The audience never knew what to expect when it came to Les Ballets Russes. In the summer of 1913, the company made itself notorious by throwing pre-war Paris into a riot. Vaslav Nijinsky, who was known as the company’s androgynous lead male dancer, choreographed Igor Stravinsky’s radical The Rite of Spring (le Sacre du Printemps) in what had seemed like the most radical way possible: flouting all the rules of ballet and defying Parisian hopes for another exuberant Russian opera. Instead, Paris did not even catch a glimpse of the popular dancer and descended into an insult-throwing and, if the myths are to be believed, fruit-throwing chaos. Time, legend, and the ongoing Great War made the premiere of The Rite of Spring seem an eternity away, but the London performance of The Sleeping Princess (in truth, a Ballets Russes adaptation of Tchaikovsky’s landmark Sleeping Beauty) brought back some of the names behind The Rite of Spring: Igor Stravinsky, Russia’s revolutionary composer; Sergei Diaghilev, founder and impresario of Les Ballets Russes; and B. Nijinska, choreographer. One letter separated the Nijinska from that of the Continent’s most subversive dancer-choreographer, but in truth, Vaslav Nijinsky could not have been closer. His younger sister, Bronislava Nijinska, was making her debut as choreographer for Les Ballets Russes. While the London premiere of The Sleeping Princess would not result in a riot, it nevertheless would launch the career of a generation of Russian women artists who would help remake ballet for the twentieth century.

The McNay Art Museum’s ongoing exhibit, “Female Artists of Les Ballets Russes: Designing the Legacy” (running through January 12, 2025) brings to the fore not only the twentieth century’s most important dance company, Les Ballets Russes, but also the female artists who worked behind the scenes to make Les Ballets Russes a force for musical and artistic modernism. Consisting of costumes, posters, scores, set designs, shoes, and memorabilia, “Female Artists of Les Ballets Russes” showcases the visual richness of an art form that was on the cutting edge of the visual, moving, and musical arts like nothing else. In the two decades in which Les Ballets Russes danced across Europe and the Americas (1909-1929), ballet was a labor-intensive art form that tried to mount immense productions. Musicians, conductors, female ballerinas, male danseurs, and stagehands were only the front end of the production. Behind the scenes, choreographers, dancing masters and dancing mistresses, costumiers, set designers, composers, and directors made the vast productions of Les Ballets Russes possible. In the exceptionally well-studied history of Les Ballets Russes, the men who were behind the scenes—names like Diaghilev, Bakst, Stravinsky, Nijinsky, and Balanchine—take on the patina of a latter-day Dionysus, Prometheus, or Orpheus. The heroic narratives of Les Ballets Russes have often focused on the famous men at the expense of the women who also designed, choreographed, and sewed to make the lavish and radical productions of Les Ballets Russes possible. With “Female Artists of Les Ballets Russes: Designing the Legacy,” organized by curators Caroline Hamilton, Remus Moore, R. Scott Blackshire, and Kim Neptune, the McNay presents a long-awaited opportunity to revisit the heroic male-centered narrative of the history of ballet, all the while reminding visitors how rich and supple an art form the ballet of a century ago was.

The name “Les Ballets Russes” (“The Russian Ballets”) says it all. A nominally European art form, ballet, that grew out of the seventeenth palaces in Italy and France, combined with the influence of Russian culture. When Sergei Diaghilev (1872-1929) founded Les Ballets Russes in 1909, the Russian Empire was at its peak cultural influence. The Russian novelists and plays were translated into the European languages, Leo Tolstoy was as much a literary and spiritual phenomenon in Paris and London as he was in St. Petersburg. Russian composers like Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) and Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908) had transfixed European audiences like nothing else had since the 1883 death of Richard Wagner. For the urbane elite of the great European cities, Russian literature and music beckoned with the appeal of the Other—different moral sensibilities and musical motifs that shook European audiences out of complacency and verged on the exotic. Russian ballet was no different.

