Based in Bastrop, the painter Ellen Tanner painstakingly creates microscopic worlds that beg viewers to draw near. Her works, though smaller in scale, are inspired by the hallmark detailing of Flemish masters. Over the years, she has tackled a diverse range of complex subjects including Aesop’s Fables, Greek mythology, and the animal kingdom.

Tanner, who holds a BFA in Graphic Design from the University of North Texas, began her artistic career as an illustrator and graphic designer for Fossil. After several years in the role, she returned to college, receiving a BFA in Art Education from the University of Texas in 2005.

In 2017, the Art Museum of Southeast Texas organized a solo exhibition of her work which traveled to the Galveston Arts Center in 2018. The exhibition was accompanied by an illustrated catalog featuring texts from the artist, exhibition curator Sarah Beth Wilson, and Lamar University professor Dr. Maria Elena Sandovici.

Tanner and I recently discussed her artistic practice along with several of her bodies of works.

Caleb Bell (CB): You create pieces on the smaller, more intimate size. To me, I see that as a way to intentionally draw viewers into the world you have created. Would you agree? Can you elaborate on the role size and scale play within your work?

Ellen Tanner (ET): Yes, absolutely. It is true, I think that one can’t really see the full range of details I pour into each of these without looking through some sort of magnification. I look through two layers while working – strong readers and an Optivisor headband magnifier over those. I suppose I enjoy the idea that, if someone does take the time to come close and look through magnification, they will see something quite a bit more nuanced than is visible at a distance or to the naked eye. I love that intimacy of inviting someone close to these small worlds I have spent hundreds of hours on, even though I’m left out of that exchange when they leave my studio.

Typically in my work, I have been scaling all the elements down significantly from actual size, which can be frustrating when there is something I would love to spend time rendering but cannot due to scale. When I was anticipating painting Cerberus, I had him originally planned for a four-by-six-inch scale, but I couldn’t bear the thought of not having the chance to pay homage to a Bullmastiff’s fabulous lip ruffles due to that tiny canvas. For that painting, I chose to scale up quite a bit from my usual size so that I could really sink into the details and color shifts. Currently, I am heeding the siren song of the insect kingdom and spending some time exploring the mind blowing pattern and color lavished across their tiny forms. What’s neat about doing the insects is that even though the paintings are still very small, the insects themselves are scaled up from actual size, which is quite the opposite of what I am used to doing.

Ellen Tanner, “Aristaeus, Keeper of Bees,” 2016, oil on panel, 6” x 14”. Image courtesy of Moody Gallery, Houston

CB: I’m glad you brought up your series on insects. I want to discuss a few bodies of your work, so let’s start with your current exploration. What was your initial draw to insects as subjects, and what was the first painting in the series?

ET: The first insects were the bees of Aristaeus many years ago. When I painted the myth of Aristaeus, it was such a tiny painting that the scale of the bees swarming from the slain animal was smaller than a grain of rice. That was very frustrating. As I studied pictures of bees, I saw all the textures and colors I hadn’t realized were there, having only ever looked at them in real life with the naked eye. Due to this realization, I treated myself to a separate study of a bee scaled up so I could explore all that on a larger scale. When you zoom in on almost any insect, an unexpected treat awaits — shimmering, gossamer, furry, bumpy, unusual pops of color, deep rich mattes, and flawlessly airbrushed gloss – sometimes all in the same insect! So back in 2016 when that seed was planted, there was this really astonishing new world of visual delight to explore — the population of which is increasingly decimated by the shortsighted actions of our species. If only we had taken the time to understand and appreciate insects more, maybe we wouldn’t be in such a terrible pickle now.

This series is all about studying, celebrating, and exploring these amazing creatures and their behaviors. And since they’re stuck with us, I may delve into the cross-section of human and insect, and how we have made sense of them through the ages vis-a-vis folklore. I have a rather large, for me, and terrifyingly white, gessoed board lying in wait in my studio for which I am playing around with this idea. One insect I will definitely be steering clear of is the magnificent jewel wasp, whose ghastly behavior of zombifying cockroaches is the stuff nightmares are made of. A terrible beauty nonetheless!

