It is not every day that an exhibition begs, even dares, to be banned. Ban This Show, on view at Fort Works Art, does just that. It is an irreverent group exhibition taking on the hot-button issues of the day in the immediate post-election period. A chance for artists and viewers to rage, lament, and sit with the issues that remain unresolved as we enter a new political landscape.

What do you do when you feel that the world is ripping apart? Likely the only path forward is through activism. Activism is defined as “vigorous campaigning to bring about political or social change.” This is precisely what the artists on view in this exhibition are doing through their works.

There are different avenues artists take when creating activist work. One of the most common is work that spreads awareness and critiques the systems and people in power. Political cartoons, like Thomas Nast’s iconic illustration of William Tweed from 1871, are some of the most recognizable examples of this type of artistic activism shining a satirical spotlight on political figures for the public to behold.

Steven Trimble, “Poison the Well, Alice,” 2022, mixed media, spray paint and salvaged street advertisements on cradled wood panel, 36 x 36 inches

In Steven Trimble’s Poison the Well, Alice, Alice of Disney’s Alice in Wonderland dons a crimson dress with a white apron and black hair bow. While Alice retains the sweet, serene expression befitting of a happy Disney narrative, she holds up a bottle of poison for us to behold. Her shimmering, blue eyes are fixed on the bottle labeled with skull and bones. What is she planning to do with this dangerous potion? The title, suggests, that Alice may poison the well to the delight of her followers as noted by the Instagram comment and like icons at the top right of the painting. What I love about this work is its light-hearted acknowledgment of the frustration that many feel in the United States. The disillusionment with politics and other institutions is palpable. Some rejoice about the disruption a new administration will bring, others understandably have intense fear. Trimble’s work speaks to the moment in a way that captures the absurdity, especially as it plays out in the current media landscape. Do we need to destroy the well, destroy it all? Or has it already been poisoned and destroyed?

Swoon, “George,” 2016, linoleum block print on Mylar with coffee stain and hand-painted acrylic gouache, 69 x 34 inches

Another important role that art can play in the realm of activism is the promotion of empathy for others. The 1787 medallion by Josiah Wedgwood Am I Not a Man and a Brother? intended to inspire empathy for the plight of enslaved Africans. While many of the works in Ban This Show are intentionally provocative, others rely on empathy to further their cause. In this category, I would place Swoon’s George. In this monumental print, a golden, young man stands with hands clasped looking warmly down at the viewer. Beautiful patterns of reds and pinks radiate out around his body, reminiscent of a halo. Swoon, a street artist from New York, met George during a community art project and bonded with him over their shared experience of having a parent struggling with substance abuse. George serves as a representation of the compassion and empathy that promotes true healing — something we need in the United States right now as political divisions are so tense that we have stopped hearing and seeing each other.

Pussy Riot, “God Save Abortion,” 2023, short film by Nadya Tolokonnikova based on the footage of an action in Indianapolis on November 14, 2023 and Misha Waks, “Vagina (Cycle),” 2019, watercolors

Activist art also serves the important function of documenting conflict and tension. The photographs of Ernest Withers and James “Spider” Martin during the civil rights movements of the 1960s have shaped much of the collective memory of those efforts. A notable element of Ban This Show is that it has works by widely acclaimed artists like Guerrilla Girls and Pussy Riot. Immediately upon entering the gallery, viewers will be captivated by God Save Abortion, a 2023 film documenting a performance art action staged at the Indiana State Capitol. The action and the resulting film document the highly fraught battle for reproductive rights following the Dobbs decision.

I find it fascinating that the film is flanked by Misha Waks’ Vagina (Cycle) watercolor series from 2019, as the works are so abstract whereas the film is a concrete display of activism and protest. This contrast highlights the abstract ideas that many wish to hold on reproductive rights, by design. It is much easier to pass blanket laws restricting the rights of women. It is much harder when one is forced to consider the real, lived stories of women in need of reproductive health care. The works feel confrontational in that they force us to view vaginas up-close that might feel jarring to some viewers. Yet, they are also benign, subdued studies that reflect the daily experience of life continuing on for women despite massively impactful conversations happening at state capitols and courthouses.

