It is possible that the infrastructure a particular culture develops and utilizes in unseen ways can provide a different kind of mapping, one that describes personal interactions and taboos, rather than septic routes and strategically positioned manhole covers. Ariel Wood adopts such a strategy in their new exhibition, rest, raze, cullect, which is now up at Lawndale Art Center through December 21st.

This remarkable show combines three distinct, yet interrelated, bodies of work all focused around a particular “infrastructural situ.” The most subtle, yet perhaps most alluring of the collection are the prints, composed of hard ground etching and aquatint on Hahnemuhle copperplate. The resulting images are a masterful exercise in tone manipulation. They present vistas of quotidian infrastructural conditions. They are unassuming and draw the viewer in, and the longer they are viewed, the better the payoff in that one’s eye takes time to adjust to the gentle transitions of grey. They are quite poetic on their own.

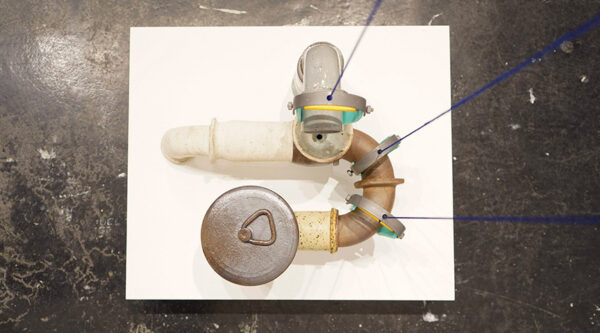

These 2D prints are joined with other objects made from a variety of materials. In weave, 2b (face), Wood presents wonderfully realized plumbing infrastructure rendered in glazed ceramic, which is “suspended” from long, blue strings that draw up to the ceiling in a smart nod to the existing gallery architecture. The sculptures rest on small plinths, so they are not suspended. The careful, unique hanging apparatuses, all fabricated by Wood, make the presentation feel designed for utility, yet are purely aesthetic. These objects interact with one another in the way that plumbing or drainage lines do, each having its own logic and utility, yet are void of that original function.

This provides Wood with an opportunity to create a unique take on their municipal reinventions. From the artist’s statement, Wood claims, “I inhabit this formal lexicon to speak to an underlying interconnectedness and a celebration of queerness.” The idea is that the medium of infrastructure, here rendered non-functional or primarily aesthetic, creates a door for the artist to overlay other societal happenings that are tangentially related, such as bathroom gender allocations or other trans concerns. The show retains a freshness that surpasses other similar strategies in that the craft and detail are so lovingly rendered, the artist’s respect for their adopted language is paramount. In other words, the concept of transgression is an essential ingredient, but the show hits on all levels so that it is universal to all who view it, no matter their relationship to trans issues.

Wood shows us that we take for granted the “way things are” and we hardly ever think of something like plumbing infrastructure until we have a problem with it. Then it is universally a problem. A similar light is shone on the issue of trans rights, enlightening us that these issues are societal — all of our concerns. This is done through Wood’s careful presentation of a show that speaks a universal language through excellent execution.

Recent Comments