Ellen Tanner, “Bee Study (Aristaeus, Keeper of the Bees),” 2020, oil on panel, Tramp art frame, 5 3/4” x 7 3/4” (framed). Image courtesy of Moody Gallery, Houston

CB: I remember that painting of Aristaeus from your solo exhibition Fables, Families & Myths at the Art Museum of Southeast Texas. It is from your series based on Greek mythology, which you explored for many years. Why was it important to you to visually retell the Greek myths?

ET: Fulfilling a childhood dream, I suppose, that was still hanging around in my adult years when I found myself in a fortunate enough position to make it happen. I am sure I could have spent far more than the five years I did spend on the series exploring the myths and their complex interconnectedness, and still not feel satisfied that I had even scratched the surface. While I never imagined I would find myself gripped in the maw of a sea monster or transformed overnight into a bear, I am ever aware that some odd twist of fate could touch down at any moment and turn my life or the lives of those I love upside down, as is the case in so many of those ancient tales.

Aside from the absence of scientific knowledge, I think the myths have remained very relevant to humans engaged in the daily beat of life on this planet. Still, we find ourselves caught somewhere along that very human continuum of experiencing the tenderest humanity and the basest brutality. We are at the mercy of the power of the natural world which sustains our very fragile breath. Still beating on our doors are those age-old themes of vanity, lust, greed, and hubris, invited in by some and kept at bay by others. These stories always have the capacity to teach us a thing or two about humility, but the more things change, the more they seem to stay the same with regard to that.

CB: Would you say those are the same reasons you previously worked with Aesop’s Fables?

ET: Yes, I guess I am attracted to narratives that cut away a crisp window into the human experience and echo across an expanse of time. I find the fables to be deliciously clever in their simplicity, and they really do cut us down to size.

CB: The first work of yours I can vividly remember seeing was from your Love and Loss Families series, which was between the fables and the myths. For the piece, you had created a whole familial narrative around anthropomorphized sheep. In addition to individual painted portraits, you created and collected “heirlooms” that were all housed in an accompanying wooden box. Can you share where that series concept came from?

ET: Oh yes, that series was very dear to my heart. As a child I always loved books of fables and artists such as Beatrix Potter, so my imaginative play usually involved anthropomorphized animals. This series was a continuation on that theme. I had also gotten really interested in different mourning traditions, especially those in the 1800s which are rather macabre for modern tastes, but I actually found them to be so lovely. They seemed to have a more nuanced way of viewing life and processing mortality. It wasn’t just moments of happiness and joy memorialized, so a more well rounded picture of what it is to be human seems to emerge from some of their customs and keepsakes. Although they rarely sat for pictures due to expense, portraits of family members in mourning were a custom during that time, sometimes even posing with their deceased loved ones. There were mourning ribbons and extravagant works of art made from the hair of loved ones. There were also deeply moving mourning embroideries which were another custom of the time — the repetition of the hand movements thought to be a good way of moving through initial stages of grief while honoring the deceased. And then, reaching further back in history, the hand painted skulls in Europe are exquisitely beautiful. So, while studying these traditions of memento mori, I had the idea to make this series.

Ellen Tanner, “Hughes Family,” 2014, mixed media, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of Moody Gallery, Houston

I have long been fascinated by the physical fragments of a life that survive from one generation to the next until they become so far removed that these ancestors lose their context in our family histories and end up anonymous in a box or antique store somewhere. Since I spend a lot of time poking around antique stores, I see the many broken threads we fellow humans uncover years later. Sometimes it is enough to provide a patchwork story of a once vibrant life, and sometimes it’s just a single lonesome image, untethered from all intimate connections that bound them in life. The question of what physical reminders of our lives will outlast us and for how long is deeply fascinating for me.

CB: I know a lot of your frames come from antique stores. You often use vintage union cases and Tramp art frames for your paintings. What role does framing play in your process? How did you land specifically on these two types?

I enjoy old objects and old spaces — really anything with a sense of time having passed that seems to lend the object or space a certain soulful quality. I also like the idea of an unexpected partnership or connection with a craftsperson or toiler who had hands on the object maybe hundreds of years ago. And then there’s the journey the frame had before it ended up in my path and all the hands it passed through to get there — I find pleasure wondering about that too.

