The legacy of our fathers, Father. Our mothers, Mother.

In Soy de Tejas, curator Rigoberto Luna brings together a contemporary re-examination of the Tejano/a regional family tree. This exhibition asks about the origins of Texas (or Tejas), examining the Spanish-Indigenous Americas and the revolving, evolving growth from the bloodshed of colonization and its aftermath, a local reality exemplified by Mission San Antonio de Valero, commonly known as the Alamo.

Centro de Artes’ gallery is located in downtown San Antonio, on Produce Row. Enter the deep blue and magenta-colored building and you find a haven for those seeking corresponding stories, structures, and reasons for the walking experience across the heart of San Antonio (or, Anthony of Padua), the Franciscan patron saint of castaways and lost things. The building’s vast galleries, spread out over two floors, feature 40 artists working in varying media.

Installation view of “Soy de Tejas,” courtesy of the City of San Antonio Department of Arts & Culture.

The show strikes a good balance between intimacy, connectedness, and flow. It is curated into open passageways that connect wall spaces and intimate corners of approximately one to three works per artist, which draws contemplation on their respective approaches. Both floors have a single large wall partition in the middle that designates a bilateral directionality from one end of the gallery to the other, with stairwells on either side. As a result, from the center of each floor, you can get a panoramic view of many of the groupings of artworks, or if hidden around a corner, you can hear them.

The lighting is slightly low throughout, and while it might lack contrast and guidance, this has an effect of inviting a slower and more willful experience on the part of the viewers. The exhibition is not arranged into themes, and there are no wall texts to guide the viewer from one section to another; the show is instead designed for the viewer to wander and explore the works, as well as the memories and feelings they elicit. The wide variety of artworks throughout the show are categorized by media in this review, to examine a sense of the patterns that emerge from this survey of Latinx artists from Texas.

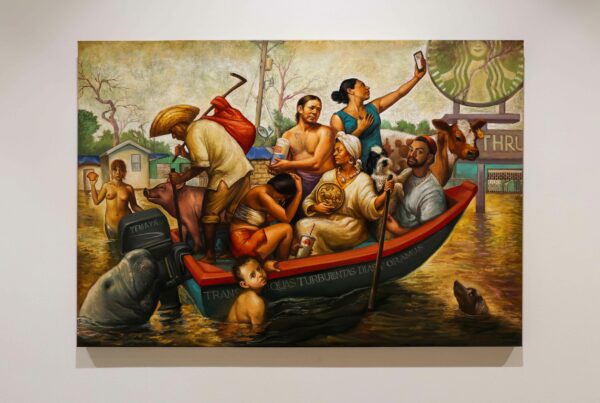

Patrick McGrath Muñiz, “Diasporamus,” 2021. Photo: Essentials Creative. Copyright Patrick McGrath Muñiz.

Paintings

Kingdom come-turned-horror, with the floods of hurricane seasons along the Gulf, where roads have become waterways is shown in Patrick McGrath Muñiz’s Diasporamus (2021). Muñiz paints in the rounded figurations of Diego Rivera, following the Mesoamerican tradition, but softer. He depicts folks and a menagerie of animals on a tin boat, and the composition is speckled with repurposed seafaring corporate symbols from Shell to Starbucks. Like Muñiz’s work, paintings take up a prominent place in the show among a forest of other media.

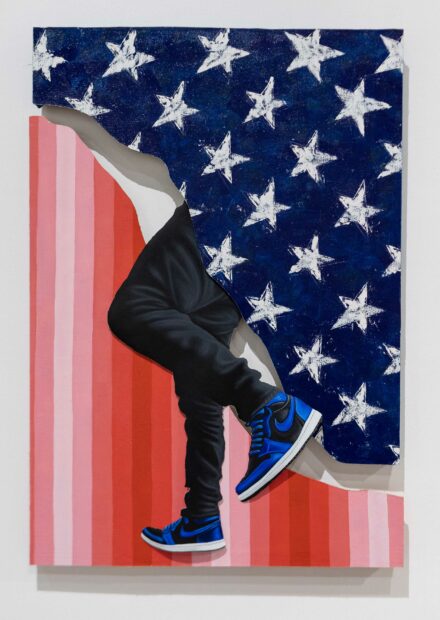

Alejandro Macias’s pop-Americana Ascension (2022) is a mashup of classic Nike Air Jordans and Mexican serape, and Arely Morales’s portrait Mi Apá (2018) captures the casual grandeur of an outing, her figure wearing a backwards cap and holding a portable Igloo icebox. Joe Peña paints the still otherworldliness of fast-food nightscapes of South Texas, and in the diptych Pasadena 1 & 2 (2023), Jasmine Zelaya’s mute, brown women in verge of flat abstraction are brought back to life by reforming teardrops into florets. Francisco Moreno’s Mother and Child (2020-21) is Northern Renaissance-meets-contemporary-suburban-pastiche, with the pair altogether blissfully engulfed in celestial flames.

