Author’s Note: This is the third in a series of articles from a recent trip to New York. Click these links to read about La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela’s “Dream House” and El Museo del Barrio’s “La Trienal 2024.”

I have a love/hate relationship with museums. Many of the most renowned art museums in the U.S. are predominantly white institutions, a phrase which originated as a descriptor of higher education institutions in which 50% or more of its student body identifies as white. The term is used to describe cultural institutions that embody white-dominant culture and center whiteness. In museums, this manifests in various ways, including the inequity in staffing positions, the demographics of collections, and the lens through which art is presented. As such, a specific aspect of museum culture that also holds mixed feelings for me is period rooms.

A period room is a classic museum creation, a curated space that brings together decorative arts, such as furniture, textiles, and functional items, with period-specific artworks. I like to think of these rooms as the first immersive art spaces, because where museums typically showcase items out of their original context, period rooms are an opportunity to add a layer of history and narrative to an otherwise lifeless object. Most period rooms are fabrications, though some like the Dallas Museum of Art’s Wendy and Emery Reves Collection (which until sustaining rain damage in 2022 was a 16,500-square-foot space with galleries that were reproductions of rooms from the Reves’ home in Southern France) are designed to mimic a particular place.

Generally, when I think of period rooms the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston’s American rooms and the Art Institute of Chicago’s miniature rooms come to mind. So, I was excited to hear about Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art during a recent visit to New York. Massive museums like the Met are nearly impossible to take in all at once, so when I visit these spaces I make a plan to see one or two things — quality of experience over quantity.

Before Yesterday We Could Fly is a one-room installation, a surreal space found among galleries dedicated to Medieval Treasury and Italian Sculpture and Decorative Arts. In a video on the Met’s YouTube channel, Sarah Lawrence, the Met’s Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Curator in Charge of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts (ESDA), explained the origins of the exhibition stating that when Max Hollein, the Marina Kellen French Director and Chief Executive Officer came to the museum in 2018 he challenged the curatorial team to consider what a contemporary, or even futuristic, period room might look like.

Lawrence and Ian Alteveer, the museum’s former Aaron I. Fleischman Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, were mindful of not recreating a Eurocentric, classist depiction of a time and place. They wanted this potential space to have a connection to local history and to center on narratives that have been missing from the museum’s collection, in particular, they focused on the history of Seneca Village, a 19th-century predominately African American community that was displaced to construct Central Park. Specifically, they considered creating a period room through the lens of Afrofuturism to imagine what a Seneca Village resident’s descendant’s home might look like had the community not been decimated and instead generations had thrived in the space. The curators noted that as they are both white, the story was “no longer [theirs] to tell.” Instead, they brought in Hannah Beachler, the production designer for the movie Black Panther (which visually embodied Afrofuturist ideas in the creation of Wakanda), and Michelle Commander, Curator and Associate Director of the Lapidus Center at the Schomburg Center for Research of Black Culture at New York Public Library.

The space that Beachler and Commander designed and curated is magical; it at once speaks to the past while manifesting a fantastical future. A wooden house structure takes up much of the space within the gallery and visitors are able to walk along its perimeter. The home has an array of cutaways to reveal the interior space, which is filled with a blend of historic and contemporary pieces. Objects like a wooden butter churn, an iron kettle, stoneware jars, and Venetian glass, are at home among artworks by Elizabeth Catlett, William Henry Johnson, Roberto Lugo, Willie Cole, Fabiola Jean-Louis, Tourmaline, and others.

The house features a living room and kitchen area, communal spaces where people gather and share. Beachler has noted the importance of these spaces to the keeping of histories. She explained, “Oral tradition is the only thing the Black community really had to move their stories and traditions forward.” A hearth is at the center of the space and Beachler speaks both about the gathering around a fire to tell stories and that she imagined it as a time machine, bringing things from the past and future together in one space.

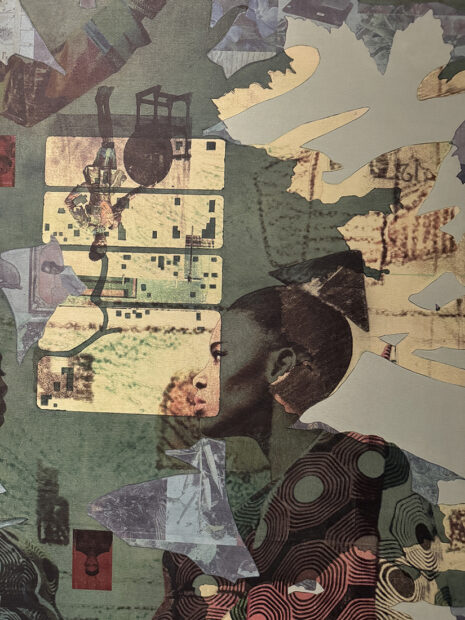

Detailed labels can be found on the exterior walls of the house next to the small cutouts that provide windows into the space. The gallery walls that enclose the house are covered with wallpaper designed by Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Titled Thriving and Potential, Displaced (Again and Again and…), the piece layers a range of imagery related to the lived experiences of residents of Seneca Village, such as foliage of an okra plant, a hand-drawn map of the community, and portraits of 19th century Black New Yorkers.

The space is relatively small, again confined to one gallery, but it is packed with objects that are replete with history and meaning. It was overwhelming to be in the space; to consider what was lost, purposefully taken, so that Central Park could exist; to grieve for a future that was interrupted. Of course, the artists’ work and curatorial vision is impressive and bring to mind the idea of resilience. But resilience is a heavy word, while it means the ability to withstand and conjures ideas of strength, it also bears the weight of the reality of the centuries of mistreatment and violence that Black communities have been forced to endure.

Before Yesterday We Could Fly opened three years ago, in November 2021, and is listed as an ongoing exhibition without an end date. I hope that the Met keeps this period room up indefinitely, as it is a powerful and unique space that deserves to be seen alongside the other moments in time on display in the museum.

Recent Comments