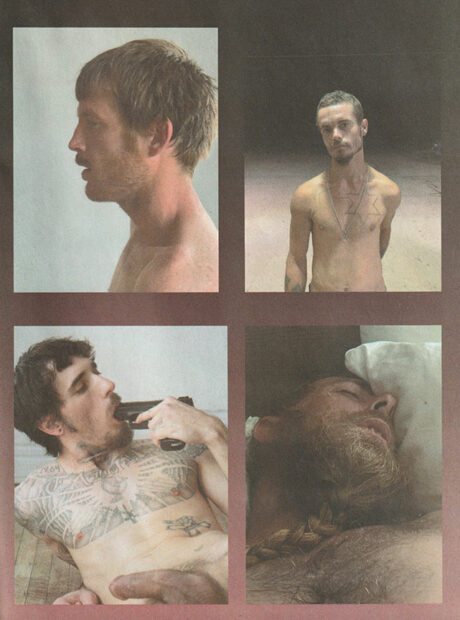

As I look at Clem’s photographs, the words desire, trust, vulnerability, intimacy, and comfort in one’s body come to mind. The images are sexy and gritty. They also speak to larger themes of dismantling the cowboy trope, the results of the prison-industrial complex, the epidemic of opioid addiction, and the disintegration of the farming industry leading to poverty and joblessness.

Unlike traditional photographic standards, the images are not matted or framed. The decision to mount borderless images directly on the wall “de-rarifies” the photograph as a fetishized object. The absence of glass strips away the separation and formality between the viewer and subject. The choice to print the catalog as a zine, rather than a glossy hardcover monograph also contributes to the de-rarification of the subject and provides an affordable option for visitors.

It was difficult to choose which images to discuss since there are so many that are evocative. I found myself returning to the larger vertical images such as Rudy Smoking II and Harley with a Hermes Scarf. Both men stare defiantly at the camera with a confident ease and posturing of their bodies. I can’t imagine ever feeling that comfortable in my own body.

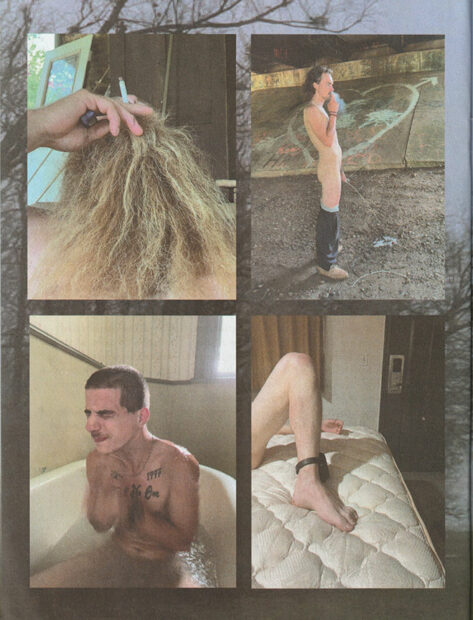

I was also drawn to the images of hands such as Jer Eating Catfish with Dirty Hands. The eye first travels to the dirt-encrusted fingernails which speaks to hard labor, and then rests upon the illuminated divot in Jer’s collarbone. The duality of beauty and grit inherent in the photograph is a strategy found in many of Clem’s images. Game Over shows a close-up of two hands with a single letter on each finger, together spelling game over. While this could be a reference to prison, it addresses a larger issue of hopelessness for the future. The only direct reference to incarceration is Red River Motel which features a leg wearing an ankle monitor on a bare mattress. It is also one of the few images that does not identify the subject’s name.

In reading about this series, Clem’s work is often compared to Larry Clark’s images. While I understand the comparison (I assume that it refers to Clark’s Tulsa series), it seems a superficial comparison at best. Yes, they are both photographing marginalized communities with drug use and guns. However, their style is very different. Clark always maintained a clinical, dispassionate distance from his subjects, which he was heavily criticized for. Also, Clark’s work emphasized drug use, so that it overshadowed his subjects. Clem’s photographs allude to drug use, but none of the exhibited photographs show it explicitly. The zine/catalog has a few edgier images such as Jason Shooting Dope and Aaron Eating a Gun with Erection. The men in Clem’s photographs are always the focus of the composition, rather than their actions or their props.

Hilton Als writes a short essay about Chivas Clem’s work in which he speaks about the importance of place, how the portraits reference southern history, specifically the wound of southern history, but also a queer world that is rarely seen. Clem does not try to hide or whitewash this history away. The homoerotic tension in the photographs is combined with a tenderness and affection not often portrayed in images depicting masculinity.

I return to the question of why Clem’s work is so important. When you Google Paris, Texas, besides the fake Eiffel Tower attraction, the town is known for friendly locals. I find this ironic, since as a queer youth Clem was treated as an outcast, experiencing discrimination. Unfortunately, this is a reality throughout Texas and many places in the south. Returning to a homeland that was openly hostile to him as a child and creating portraits that make visible what has been invisible is an act of courage and defiance. In a state that is actively trying to revoke LGBTQ rights, it is important to have the work seen. The exhibition title Shirttail Kin is a southern term that refers to one’s honorary relatives. Artists have always chosen their own communities and Shirttail Kin reflects Chivas Clem’s commitment to community and his chosen family.

Chivas Clem: Shirttail Kin is on view through January 12 at Dallas Contemporary.

Recent Comments