It is important to take a moment to discuss activism versus shock value. There will be some viewers that will find the content in this show shocking, jarring, controversial, or offensive. Where is the line? When does art shock in a productive way; a way that promotes conversation and reflection? When does it simply shock for the sake of attention? Does it really matter what side of the line an artwork falls on? I do not have a tidy answer for these questions. I believe it is a matter of personal taste. I judge the success of an artwork with the stated aim of activism based on the following criteria: Does it help shine a light on an important cause? Does it have a clear message? Does it foster engagement with the issue in a unique way?

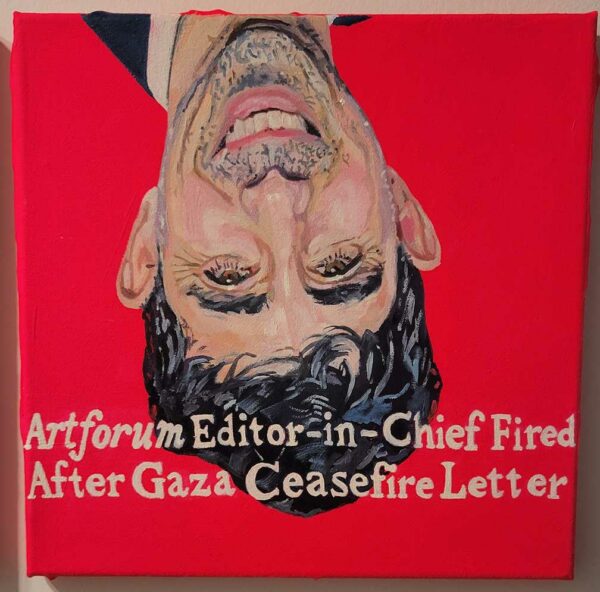

Ryan Sandison Montgomery, “What’s Art For? Must Be Pretty Pictures (Portrait of David Velasco),” 2023, oil and acrylic on canvas, 12 x 12 inches

The challenge for me with this exhibition was that it did not have explanatory wall labels. So, viewers be warned that you may walk away confused and uncertain of what you are looking at and the reasoning behind the works. In some cases, the content and message is clear. For example, Ryan Sandison Montgomery’s What’s Art For? Must Be Pretty Pictures (Portrait of David Velasco) is a critique of Velasco’s termination from Artforum following the publication of a letter calling for a ceasefire in Gaza.

On the other hand, Angel Baby by Carlos Donjuan is deserving of more context. This is a striking, large gray-toned portrait of a seated young girl wearing a dress with lace frills. However, the girl’s face distorts the image. Two metal clasps extending from a triangular form replace her eyes and nose. Two white circles, similar to clown make-up, stand in for cheeks. The mouth is only a narrow opening, like a coin slot on a washer. Without explanatory text, viewers may walk on without truly appreciating the artist’s message. The girl’s strange form is meant to challenge the strange term “alien” that we apply to those who are undocumented within the United States. Donjuan, a Dallas-based artist with personal connections to unauthorized immigration, wants viewers to contend with their own perceptions of immigrants. It is a poignant approach to helping others see the masks that so many immigrants wear as they seek to assimilate into new communities without losing their own identities, particularly when so much hostility is projected toward them and their cultures of origin.

Ultimately, Ban This Show is an important contribution to the North Texas art scene this fall, bringing widely recognized names together with local artists in an effort of highlighting significant issues. With such a diverse selection of artists, this group exhibition offers a lot for viewers to take in. My remaining question is how future generations will view this moment and how works like these will help shape those memories. The history of this unnerving moment is yet to be written. Thus, it is necessary for the activism to continue. I am grateful to the artists of this exhibition for carrying on this work.

Ban This Show is on view at Fort Works Art through December 7, 2024.

Recent Comments