The negotiation between environment and faith is the subject matter of Marianna T. Olague’s Virgen por el Gateway South (2021). A yard shrine of La Virgen de Guadalupe encased in bars and Christmas lights stands against the backdrop of a yellow brick house, with flickers of dry weeds across a red brick and concrete-tiled yard — these various inert objects are interrupted by a fresh bushel of cut flowers.

Less earthly and more surreal is the work of Jaylen Pigford, negotiating Blackness Mexicanness in El Negrito (2022), which depicts black crayons and lotería, watermelon and lime, and Mexican shaved ice and hair pick. Enchilada Plate To-Go (2020) by Eva Marengo Sanchez is a sumptuous chiaroscuro still life of enchiladas in Styrofoam containers sitting in a white plastic bag. Mirroring our experiences, this daily bread sits next to a container of sopa and salsa roja and verde in plastic 1 oz cups, and tortillas still wrapped in foil, all on top of a vermillion tablecloth patterned with blossoming fruits and roses.

Eva Marengo Sanchez, “Enchilada Plate To-Go,” 2020. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright Eva Marengo Sanchez.

Video, Mixed Media, and Installation

Funny thing happens when “eating” is made inert in video. Foods are turned tableaus in documentary collages of vegetables shot on low-res video in Dinner as I remember (2016) by Francis Almendárez. Videos are omnipotent presences throughout the show, filling the halls with disparate intersecting sounds about identity in rhythm and cadence. “Wash us of our sins,” implies Natalia Rocafuerte’s Pocha Dreams (2022), with running streams of bright 90s stationary kitsch projecting rotting fruits describing “pocha,” a derogatory term for Mexican Americans who speak in a mix of English and Spanish, often called Spanglish. The work is obliterating, negating its self-infliction of pain, for both those lost and condemning.

A journey of reconciliation is one that Vick Quezada performs in their See Unseed (2020), a walking journey between three Spanish missions in El Paso, and through the city’s breadth of natural and arid suburban landscapes which is shot in saturated color. In this spiritual walk, they reflect on the confluence of the Aztec worldview with science, from the Precambrian world to the present. On the other side of the galleries, this reconciliation is recognized in the personal and familial, in differences between siblings, in Sisters (2023) by Ingrid Leyva. Her video is a construction of two-channel sisterhood through two-second clips of found footage, Google searches, and first-person journeys on camera phones.

Mixed media works unpack the concepts of survival, sin, and forgiveness in the material realities of Tejas. Forgiveness does not come easily; in the work of Josué Ramírez, an aggressive signaling of red and yellow cardboard people and homes are constructed from predatory “We Buy Houses” signs found in low income neighborhoods.

There’s also pride and ownership in the logic of castaways in Cande Aguilar’s Mannerist hodge podge of graffiti on wood panels, or Gil Rocha’s assemblages of found objects, with cobbled fences, wires, yard signs, lamps, shoes, and plastic bags, altogether standing in defiant irony. Raul de Lara’s broad shovel refuses work in another ironic twist, with its wooden handle curled into a knot in Cansado (Tired Tool Series) (2022).

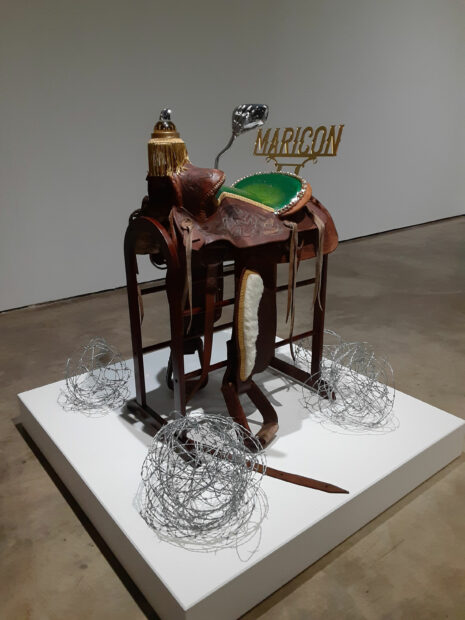

A strategy against the sin of self-hate, again, is to take ownership of the pain and then reclaim it. José Villalobos’s QueerRider: Maricon (2022) is a gaudy saddle with the derogatory gay slur “maricon” written proudly across the rear. Ruben Luna offers a balm to the community in El Baile de Rico y Lola (2023), where love is expressed by a pair of Tejano/a dancers (in honor of his parents) with crayons clasped onto the heels of their shoes as they sketch a series of starlike marks on the floor.

