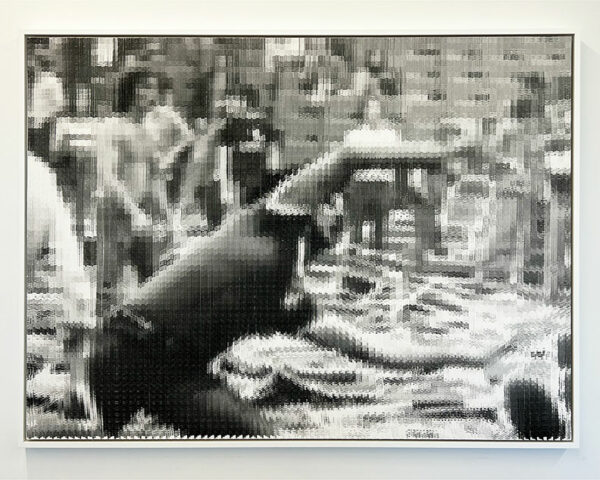

John Sparagana, “Projectile #24,” 2017, multiple archival inket prints sliced and mounted on dibond aluminum, 36 x 49 inches

The crowd and the photograph. The two frequently collide, and the artist John Sparagana has often used photographs of crowds as the raw material for his sliced and mixed work. This is indeed the case in his current exhibition, “Projectile,” at Basket Books & Art where the artist recomposes a news photograph of a raucous crowd throwing chairs after a 1980s rock concert ended early. One of these constructed images, Projectile #24, shows the torso of a person horizontally stretched across the image as they have just let go of a chair, which, cropped from view in this iteration, flies through the air. Behind the figure, one sees a pile of collapsed folding chairs and people milling about. There is an oddity here in the way the dynamic pitch of the front figure is opposed by the static bodies and objects in the background, and this signals one of the primary elements in Sparagana’s works — the artist generates tension in the apparent gap between the dynamism of a moment as it is transformed into the stasis of the still photograph. Indeed, throughout the artist’s series of Projectiles, one apprehends that the there-and-then of a photograph intermingles with the here-and-now of the present.

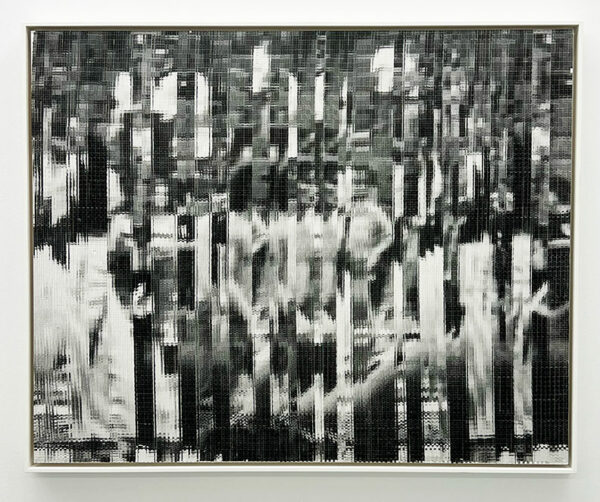

John Sparagana, “Projectile #25,” 2017, multiple archival inkjet prints sliced and mixed on paper, mounted on dibond aluminum, 48 x 42 inches

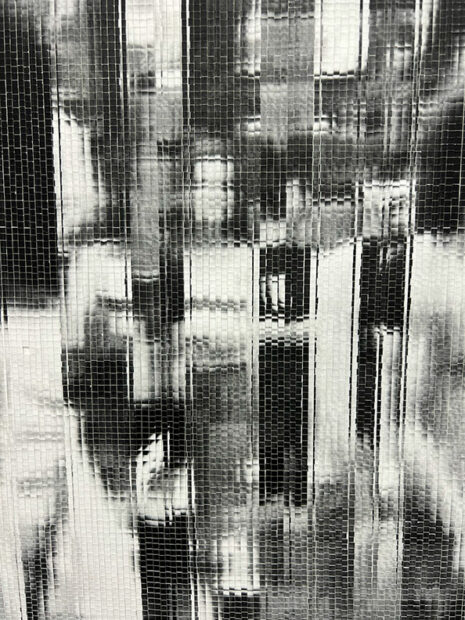

However, temporality might not be the first thing one notices when looking at Sparagana’s works; most prominent is the deeply material presence of the cut-and-pasted objects. Looking at Projectile #25, a distinctly cropped section of the same news image, one notices the physical surface of the artist’s collage. Several small squares of the image have flaked off, especially in the upper-right corner, and the left edge is jaggedly chipped away. These and other details insist viewers consider the image as a material thing as much as it evidences the hand-made process Sparagana takes to produce these works. Beginning with mass-produced images, the artist remakes them as archival prints and then cuts them up. In the first stage of cutting, Sparagana slices the image vertically into roughly 1/8-inch strips and then sequentially reassembles them. Then he cuts them horizontally at the same width and reassembles them again. The final image is a gridded composite of multiples of the original, which is partially blurred and vibrates as a result of the image’s newly distorted spatiality: it is enlarged and recomposed into an uncanny grid.