I am very enamored with Tramp art due to its history and the warm, earthy quality of the frames created within that tradition. I think the pairing of these obsessively wrought, quirky frames with my obsessively worked paintings is a good partnership, even though the first is more folk art and the other more academic or skill-based art. I like the balance struck between the two and think they each lend a little something to each other. The Tramp art frames can be a bit dictatorial with regard to what will work inside them. I really have to build the color up while it’s sitting inside the frame and make sure some tones are exchanged between frame and painting, or it won’t feel settled inside it. And sometimes the antique frames also demand a certain subject, like the two old WWI frames I came across this summer. One was an old metal Americana frame that definitely had to have a bald eagle in it. And the other was a super quirky Canadian 1915 WWI era frame that somehow is ending up with a homing pigeon outfitted with a message and an antique camera. I did not realize homing pigeons were used widely during WWI to send messages and were occasionally used during this era to snap aerial photographs as a kind of precursor to a drone, I’m not sure how exactly that idea rose to the top as the correct one for the frame, but something always does after much wondering and agitating. So those two frames required a brief departure from the current series.

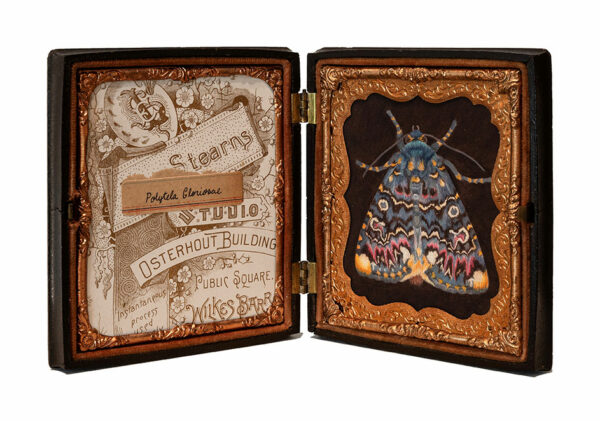

Ellen Tanner, “Polytela Gloriosae,” 2024, oil on panel, Thermoplastic union case, 3 3/4″ x 6 1/2″ (case open). Image courtesy of Moody Gallery, Houston

As for the union cases, I am attracted to the intimacy of those, their scale, and the moment of opening the heavy black case to reveal something finely wrought and colorful. But most especially, I love the very rich patina of the antique golden mats, which can vary from green to gold to coppery. Again with those, the tones must be exchanged between painting and mat, or they will feel off inside the case.

The union cases are still fairly widely available and can be found for affordable prices, but the Tramp art supply out there seems to be dwindling and they get ever more expensive. I am thinking with the new series concerning the intersection of insect and folklore, I will emancipate myself from the tyranny of the frame (ha!). Betty Moody helped to design some very lovely ones in my early days there at Moody Gallery, and I know if anyone can help find a good solution, it’s her. But I will always be on the lookout for fabulous antique frames for the smaller works.

CB: A few years ago, you combined a lot of these longstanding ideas together to create the editioned portfolios Fauna, Volume I and Fauna, Volume II. Those suites include prints of your paintings in ornate mats housed in clothbound boxes. Were they your first foray into editioned pieces and are there plans for possible others?

ET: Yes, that was my first attempt at such a project and I would dearly love to do another someday. There were a lot of moving parts to those and many people I am extremely indebted to for helping me get that project completed: Betty Moody and the whole Moody Gallery team, of course, always my guiding stars; Melissa Miller and Bill Kennedy, for the beautiful scans and color corrections as part of their Happy Trails Editions project; and the fabulous Jace Graf at Cloverleaf in Austin, who made the lovely boxes and helped guide me through the letterpress and foil stamp design process.

Those were labor-intensive to the extreme as I made and hand-decorated all the mats, plus I had to dust off my graphic design skills for the other components. But it was thoroughly enjoyable, and it reminded me of why I was attracted to graphic design during college.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Recent Comments