The threads of generational memory and cultural resilience weave powerfully through De Generación En Generación, reminding us how art preserves the stories of communities over time.

The exhibit, co-curated by Dr. Rote and Dr. Liz Kim, opens with Antonio E. García, whose work predates the Chicano Movement. He was born in 1901 in Monterrey, Mexico, and in 1914, the artist immigrated with his siblings to San Diego, Texas. After studying at the Art Institute of Chicago from 1927 to 1930, he returned to South Texas, moving with his family to Corpus Christi, Texas in 1935.

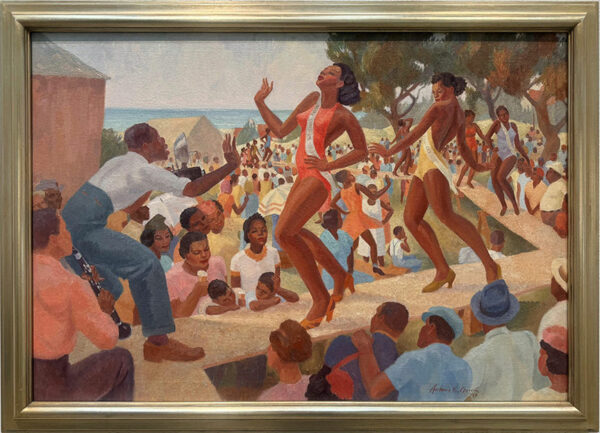

Antonio E. García, “Juneteenth Review,” 1949, oil on canvas, 33.5 x 44.5 inches. Courtesy of the Collection of the Art Museum of South Texas

García’s Juneteenth Review captures the energy of a June 19, 1939, celebration at South Bluff Park in Corpus Christi. Black women in swimsuits jubilantly strut on stage toward a cameraman, as a clarinet player serenades the festivity, surrounded by an attentive audience. Juneteenth is a holiday of Texan origin, which began on June 19, 1865, when enslaved Texans learned of their freedom; the holiday is now celebrated nationwide.

American Regionalism came to light around 1930; it is an art style that is figurative and narrative, returning back to an ideal of art-as-storytelling. García acknowledges an early celebration of Juneteenth with his signature regionalist aesthetic, which includes a muted color palette and stylized faces that favor portraying the cultural significance of the moment over realism.

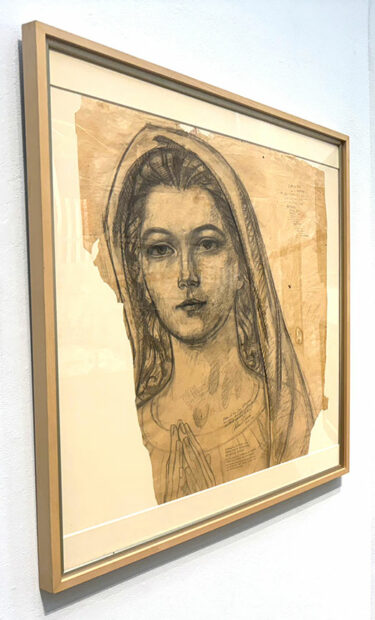

Antonio E. García, “Virgin (for fresco at the Corpus Christi Seminary),” ca. 1950, graphite on vellum, 34.25 x 33.5 inches. Courtesy of the Collection of the Art Museum of South Texas

García’s aesthetic often recalls religious subjects, such as his portrait of the Virgin Mary. Though depicting a religious entity, the artwork is grounded in the artist’s personal life; the woman who posed for the artwork is his wife, Herminia García. Only a small fraction of the fresco remains, which is displayed to scale.

Amado Peña, Jr., “Aquellos que han muerto,” 1975, serigraph, edition 14/20, 16 x 10 inches. Courtesy of Peña Studios, Inc., Santa Fe

Amado Peña Jr’s included artwork represents a shift from the regional South Texas aesthetic of Garcia’s artwork to a more politically inclined printmaking style that focuses on Chicano issues. For example, Peña’s Aquellos que han muerto (Those who have died), from the artist’s “blood and guts phase,” calls attention to the 1973 murder of twelve-year-old Santos Rodriguez. The young boy was killed by police over allegations of robbing $8 from a vending machine at a gas station near his home in Dallas, Texas. In the print, Peña encapsulates Rodriguez’s vibrant smile, starkly contrasted by the blood streaming down the right side of his face.