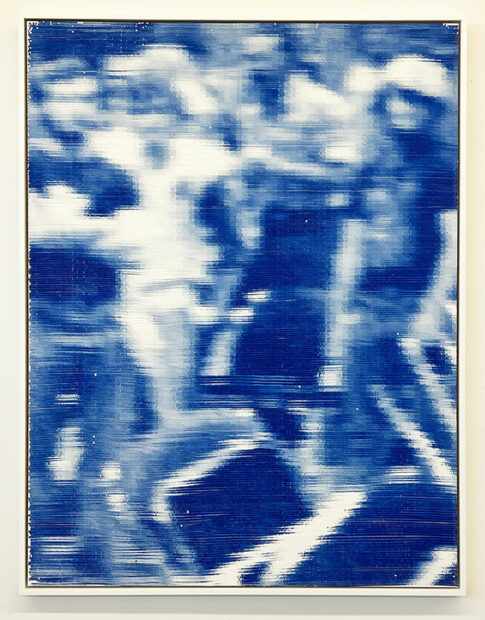

John Sparagana, “Projectile #14,” 2017, multiple archival inkjet prints sliced and mixed on paper mounted on dibond aluminum, 24 x 39 inches

In this sliced and mixed work, the physical manipulation of the image also generates a new temporality: transmogrified from news images to fine art, the photographs incite new attention, and more than that the blurred vibrating visual effects shift the speed with which one consumes photographs. Sparagana started making this style of work in 2007, and in doing so he appropriated images from mass-media magazines like Time and Newsweek. These and other glossy magazines were first published beginning in the early 1920s, and at that time the magazines themselves had instigated a type of serial viewing where one was incited to continuously flip from one page to the next to view one photograph after another (a process now accelerated in social media scrolling). Sparagana pushes against this fast serial consumption: he not only produces multiple iterations of the same image, uniquely cropped and colored, but also distorts the source photograph in such a way that demands one to slow down to decipher the image. Some are relatively easy to interpret, while others are less so. Projectile #23, for instance, shows a figure (or two?) in a murky field of blue; other details are hard to make out. In Projectile #14, one is called not so much to pick through the image content than to study the vertical elements formed simultaneously by the source image and Sparagana’s cuts. On the bottom left of this work, there are two vertical white lines within a field of black. These white lines mimic the vertical cut lines made by Sparagana, but in fact, they are part of the initial photographic image — perhaps the edge of a chair’s light-colored metal frame as it abuts its dark cushion. The enlarged image and its handmade details, then, encourage slow looking — an affront to the serial consumables of glossy magazines and social media posts alike.

John Sparagana, “Projectile #14” (detail), 2017, multiple archival inkjet prints sliced and mixed on paper mounted on dibond aluminum, 24 x 39 inches

What does this type of repetitious image consumption have to do with the music-going crowd that Sparagana uses as the subject of “Projectile?” The specific source image derives from a 1983 Neil Young concert in Louisville, KY. A decade or two into its commercialization, the music industry — not dissimilar from mass-produced magazines — had largely embraced serial consumption models, and popular music (already by the 1980s) existed within a relatively narrow range of variation. Despite this, Young started his set not with the familiar rhythms of “Heart of Gold” and “Like a Hurricane” but rather with about an hour of disco-inflected electronica. Suffering from a flu that worsened throughout the night, the musician ended the show early, before getting to his most popular songs. Dissatisfied with the experimental digression, the crowd erupted. Young’s electronica forced his audience to listen closely and to think anew about music; they were not permitted to fall into that unchallenging listening experience of hearing what they know (and knowing what they like).

But the linkages between crowds wanting the hits and serial image consumption goes further than a general critique of media, in Projectile Sparagana points to a broader crowd mentality that curtails critical thinking. This is perhaps to paint with too wide a brush, but as the so-called democratization of communication collapses into mob/mass distortion of facts, as entertainment careens into the unchallenging mosh of the easy, and crowds, when they do form, do not challenge the status quo but rather insist things be put back the way they were, Sparagana’s work dwells on the trajectory of projectiles thrown in the 1980s that continue to land in the present. The materially deft, deceptively beautiful, sliced and cut Projectiles, ask one to look closely and actively, to think historically about the mesh of “easy” entertainment, and ultimately to get beyond the crowd. What could be more prescient today in November 2024?

Further reading: Reto Geiser, David Grubbs, John Sparagana, Projectile (Chicago: Drag City Books, 2021).

Projectile is on view at Basket Books & Art through December 7.

Recent Comments