Sergei Diaghilev, who grew up in a late Russian Empire that always looked toward Europe, saw in the Russian ballet tradition an opportunity both to shock Europeans out of Belle Époque complacency, as well as to realize Richard Wagner’s artistic ideal of Gesamtkunstwerk: a complete work of art that united the visual, the musical, and the physical arts. Under Diaghilev’s two-decade leadership, Les Ballets Russes fascinated and shocked international audiences with a Ballet that looked east and west at the same time. Les Ballets Russes remained grounded in Russian and Eurasian musical and visual traditions that Diaghilev together with his greatest musical collaborator, Igor Stravinsky would mine in defiance of three centuries of European musical canons. Les Ballets Russes faced the West, not only to the audiences in Paris and London but also to the upheavals in visual art taking place in the Paris of the early twentieth century and to the upheavals in thought that came with the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche and Sigmund Freud. Les Ballets Russes brought to Europe art that both sought out the European aristocracy and bourgeoisie as an audience, titillated those audiences with the promise of “Eastern” exoticism, and then shocked them with harsh music, sensual body movements, and stories—like the atavistic human sacrifice in Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring—that were simply unfit for polite society. This potent combination made Les Ballets Russes thrive.

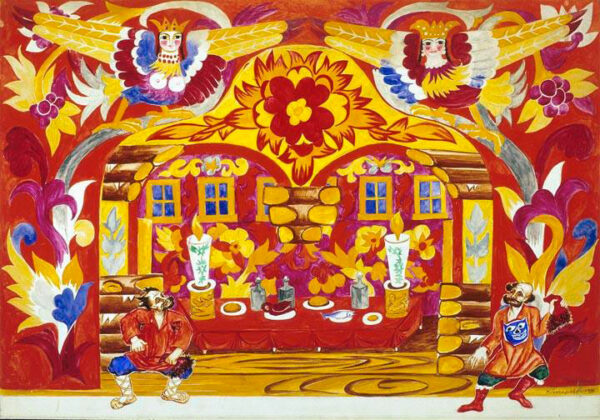

While almost no recordings of Les Ballets Russes on tour or in rehearsal survive, a rich visual archive has come down. Thanks to Diaghilev’s fraught relationship with his homeland after the 1917 October Revolution, Les Ballets Russes became an expat artistic company: its influence and its records dispersed across the world. Thankfully for Texans, the McNay Museum and the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin are two of the best repositories for Les Ballets Russes: and both cultural repositories contribute to “Female Artists of Les Ballets Russes.” The McNay’s curators have been able to select and display costumes and set designs that showcase Les Ballets Russes at its most sumptuous and most ambitious. The rich sampling of costumes (many of which are preserved from the first performances a century ago), display the theatrical power of Les Ballets Russes. There is not a tutu or leotard in sight. For 1921’s Sleeping Princess, Bronislava Nijinska choreographed dancers to pirouette and leap in eighteenth-century period costumes designed by her Ballets Russes collaborator, Natalia Gontcharova. The set designs likewise defied traditionalist expectations. Gontcharova’s design for the curtain of The Golden Cockerel (Le Coq d’Or) throws traditional Renaissance foreshortening to the winds, in preference for squatted men who look like they walked out of illuminated medieval Russian manuscripts, and a palette of rich reds and yellows that would have been the envy of Matisse or Chagall.

Natalia Gontcharova, curtain design for the prologue of “Le Coq D’Or (The Golden Coquerel),” 1913, watercolor and collage on paper, 19 x 27 inches

