Author’s Note: This is the fourth in a series of articles from a recent trip to New York. Click these links to read about La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela’s “Dream House,” El Museo del Barrio’s “La Trienal 2024,” and “Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room” at the Met.

Last year during Chinati Weekend, an annual art event hosted by the Chinati Foundation in the West Texas town of Marfa, I had the opportunity to experience Robert Irwin’s untitled (dawn to dusk) at sunrise. Opened in 2016, the site-specific piece was years in the making and hosts special morning and evening viewings a few days out of the year (though tours are available as part of the organization’s guided tour program). As the morning light streamed into the building and shifted through the space, it conjured personal memories, reflections on the passage of time, and a deluge of emotions — it was therapeutic. Later that day, I attended the screening of Robert Irwin: A Desert of Pure Feeling, a 90-minute documentary about the artist’s career by Jennifer Lane. The film provided context about Irwin’s life and work, deepening my understanding of untitled (dawn to dusk).

Through the movie, I learned more about Irwin’s work on Dia Beacon, a Dia Art Foundation site dedicated to large-scale installations and located in the Hudson River Valley. The artist was invited to create a master plan for the space, transforming a former Nabisco factory into an art destination. Irwin’s careful consideration of light is evident throughout Dia Beacon in the use of scrims in the clerestory windows and the play between opacity and transparency in the window panes of the exterior walls. Walking through the space was like being transported back to Irwin’s piece in Marfa. During my three hours at Dia Beacon, I constantly noted the shifting of light and how it changed my perception of the space and interacted with the artworks.

It is unsurprising that Irwin was involved with both the Chinati Foundation and Dia Beacon; though in separate parts of the U.S., both institutions are situated in smaller towns rather than big cities and committed to large-scale long-term installations. Being a venue for and steward of monumental artworks is an admirable commitment, but it also requires a large amount of space. As such, both sites bear inherent issues related to land, ownership, privilege, and gentrification.

The Dia Art Foundation was established in 1974 by Fariha al-Jerrahi (formerly known as Philippa de Menil), Heiner Friedrich, and Helen Winkler to support artists in the implementation of “visionary projects.” Over the last 50 years, the foundation has grown to operate nine sites, including the renowned land art works Spiral Jetty by Robert Smithson, The Lightning Field by Walter de Maria, and Sun Tunnels by Nancy Holt. Most recently, in 2023, Dia took over stewardship of Cameron Rowland’s Depreciation, a conceptual piece that consists of an acre of land on the former site of a plantation and was given to and then retracted from formerly enslaved people as part of General William Tecumseh Sherman’s Special Field Order No.15, commonly known as the forty acres and a mule policy. As part of the piece, the land is restricted so that it cannot be developed, bringing its property value to $0, a commentary on the concept that the value of land is rooted in its use. Additionally, unlike most large-scale land art pieces, Depreciation cannot be visited.

This October, Dia Beacon opened an exhibition by Rowland titled Properties, that builds on ideas in Depreciation, and simultaneously forces the institution to reckon with the history of its property. The show consists of six components, the first of which is an unmarked acre of land in Beacon. Like Depreciation, Plot is not intended to be visited and requires that Dia, and any future owners, not “disturb or develop” the piece of property. In the section of the exhibition pamphlet on this work, Rowland explains that for some period of time Black people, both free and enslaved in both the North and South, were prohibited from being buried in cemeteries. This led to the frequent occurrence of Black people being buried in unmarked, sometimes mass, graves.

Rowland then goes on to explain that the land that Dia Beacon sits on was owned by “slave owners and slave traders from 1683 until the abolition of slavery in New York in 1827.” Based on this history, the artist assumes that the land is home to unmarked graves of Black people. This idea is the impetus behind Plot, a conceptual piece that acknowledges and strives to account for the presence of Black burial sites on Dia’s property, and even more broadly pushes viewers to reconsider “the assumed absence of Black burials on sites of enslavement.”

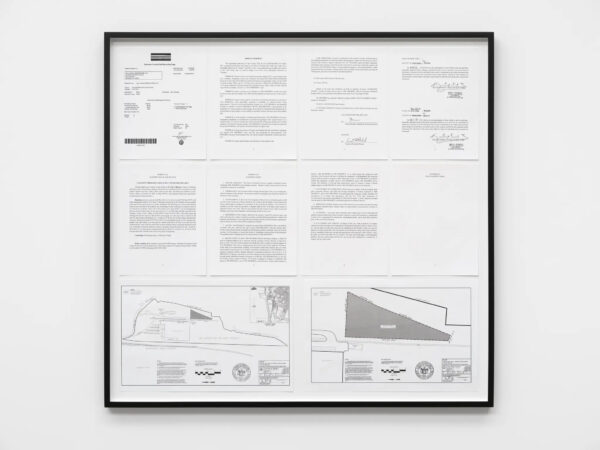

The majority of the works that make up Properties, are housed in one gallery at Dia Beacon. While a common theme throughout the curation of the institution is space — at approximately 300,000-square-feet the building easily holds large-scale pieces and provides ample space around each work —, Rowland’s gallery feels eerily empty. On the back wall, Plot is represented by framed paperwork that details the easement. To the right, Increase, a simple worn metal bedframe speaks to the history of the slave law partus sequitur ventrem, a Latin phrase that translates to “the birth follows the womb,” indicating that children born to enslaved mothers became the property of the slave owner. Across the gallery from the bed, five scythes lean against a wall. Commissary, addresses the issue of sharecropping, which is often misrepresented to deny its reality as a debt bondage, a continuation of slavery in a legal manner. Underproduction, the last piece in the gallery is a large overturned metal pot near the doorway — a reference to secret meetings or gatherings held by enslaved people.

When I first entered the space, without much context of the work, I was confused but curious about the artist’s decisions regarding objects, placement, and the amount of empty space. In retrospect, this was a narrow first impression, as Dia Beacon is filled with minimalist works that revel in empty space. Often the concept of minimalism brings to mind the simple structures and paintings of artists like Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Larry Bell, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, Josef Albers,and Robert Ryman — some of whom do have works on long-term view at Dia Beacon. However, like Rowland’s installation, other works on view a Dia Beacon play in the realm of minimalism while embodying more familiar materials and a sense of humanity.

-

- Senga Nengudi, “Water Composition III,” 1970/2018, vinyl, water, and rope; edition 1/2 + 1 AP. Dia Art Foundation

Rowland’s exhibition essay, which mostly draws on primary sources, provided the necessary context to fully understand the individual pieces in the exhibition, and perhaps sheds light on the decision to keep so much of the gallery vacant. The essay explores connections between land, labor, and value. Rowland corrects common misunderstandings related to the Emancipation Proclamation, President Lincoln’s stance on slavery, and how slavery continued under new practices, laws, and codes. The artist also details the ways in which Black people fought against “post-slavery” systems and recontextualizes Black rioting removing the notions of “race riot” to resituate these acts as “property rebellion.”

Throughout the writing, the reader is reminded that not only is land valued by its ability to be used, but that enslaved people were treated as property. Rowland writes, “Enslaved people were components of the land. The land was a prison.” The artist’s decision to make both Depreciation and Plot into pieces of land that cannot be used is echoed in Rowland’s choice to leave so much vacant space in the gallery, deconstructing our idea of value and use and, in a sense, deconstructing the prison that is the land.

Recent Comments