Deliver us from evil. Violette Bule’s strength testing bell installation is a chance to Slam the Dreamers (2015-19), with DACA rewards at every level (more deportations = more money for private penitentiaries). Making the costs of the showing of brute strength visible is Juegos Fronteras: Merry Go Round Port of Entry (2013) by Angel Cabrales, in which playground equipment is made inaccessible by the violence of fences and surveillance equipment. Stephanie Concepcion Ramirez’s cocoon of tarp protects from social violations in vibraciones de temblores (2022), visibly obscuring an oblique tale about wayward sons, daughters, and mothers inside from peering eyes.

Photography, Ceramics, and Drawings

Now, back home and back to family, in photographs. Tina Medina and Melissa Gamez-Herrera investigate memories and realities through the intimacies of family and domestic portraits. In Medina’s They Didn’t Know We Were Seeds (2022), archival photographs are shredded and then rethreaded into U.S. and Mexican flags, expressing the hybridity of the Latinx diaspora. In Gamez-Herrera’s photographs taken between the border towns of Acuña and Piedras Negras, Mexico, individuals are seated inside their homes, awash in both artificial and natural light. These photos show the U.S.-Mexico border from the perspectives of people living along the geographical divide. Their lives are ordinary – far from the violence as depicted in mass media..

Karla Michell García, “La Línea Imaginaria,” 2022. Courtesy of the City of San Antonio Department of Arts & Culture. Copyright Karla Michell García.

Solace and containment appear in hard and fragile ceramic forms, like Karla Michell García’s La Línea Imaginaria (2022), a series of bloated, blubbering, bulbous vessels of desert cacti in raw clay. Gabo Martinez’s swaying red droplets on glazed terracotta plates with an all-seeing eye in Ojos de Sangre (2023) reinterpret Mesoamerican symbols of power and energy. Across the gallery, the viewer can navigate back from symbolism to reality through drawings by Fernando Andrade, whose transitional dream-like graphite figures are swimming in acrylic in Isolation (2021) and Numb (2021).

Drawing takes a more physical form in Christopher Nájera Estrada’s a dios le pido (2020), where a melting pair of hands in shimmery graphite are hanging in prayer upon a rosary. Ashley Elaine Thomas uses graphite to flatten, collapsing a long perspective out the Window View on John Street (2020): a moth spreads its wings toward the full moon, surrounded by dreamy Gulf Coast oil refinery pipes dotted with incandescent lights, next to the soft circle of light around a nightstand lamp.

Prints and Fiber

The remaking of Tejas, with prints and in fiber. Sara Cardona breaks architecture in her assemblage of printed structural imagery, accented with neon paper binder rings and post-its. Disrupting architecture takes a three-dimensional form in a nonsensical, non-functional, 12-feet-square architectural column by Sarah Zapata. The piece, Towards an omnious time II (2022) has colorful tufts of felt mapped out across it in repeating patterns and shaggy patches.

Imagery from roadside subculture, recalling long drives along Texas highways, makes an appearance in Juan de Dios Mora’s print ¡Ya Basta Con La Rabia! (2020), where a bullet is shot from a wolf’s maw, which is drawn open with chain links, bristling with semi-automatic bullet teeth. Bella Maria Varela remakes landscape with her sublime bald eagle Tu Hija (2018), where we find a Frederic Edwin Church-like scene across a fleece cobija. The blanket is cut and draped with pink neon sequined fabric and matching fishnet stockings filled with found objects, as a kitsch derealization of manifest destiny.

In the show, sincerity is not lost among the irony. Marco Sánchez’s relief prints of frenetic, stormy shorescapes with figures overlooking still to high waters in Gentilezas y Rudezas (2020) bring us back to feeling both the gifts and punishments of nature, reflecting the wide experiences of life itself.