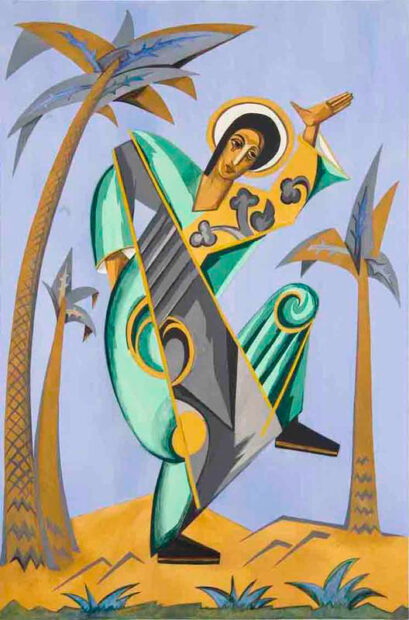

More than any other female artist represented in the show, Natalia Gontcharova (1881-1962), exemplifies the artistic ambitions of Les Ballets Russes. Her designs look east toward Russian visual motifs—especially Russian art’s foundations in iconography—and toward the foment in European art of the early twentieth century. The exhibit’s final gallery shows Gontcharova’s work on the Ballets Russes production of The Golden Cockerel, adapted from the late nineteenth-century opera by Rimsky-Korsakov, making just how clear how extensive her contributions were. Gontcharova saw herself as a maker of Gesamtkunstwerk. Her painted set designs complement the massive costumes that she also designed—dresses and robes with long trains, evocative of medieval Russia, pre-Europeanized Russia that look impossible to dance in. Some of her costume designs, like that of the quasi-Cubist Apostle John in Liturgie for an unproduced ballet, simply look impossible to realize. Gontcharova would go on to join the other members of Les Ballets Russes who lived in exile from the Soviet Union, yet her visual inclinations make her a formidable parallel to other Eastern European and Russian artists, like Marc Chagall or even Wassily Kandinsky, who continued to practice art. Gontcharova is worthy of an exhibit on her own terms.

“Women Artists of Les Ballets Russes” demonstrates above all a stylistic variety across different media. In contrast to the Russian-modernist orientation of Gontcharova, Alexandra Exter’s backdrops seem otherworldly. Exter, who would collaborate with choreographer Bronislava Nijinska after she left the Ballets Russes to found her own company (Théâtre Choréographique Nijinska) in 1925, showed an aesthetic sensibility that seems to have more in common with the movements in the post-Revolution Soviet Union. Exter’s abstract set designs are among the most striking of those in the exhibit. The obliquely angled rectangles that make up her set design for Bronislava Nijinska’s ballet Holy Etudes stand out all the more against the midnight blue background. Exter’s preference for these abstract designs of rectangles and circles draws a certain strength from her mastery of color. Exter, like Nijinska, may have been more sympathetic to the aesthetics of the new Soviet Union, but those aesthetics do not stop her from sharing Diaghilev’s original vision of ballet as Wagnerian opera in motion.

Alexandra Exter, scene designs for the “Holy Etudes,” 1925, gouache and metallic paint on paper, 17 ¼ x 25 inches

“The Women Artist of Les Ballets Russes” gives due attention to the unique styles and contributions of visual artists Natalia Gontcharova and Alexandra Exter as well as costumiers like Barbara Karinska. However, these artists’ contributions seem to return to the work of choreographer Bronislava Nijinska. Nijinska was not only the artistic collaborator of these female visual artists, but she too was a professional colleague, a one-time ballerina in Les Ballets Russes who trained, wore the costumes, and formed a living part of the vast designs of everyone behind stage. Nijinska’s background as an artist raises fascinating questions: how did her perspective as a female dancer influence her as the first female choreographer of Les Ballets Russes? How did her experience influence how she worked with the women of Les Ballets Russes who worked both on and off stage? The McNay allows these questions to linger in the display case which contained Nijinska’s choreography notebook for the London production of The Sleeping Princess. Nijinksa’s neat Cyrillic handwriting is left untranslated, and so too, are the manifold gender and organizational social dynamics within Les Ballets Russes that influenced the world in which Nijinska made her art. Understandably, the exhibit does not delve into the personal drama that accompanied her relationship with her famous older brother and the siblings’ complicated relations with the sometimes inspiring and conniving Sergei Diaghilev who gave them a stage on which to dance, choreograph, and create. “Female Artists of Les Ballets Russes” makes it more than clear as to the scale of Nijinska and her colleagues’ achievements. As to the obstacles which Nijinska, Gontcharova, and Exter faced in such a storied company, “Female Artists of Les Ballets Russes,” prompts lingering questions.

When it comes to the history of ballet and the role of women artists in one of ballet’s most influential troops, “Female Artists of Les Ballets Russes: Designing the Legacy” more than succeeds. The McNay’s show is a feast for eyes and ears (its spectacular Spotify playlist is available online). The women artists featured in the exhibit testify to the revolutionary potential of Les Ballets Russes during its two decades in existence. And for San Antonians, “Female Artists of Les Ballets Russes,” is an overdue comeuppance. Les Ballets Russes toured Texas only once, performing in Houston, Austin, and Fort Worth in December 1916 before enthused crowds—passing San Antonio by altogether. Bronislava Nijinska, however, stayed behind in war-torn Europe. Now, 108 years later, Les Ballets Russes shows the Texas city it passed over, the contributions of female artists who have been long too neglected.

Female Artists of Les Ballets Russes: Designing the Legacy is on view at the McNay Museum of Art through January 12, 2025

Entrance included with General Admission (Free General Admission Thursdays 4-9 pm

Recent Comments