The names of other Latino boys and men who died as a result of police brutality juxtapose the multiple colors of Rodriguez’s shirt. Alfonso Flores, for instance, was getting a haircut on February 6, 1971, in Pharr, Texas, when violence erupted outside due to protests against police violence. Flores stepped outside the barbershop out of curiosity and was shot and killed by Deputy Sheriff Robert C. Johnson, who was found not guilty of murder.

Peña’s Aquellos que han muerto exposes the pattern of police violence against young Chicanos in south Texas communities. The artist uses Rodriguez as the “poster child,” who is merely one of the numerous male youths whose lives were cut short, hence the multiple skulls in the background. The artwork confronts viewers with the brutal realities of systemic violence, serving as both a tribute to lost lives and a call for justice, embodying the activist spirit of the Chicano Movement.

Gina Gwen Palacios, “Seeds of Labor,” 2024, wood, burlap, lace, window screen, rattle snack rattle, vegetable box, religious card, cotton seed, cotton, rosary, and American Flag, 152 x 109 x 121 inches. Courtesy of Jennifer Arnold

Finally, we arrive at Gina Palacios, who reflects on deeply personal narratives of labor and identity in her artwork. Palacios represents the current generation of Chicano/a artists in the twenty-first century. One of the most visually striking artworks to me was the artist’s installation, Seeds of Labor, which made its debut with this exhibition. The installation is brimming with symbolism; at its foundation lies cotton seeds and picked cotton on top of the seeds. Standing above the foundation is a wood frame house, which contains table runners, a net with a rattle from a rattlesnake, a vegetable box, cloth, cotton plants, and a rosary made from cotton seeds. An American flag hangs between the house frame’s body and roof.

The artist’s parents were cotton pickers in Taft, Texas. The dangers of rattlesnakes were a constant reality—symbolized by the netting with the rattle in the installation. Their Catholic faith sustained them through the hardships of agricultural labor. The house Palacios constructs embodies her family’s American story, with its framework rooted in the cotton that flourishes in the South Texas climate. The tactile, layered materials in Seeds of Labor evoke both the grueling physicality of farm work and the faith required to endure such harsh conditions.

Gina Gwen Palacios, “American Primitive,” 2017, oil on canvas, 60 x 44 inches. Courtesy of Gina Gwen Palacios.

Through American Primitive, Palacios evokes the idea of the American Dream by depicting a mother, tanned from working the fields, who holds her son’s hand. The boy’s lighter skin suggests that his labor in the fields has yet to begin. The figures’ rounded faces, reminiscent of Olmec colossal heads, visually reclaim Indigenous roots, grounding the figures in a broader narrative of cultural heritage and resistance. The artist’s representation of Indigenous identity underscores a central aim of Chicano art—asserting and celebrating cultural origins in the face of historical erasure.

In the background, the flat south Texas landscape thrives, with a cotton field far out in the distance. A large sky looms above. The artist not only recalls her own family but also honors others whose tireless labor in fields at the U.S.-Mexico border often goes unrecognized.

Each of the three artists creates art that speaks to their American stories, shaped by their families and South Texas communities. Where García’s regionalism documents historical milestones, Peña transforms these narratives into calls for justice, paving the way for Palacios’ explorations of cotton picking. This exhibition not only showcases three remarkable artists but also effectively demonstrates how art preserves and reshapes the Chicano/a experience, encouraging reflection on the ties between history, community, and identity.

Driving back to San Antonio, I found myself seeing the fields that stretched along the way in a different light—imbued with the histories, stories, and resilience captured by García, Peña, and Palacios. Jennifer Arnold, Assistant Professor of Art and Director of University Galleries at TAMUCC, states that “the Weil Gallery is honored to debut this exhibition and we invite the public to come learn and travel through the generations with us until February 1, 2025.”

De Generación En Generación: Three Generations of South Texas Chicano/a Artists is on view at the Weil Gallery at Texas A&M University – Corpus Christi until February 1, 2025.

Recent Comments