Chris Marin grounds this range of emotions in real objects with Falling Out the Sky (2021) where fabric and polyester fillings could be found stitching together desperation, with rows of pillows confessing, “It’s hard to live in the moment unless life’s hard.” This journey is expressed through a turn to abstraction in Gabriel Martinez’s untitled (2019), where quilt-scaped canvases of found fabric join surreal patterns that resemble the ups and downs of life along the Gulf.

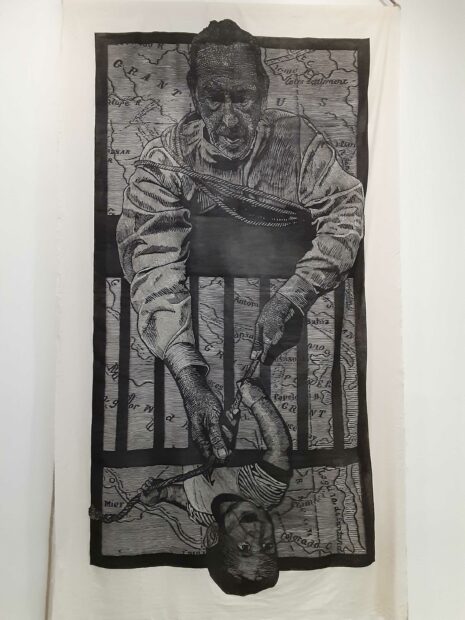

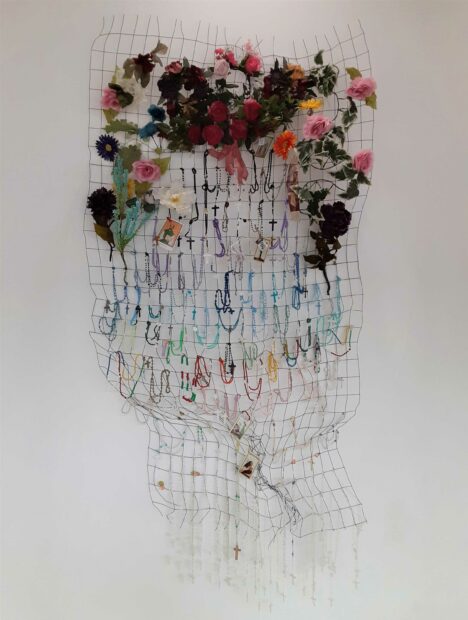

Perhaps in the cuts of prints and the knots of fiber, more than in other media, one finds a reconnection to our fathers and our mothers. Across the two floors, Omar González’s Fatherly Dilemma (2020) and Benjamin Muñoz’s Eternal Endeavor series (2018) show generations pushing and tugging their marks across historical and symbolic maps of Tejas. Old and worn family clothing, neatly folded into two piles underneath a pair of clear plastic platform heels in Laundry High Heels (Relic) 1 & 2 (2021) by Christian Cruz reminds us of the extreme gap between the overt sexualization and the domestic maternalization of women. Finally, Jenelle Esparza weaves family histories in Holder/Receiver 1-3 (2022-23), where each fiber, each micro turn of thread, each cloth flower, and each rosary bead captures a memory and a feeling of place.

Soy de Tejas

This survey should be a call to Texas art institutions about the representation of our culture and history. Up until this point, the pulse of art in Texas has been gauged by Big Medium’s Texas Biennial, and specifically in regards to Latinx art, the Mexic-Arte Museum’s annual Emerging Latinx Artists (ELA) exhibition.

According to estimates released in 2022 by the US Census Bureau, 40.2% of Texans identify as Hispanic. Tejano/a art is not Mexican, is more geographically specific than Mexican American, and is very much a core part of Texas history, demographics and culture. Yet, it is marginalized as “ethnic,” and in the wider Texan context, as a hybrid curiosity. What is the value of art institutions that don’t reflect back the history of a majority of the people they are meant to serve and educate?

We could find ourselves instead in the jowls of downtown, in the arms of Saint Anthony, a short ways from a mission renamed the Alamo. Soy de Tejas tells us the story of Texas as we feel it, through Tejas, in our daily sights and encounters. This art is not tradition, not Chicanx, but rather the new mundane, hybrid reality between the Indigenous and the diasporic, one that is specific to Texas.

Soy de Texas is curated by Rigoberto Luna. It is on view at Centro de Artes in San Antonio through July 2, 2023.

Recent Comments